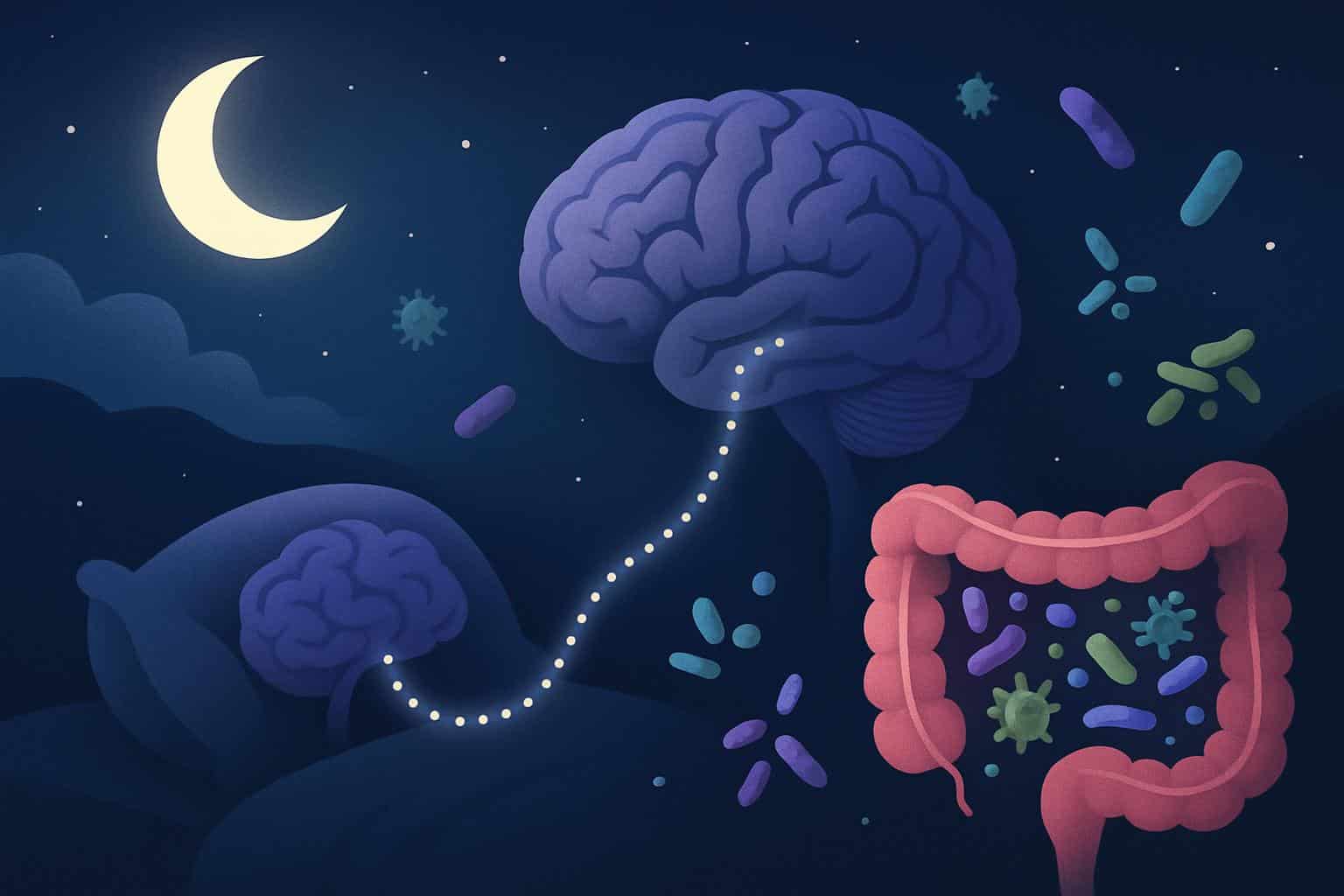

The tiniest residents of your body are busy as you drift toward sleep. Trillions of bacteria in your gut and mouth talk to your brain through molecules in your blood and through the vagus nerve, which runs from your brain stem down to your abdomen, and they send messages back again, influencing your immune system and even your mood and behavior, some studies have found — and a rapidly expanding small body of research suggests that they may also be able to help determine how well and how much you sleep.

This isn’t fringe biology. We now know that the makeup and diversity of the microbiome may be associated with how much you sleep, how well you sleep and even the time at which your internal clock says you should wake up in the morning. The results suggest new ways to address insomnia, social jetlag and obstructive sleep apnoea — beyond an amber bottle.

