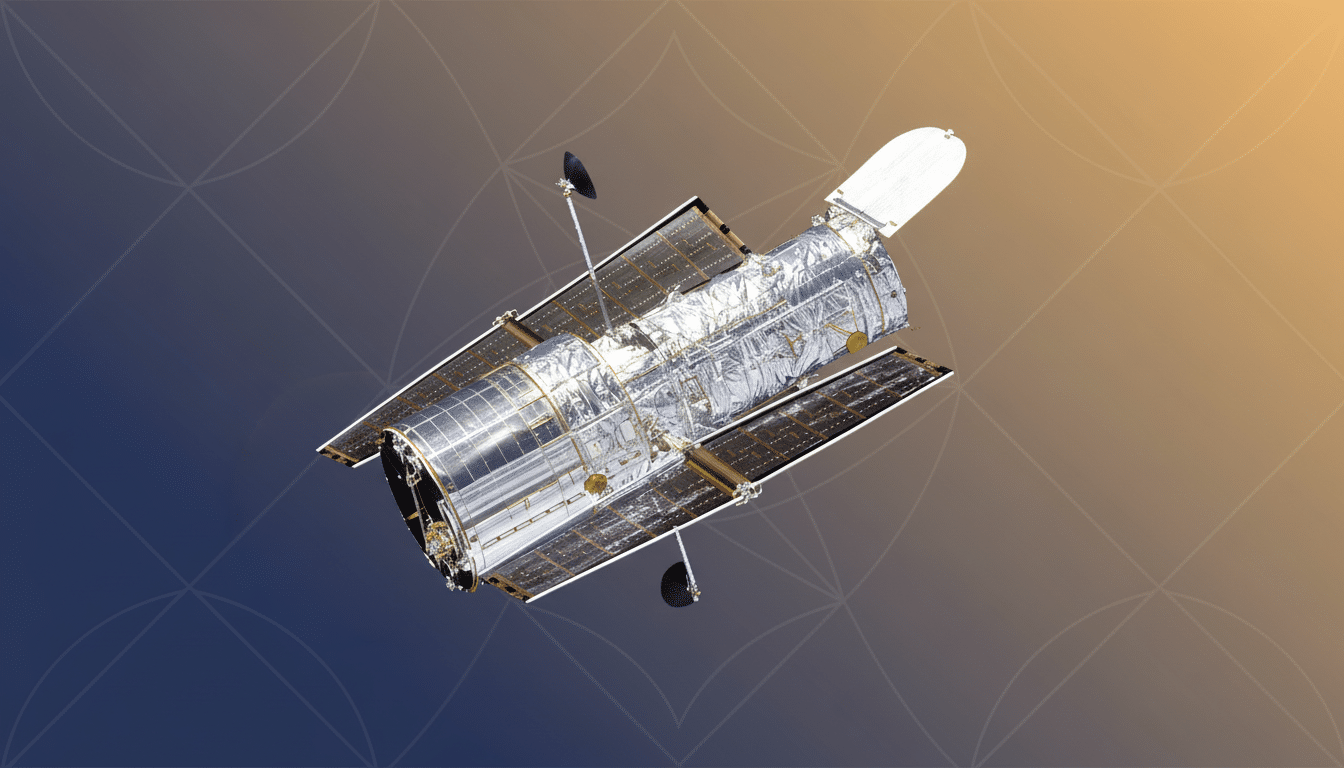

NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has taken the first visible light photo of a pair of back-to-back planetary smashups in the debris belt around Fomalhaut, giving stargazers a mobile trip for our future Milky Way–held solar system.

