NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has peered nearly 400 million miles farther into space than existing observations of an especially large planet-forming disk, and in doing so has set a new record for the most enormous-yet protoplanetary disk.

The object, known as IRAS 23077+6707 and about 1,000 light-years away, is a dense silhouette that looks like a hamburger with bright buns of scattered starlight above and below — the perfect textbook picture for understanding how new worlds are made.

A Gargantuan Disk, With Space for Giants

The disk is so wide, the team of astronomers who conducted the study, which was published in The Astrophysical Journal, says it “dwarfs any planetary system ever observed with Hubble,” about four dozen times as large as our own neighborhood of planets, out to the Kuiper Belt.

Modeling estimates that 10 to 30 Jupiter masses of material still remain in the dusty reservoir, enough raw material to make multiple gas giants and a menagerie of smaller worlds.

The research team, which also includes Kristina Monsch and others from the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, dubbed the target “Dracula’s Chivito” in reference to the respective heritage — Transylvania and Uruguay — of some collaborators, as well as to how stacked it appears.

Whimsy aside, the disk is so large and clear that it serves as a natural laboratory for testing theories of how planets form.

Why the Edge-On View Is Game-Changing for Planet Studies

An edge-on disk is scientifically good to observe. This foggy midplane behaves much the same way as a hand to a light bulb — obscuring the glare of the central star, or a pair of stars — and allowing for only faint outlines to be seen among such heady stellar company. Through Hubble’s lens, the scene is cleaved down the middle by a dark lane of vividly cosmic dust, with bright, fan-shaped reflections above and below where starlight ricochets off tiny motes.

This geometry allows scientists to look directly between the disk’s vertical layers — at how dust of different sizes stacks up, at how turbulence stirs the mix, and where grains may grow from smoke-like motes into pebble-sized LEGO bricks.

Those layers are important: They establish the initial conditions to form planet cores and determine whether a system will end up dominated by rocky super-Earths, mini-Neptunes, or Jupiter-scale giants.

Signs of Chaos in a Mature Planetary Nursery

Despite evidence of a rather mature system, with no powerful jets seen blasting away (a signature feature of very young, mass-slurping disks), the structure is anything but calm.

Hubble spots wisps and filamentary structures while observing the central region of the Milky Way galaxy. The overall brightness and morphology vary with wavelength, which confirms the presence of grain-size stratification.

This asymmetry suggests something active and ongoing: perhaps local clumps where giant planets might someday form, vortices that trap dust, or gravitational nudging from a still-unseen partner.

As Monsch and his colleagues point out, the view is that planet nurseries can stay dynamic — and not settled down even a bit — long after they undergo their first growth spurt.

