Google is in the process of buying 200,000 metric tons of carbon removal credits from Mombak, a Brazilian company that is reviving native forests on deforested farmland in the Amazon. The deal, brokered through the Symbiosis Coalition for transforming industrial systems, shows how big tech companies are increasingly turning to nature-based carbon removal alongside high-tech methods such as direct air capture.

The amount is significant: 200,000 tons of carbon removal is about equal to taking more than 40,000 passenger vehicles off the road for a year, according to U.S. EPA estimates. But the signal may be even more important than the tonnage. By supporting a reforestation developer at such scale, Google is wagering that well-vetted forest projects can deliver genuine climate benefit — along with biodiversity and water improvements — in ways industrial solutions cannot.

Inside the Deal and the Players Behind This Purchase

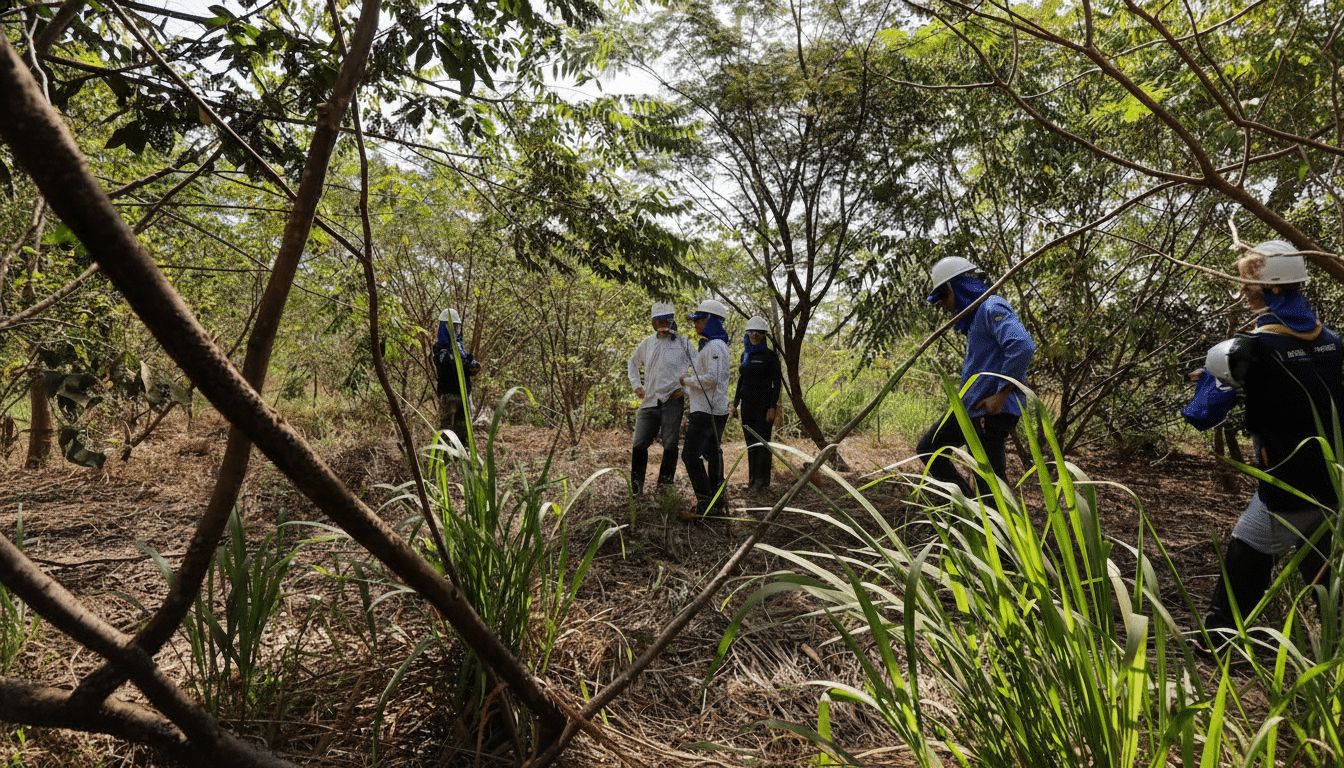

Mombak’s approach is simple in principle but difficult to pull off: buy up degraded agricultural lands in the Amazon, replant a mix of native trees, and then manage those forests for decades as they store carbon and help regrow ecosystems. The credits are generated as the new forest grows, using third-party protocols for afforestation and reforestation, and tracked over time to make sure that carbon remains locked away.

