DJI has failed to overturn the U.S. Department of Defense’s decision to label the drone maker a Chinese military company, with a federal judge upholding the designations and ruling that DoD has plenty of reasons for putting the company back on its blacklist. The ruling leaves a label with considerable reputational and commercial consequences on the world’s leading civilian drone brand.

In a voluminous opinion, Judge Paul L. Friedman of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia ruled that the Defense Department had introduced “substantial evidence” that DJI’s products and technologies are being used to surveil Muslim populations in China and may be doing so elsewhere in Asia, contributing to its military research programs. While the court axed a number of the government’s secondary rationales, it found that the core case — that DJI manufactures products with civilian and military capabilities and that its products can be employed on the battlefield — was strong enough to support the listing.

What the Court’s Ruling Says About DJI’s Status

The court treated the dispute as an administrative law challenge and used a deferential standard to its ruling on the Pentagon’s determination. DJI said that it was not a defense contractor but rather a consumer and commercial manufacturer, pointing to company policies prohibiting use by the military. Judge Friedman deemed those policies inadequate to offset the facts that DJI’s off-the-shelf drones can be — and have been, as is routine — modified for military use.

Most important, the judge said, the Defense Department did not have to prove that the People’s Liberation Army owned or controlled C.M.C.C. in order to justify its designation. Instead, it was required to have a cogent basis that demonstrated real contribution to China’s defense ecosystem. The court also indicated that some of the government’s more speculative claims found no basis in the record, narrowing but not dismissing the agency’s position.

Evidence of DJI Drones Used on the Battlefield

The decision was based on a steady stream of reports in open-source reporting, assessments by the government and other sources that studied the use of modified DJI products in conflict zones. “The best analogy is that this is like providing equipment to collect intelligence,” said one individual with knowledge about the matter. “If we are even uncertain if information collected could directly or indirectly cause harm to members of a population, then isn’t it better not to provide any support?” he asked when informed about China’s growing market share.