How It Stacks Up vs. Other Planet Cradles

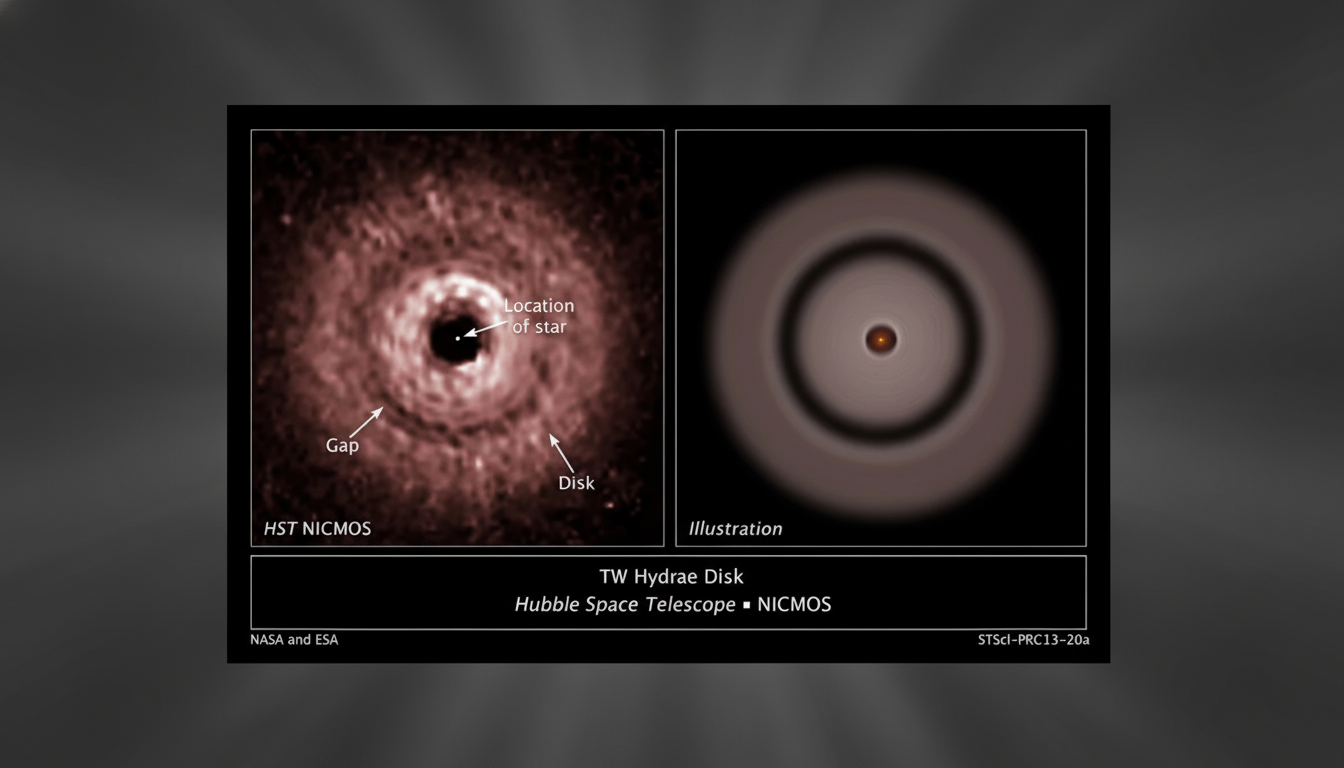

Over the past decade, facilities like ALMA and the Very Large Telescope have revealed stunning disks with rings, gaps, and spirals — HL Tauri’s concentric annuli, TW Hydrae’s sharp inner voids, PDS 70’s cavity (which is home to two newly discovered protoplanets). Hubble has also provided classic edge-on rays like HH 30 and HK Tauri. IRAS 23077+6707 is remarkable for its size as well as the prominence of vertical structure, providing a complementary view to the relatively ring-dominated perspectives from radio telescopes.

Together, these systems are rewriting the chronology of planet formation. Increasing evidence indicates that grain growth and the first stages of planet-core formation may begin rapidly even as disks continue to evolve and, here, exhibit significant asymmetries.

What Astronomers Will Look for Next in Follow-Up Observations

Follow-up with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array might be able to map colder, millimeter-scale grains and follow gas motions for hidden clumps or Keplerian deviations that would hint at forming planets.

Observations with the James Webb Space Telescope’s infrared instruments might be able to pick out signatures of organic molecules and warm dust, painting a more detailed picture of chemistry and grain growth in the disk’s surface layers.

Key questions now: Do the filaments mark infalling material, or otherwise visible planetary wakes, or magnetic mischief? Is the disk around a single star or a close pair? And how quickly will this bloated system quiet down — if it quiets at all — and fit into the neat framework that we see in mature planetary systems?

For now, Hubble has afforded scientists a rare view from the front row to the messily brilliant middle act of world-building. By catching IRAS 23077+6707 pulling itself into an extreme contortion, astronomers with NASA, ESA, and the Space Telescope Science Institute have formally opened up an abundant, data-heavy target to be used for comparison studies of planet formation for years in the future.