The Symbiosis Coalition, which negotiated the deal, is an advance market commitment financed by Google with McKinsey, Meta (the parent company of Facebook), Microsoft, and Salesforce. Its goal is to create an investment pipeline of high-integrity nature-based removal by supplying the future demand for it — a similar strategy to Frontier’s close to $1 billion commitment in engineered carbon removal. Where Frontier focuses more on technologies like direct air capture and mineralization, Symbiosis is putting its emphasis on living systems that can scale quickly and deliver co-benefits.

The purchase fits into Google’s broader climate goals, which include a commitment to run on 24/7 carbon-free energy by 2030 and to slash its value chain emissions.

The company said it will use DeepMind’s PerchAI to assist with the measurement of biodiversity outcomes, using AI on acoustic data, imagery, and field observations to monitor species richness and habitat recovery.

Why Nature-Based Removal Still Splits Experts

Nature-based credits are potent but subject to scrutiny. The permanence of carbon storage can be compromised by fire, pests, and drought. Additionality and leakage need to be demonstrable: would the forest have come back anyway, and does protecting one place just lead to acres lost somewhere else? Initiatives like the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market’s Core Carbon Principles and the Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative’s claims guidance are moving the market toward more robust baselines, monitoring, and disclosure to deal with exactly these concerns.

Projects of high enough quality are increasingly adopting multi-decade contracts, conservative baselines, and “buffer pools” that insure the carbon stock against unexpected losses. AI and remote sensing enhance measurement, reporting, and verification, while durable on-the-ground strides are shored up by investments in fire management and long-term stewardship funds. Of course, these safeguards do not completely mitigate risk — but with rigorous implementation, they can lower it to levels more in line with other types of removal.

Crucially, forests provide benefits that engineered solutions do not. Returned Amazonian landscapes can replenish aquifers, stabilize soils, establish wildlife corridors, and provide local livelihoods. The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report identifies reforestation and ecosystem restoration as this decade’s gigaton-scale mitigation options — but they must be high integrity and respect social safeguards.

Scale and Impact in the Amazon from Reforestation

A linchpin of global climate stability is still Brazil’s Amazon. Data from Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE) indicate that the pressure has eased in recent years following a decade of high loss, but the restoration backlog is immense. Converting exhausted cattle pasture back to its original state as native forest can sequester carbon for decades while also stitching together fractured habitats that are critical for species survival.

Mombak’s method — bringing back native polycultures, not monoculture plantations — is meant to more closely replicate the Amazon’s ecological complexity. That is important for carbon, and it’s also important for resilience: multi-species forests tend to capture and store more carbon over the long haul, and are generally better able to resist droughts and diseases. If buyers like Symbiosis and others can offer reliable, multi-year demand, developers will be able to design at landscape scale for investment that matches the long timelines needed by forests.

What to Watch Next for This Restoration Effort

Transparency will be key. Investors and watchdogs will be on the lookout for public details around methodologies, monitoring intervals, and how risks are priced and insured for permanence. They will also examine how the credits are used in corporate claims. The initiative’s Net Zero Standard encourages companies to focus on those absolute reductions, and use removals to counter any remaining emissions — a best practice that is rapidly emerging.

Oh, what a beautiful market signal it is: businesses are developing mixed portfolios of carbon removal — durable, engineered pathways, and near-term biological sinks. If Google’s purchase makes it easier to de-risk high-integrity restoration at scale, it could help catalyze a wave of projects across the Amazon basin — driving real climate benefit, biodiversity recovery, and water security in a part of the world that the planet needs to deliver all three.