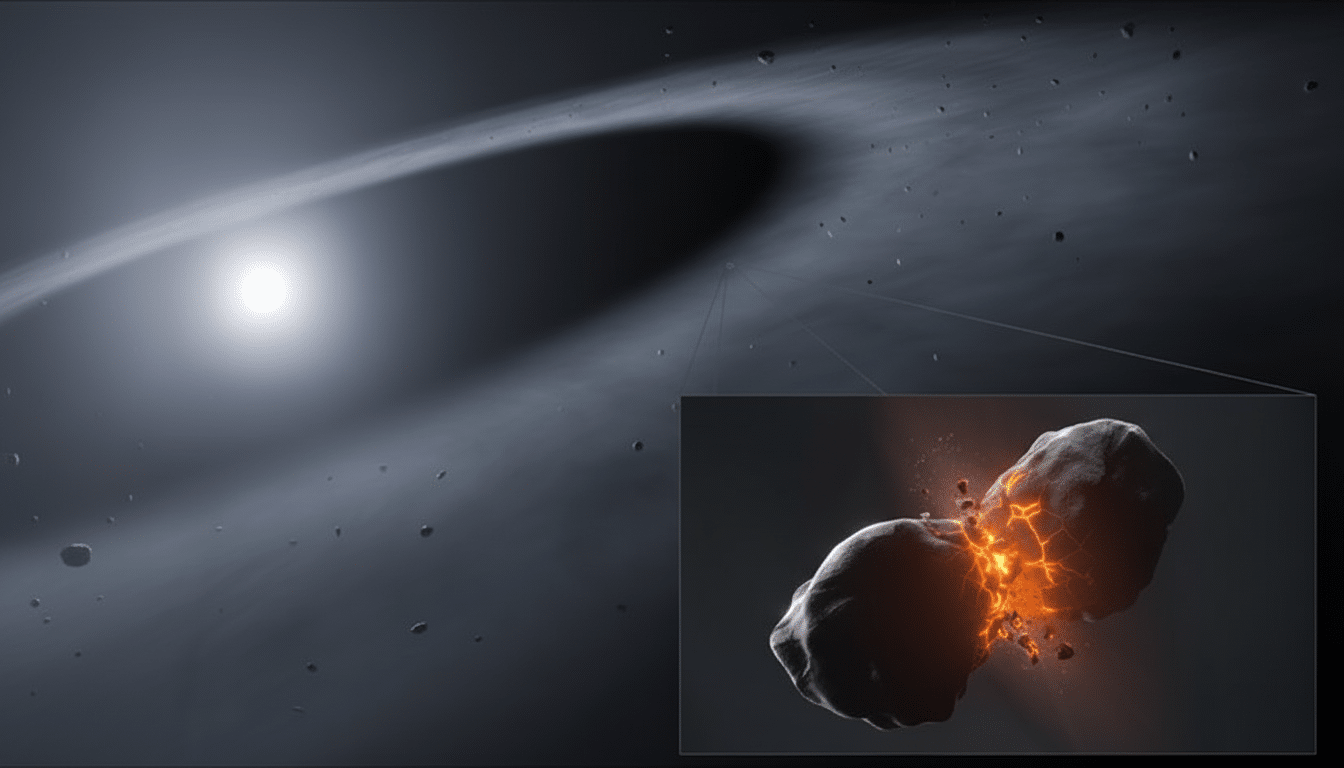

Astronomers announce the detection of yet another point source of reflected light that arose from near the inner edge of Fomalhaut’s main dust ring — alarmingly reminiscent of a mysterious object imaged in the mid-2000s but which then faded and dissipated. Taken together, the detections suggest that violent crashes between big planetesimals — the rocky building blocks of young planets — are occurring inside an established planetary system.

A Nearby Crash Laboratory for Planet Formation

Fomalhaut, a well-known A-type star in the Southern Fish constellation, has been held up for years as evidence of debris disks — as wide belts of dust and ice that resemble the disk-shaped Kuiper Belt far beyond Neptune. The star’s large outer ring — shaped in part by hidden gravimetric forces — is a natural lab in which to watch the physics of planet formation unfold. Hubble’s coronagraph, which shields starlight to reveal faint structures, has mapped arcs, clumps and luminous knots in the disk that betray recent hits.

In the most recent observations, scientists observed a faint source near the inner edge of this ring. Its location matches the region astronomers anticipate would be home to high-speed traffic of kilometer-sized bodies, in which collisions grind large and big objects into clouds of fine dust that temporarily brighten in starlight.

The Planet That Wasn’t: Fomalhaut b Reconsidered

Twenty years ago, Hubble snapped a picture of a tight point source — affectionately named Fomalhaut b — and the world heard about it. It was celebrated as the first exoplanet ever observed in visible light. But rather than holding steady as a planetlike dot, the object dimmed and then elongated and disappeared. That behavior is consistent with a debris cloud spreading out and thinning in the face of the star’s inward-directed radiation pressure, not a stable world orbiting placidly nearby.

The fresh detection, located in approximately the same region of the ring, bolsters the argument that its predecessor “planet” was an afterglow from a collision.

A group led by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, along with scientists in the United Kingdom and elsewhere, describes the findings in Science and says Fomalhaut’s disk is undergoing a rash of large impacts, not a single one.

What the Dust Is Saying about Fomalhaut’s Collisions

These temporary points of light gleam by reflecting starlight off fresh, micron-sized dust grains. In a system such as Fomalhaut’s, the star’s powerful light quickly blasts the smallest grains outward and causes the cloud to expand and dim over time. That neatly accounts for why the original paled away and why the newcomer will follow suit.

According to the brightness of the collision and how widely it spread, researchers believe the colliding bodies were somewhere around 60 kilometers across — larger than most of the asteroids that are thought to be shattered by smashes in our own solar system. These slams are fire-and-forget, introducing generous quantities of dust and starting what’s known as a “collisional cascade” that is remaking the disk’s architecture. From the size distribution, reflectivity and how rapidly the fragments disperse, astronomers can infer whether these planetesimals were icy or rocky, or perhaps constituted a layered mix.

The system is the equivalent of a materials lab in space: by observing clouds brighten and then puff out, astronomers can deduce grain sizes, ice content, and the mechanical strength of the parent bodies — important parameters for models of how small debris clumps into planets and occasionally falls to pieces catastrophically.

A Collision Rate That Is Above What You’d Expect

To observe two major impacts within the same orbital zone and from nearly the same point of view is astounding. Simple models predict that the catastrophic collisions of objects tens of kilometers across should be very rare — a once-every-100,000-years kind of event for each individual location. The return visit to the vicinity of Fomalhaut’s ring reveals local dynamical excitation, conceivably due to gravitationally focusing potential planet-mass particles into reducing orbits and onto collision courses.

If confirmed, this would put further constraints on the masses and orbits of hypothetical planets shepherding the ring’s sharp edges and out-of-round shape. It also recasts the duration for which old systems can continue to be collisionally subluminous, indicating that late-stage grinding can proceed for much longer after the epoch of terrestrial planet assembly.

Next in Line for Webb and Hubble Observations of Fomalhaut

Hubble will observe the bright spot’s changes, timing its expansion and fading. The James Webb Space Telescope can fill in the gaps left between such snapshots and peer into that same dust in infrared light, which reveals both temperatures as well as spectral fingerprints that indicate composition — silicates, water ice, or organics — and also grain size. NASA and ESA observatories combined provide a kind of triangulation of the dust mass, particle spectrum, and energy in the impact.

Beyond the headlines, the flickers of Fomalhaut furnish a time-lapse glimpse of planet building by attrition and accident. They bear out a humbling fact: in systems long past their birth convulsions, new worlds can still collide, illuminating the dark with brief but instructive sparks.