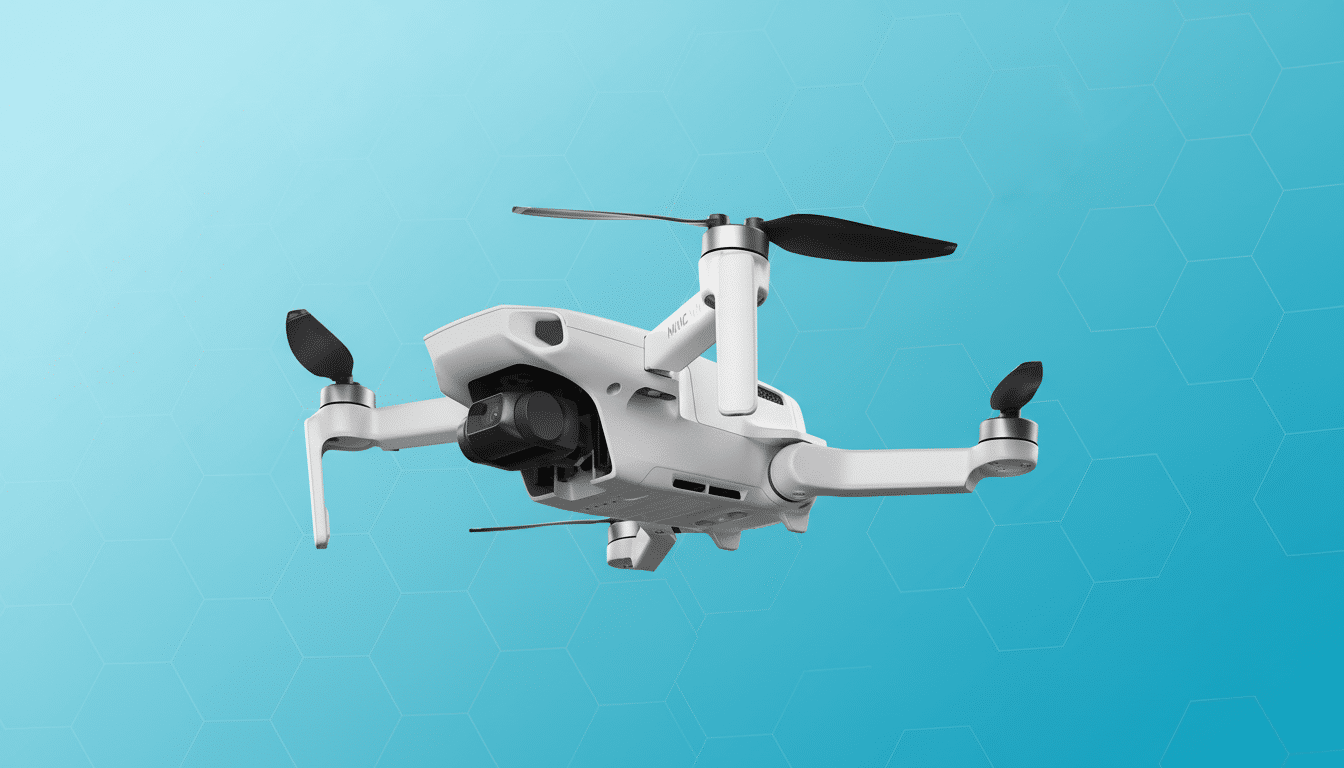

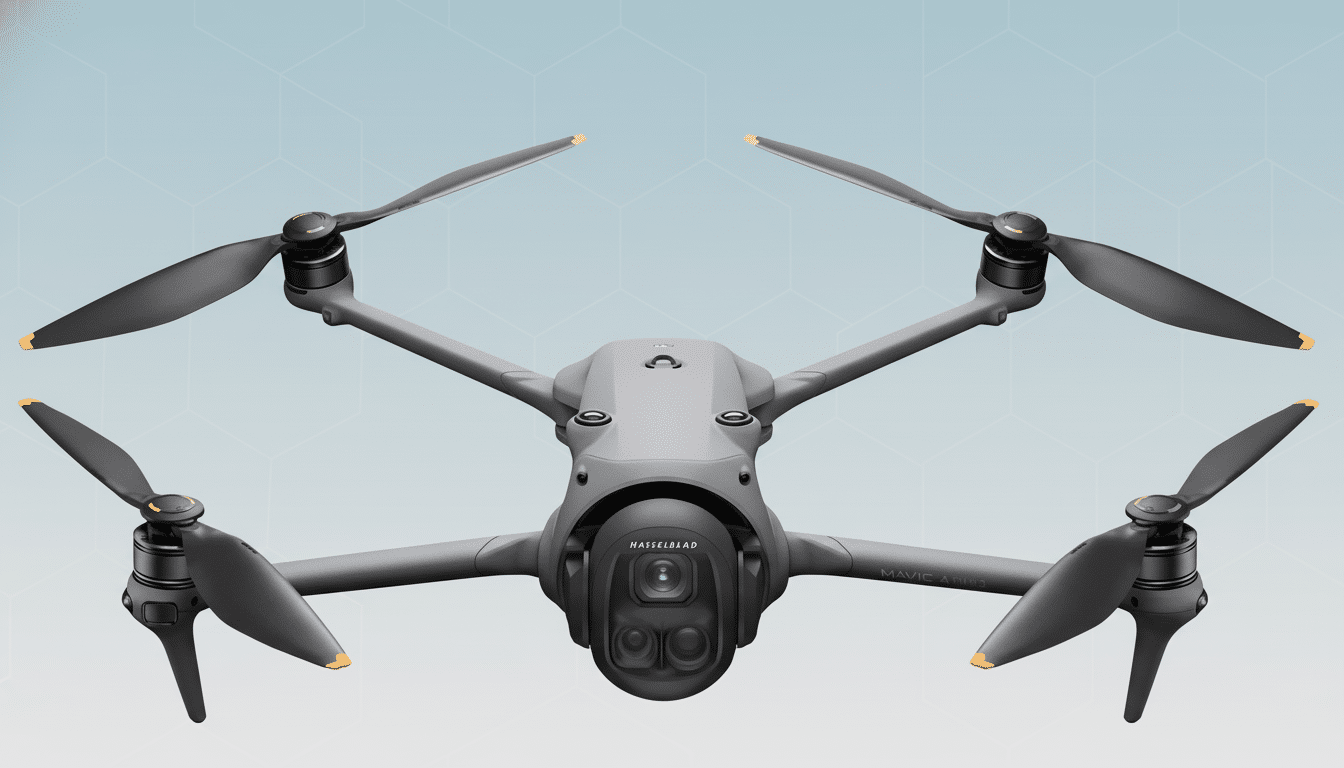

Research by organizations such as the Royal United Services Institute and Conflict Armament Research has documented use of DJI’s commercial Mavic and Matrice models for surveillance, artillery spotting, and improvised munitions drops on both sides of the front line.

Per the court summary, DJI’s efforts to dissuade military use through terms of service or geofencing did not outweigh the observable reality of how hardware behaves in the wild. On the battlefield, users have routinely found ways to overrule software restrictions and swap out parts, while using drones’ payload capacity — or even their video-link feeds — for tactical advantage: classic signs of dual-use tech.

Why the Pentagon’s Military Label for DJI Matters

Staying on the Pentagon’s list of Chinese Military Companies also piles onto existing U.S. policy headwinds for the company. DJI has already been subjected to export restrictions by the Commerce Department and a Treasury designation that restricts some American investments. The combined actions make it challenging to finance, form partnerships and plan supply chains around U.S.-touching deals, yet do not add up to a blanket ban on private ownership or use.

Public-sector procurement is particularly sensitive. Federal agencies and a growing list of states and localities have already enacted rules that guide buyers toward such so-called NDAA-compliant platforms or the Defense Innovation Unit’s Blue UAS roster. Public safety agencies that receive federal grants steer clear of DJI to make compliance simpler, a trend the company has referenced in court filings as having contributed to financial and reputational damage.

Market Impact and Wider Industry Context for DJI

DJI controls about 70 percent of the world’s small-drone market, according to analysts at Drone Industry Insights; the firm also tops categories such as consumer and enterprise drones for inspection and mapping. According to surveys conducted by DRONERESPONDERS, a public safety nonprofit, a majority of U.S. first responder programs either use or used DJI aircraft.

Policy constraints created space for alternatives. But American and allied suppliers, including Skydio, Teal Drones and Parrot, have beefed up offerings that would comply with federal sourcing and cybersecurity requirements. Unit costs are higher and feature lists are shorter, procurement officers will tell you, when compared with mass-market DJI models. And the ruling is apt to reinforce this bifurcation: DJI will continue to dominate among private commercial users, while government purchasers move increasingly toward vetted platforms.

What Comes Next for DJI After the Court’s Ruling

DJI has the option to appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, but the deferential standards that apply to agency listings will make it hard to succeed. Meanwhile, the company can keep trying to deflate security concerns and mitigate risks by lobbying and technical outreach to regulators, arguing that design changes cut back those risks.

For U.S. investors and distributors, the first lesson is business as usual: due diligence will continue to be complicated, and contracts associated with federal funds must remain conservative. The ruling carries broad implications for policymakers: the principle that dual-use performance and actual battlefield use trump corporate disclaimers about intended use may now be applied in determining when emerging tech firms can and cannot be trusted if their products straddle consumer and defense domains.