The gut–brain sleep corridor

For years, doctors have assumed that sleep disorders disrupted the microbiome. Many still do — but the evidence suggests it’s a two-way street. According to a number of studies, people with a medical diagnosis of insomnia have less diversity in their gut bacteria than do normal sleepers, a pattern that’s considered unhealthy and has been linked to increased risk for impaired metabolism and immune function.

In a 40-person study of healthy adults who wore sleep trackers for 1 month, those who slept fewer hours had less diverse gut communities. A further analysis showed teenagers and young adults with greater diversity of oral microbes had more hours of sleep logged. These are associations, not proof of cause — but the signal continues to emerge across various body sites.

Big swings between weekday and weekend sleep — social jetlag — also leaves a microbial fingerprint. Research has identified distinct gut profiles in people whose sleep whose sleep was disrupted by irregular sleep as opposed to those whose sleep was regular, according to data analysed by scientists at a UK health science company.

Circadian clocks connect with microbial timekeepers

Shift workers, first responders, and anyone who works or stays up late or eats too soon before bed may struggle with circadian disruption, say experts in integrative physiology. But when the clock misfires, gastrointestinal troubles and metabolic risk increase — and these are conditions where the microbiome is frequently disrupted.

Diet is one reason. Short sleepers also grab for more sugar the next day, say nutritional scientists at King’s College London. Yet diet doesn’t explain everything. In the social-jetlag group, nine species were blooming and eight were dwindling in those with irregular sleep; food choices had a partial role in the changes.

How could microbes influence sleep?

Some suspect specific bacteria nudge the brain’s sleep circuitry themselves. In work led by a neuroscience group at Nova Southeastern University, several Firmicutes taxa, one of the gut’s dominant bacterial phyla, were correlated with distinct sleep metrics in men, with some lineages associated with better sleep and others with worse.

More dramatic hints come from fecal microbiota transfer. The mice became more wakeful in their normal rest period when they were given gut microbes from people who reported jetlag or insomnia. In a separate experiment, shifting microbes from human jetlagged poop to mice was associated with weight gain and worse blood sugar control in the mice — classic ripple effects of circadian disruption.

Using these studies related to username, we have the following

Small, preliminary studies conducted on patients indicate that when the gut’s bacteria is altered by fecal transplants, insomnia symptoms decrease and stay away; however, researchers say that more rigorous randomised, double-blind trials are needed before making a conclusion about the effectiveness of the treatment.

Chemical messengers in the mix

Why should bacteria influence sleep in the first place? Chemistry. The microbiota in our gut contribute to the production or modification of neurotransmitters — gamma-aminobutyric acid, dopamine, norepinephrine, serotonin — and short-chain fatty acids such as butyrate. These ingredients might alter brain excitability, inflammation and the circadian clock that dictates when you sleep.

Human experiments add texture. In some studies, volunteers who were given particular antibiotics exhibited reductions in non-REM sleep — effects consistent with a microbiome influence. Men in good health had altered deep-sleep brain rhythms after one week of a high-fat, high-sugar diet (although samples were small, not all antibiotics or diets had the same effect).

Inflammation is another conduit. Disrupted gut microbes can raise levels of inflammatory molecules and bile acids that affect clock genes in the brain. In the mouth, an unhealthy microbiome, fueled by an unhealthy diet or lax dental care, can vertically drive local inflammation that narrows the airway and heighten the risk for snoring and obstructive sleep apnoea, UCLA clinicians propose.

From probiotics to practice

Could microbes in targeted attacks be sleep medicine? There are glimmers. The probiotic Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota was linked to improved sleep in a placebo-controlled study of 94 medical students at a related stressful time. A community trial (BIOME), conducted in the UK with 399 adults, identified that self-reported sleep was significantly better with >30 whole-food prebiotic blend versus a calorically matched control; an additional arm was tested with Lactobacillus rhamnosus. These findings are pending peer-reviewed publication and objective measures of sleep.

“I will take a little caution, however it’s early days, and the potentiality for new basic science and translational advances is exciting,” said Dr. Kingman Strohl, a pulmonologist and sleep specialist at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center in Ohio, who was not involved in the study.

Sleep specialists are similarly excited by the possibilities but preach rigor.

Any microbiome therapy needs to be tested head to head with established treatments like cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia and standard therapies for sleep apnoea. All this is not to say that adjunctive probiotics or prebiotics might not assist some of these patients, and if trials support the signal, they might help that subset that does not respond to CBT-I, a nontrivial minority.

What You Can Do Right Now

As the science matures, the practice does overlap with both sleep and microbiome health: maintain a regular sleep window, move bigger meals earlier and eat a fiber-rich, varied plant diet that feeds beneficial microbes. Keep your oral microbiome protected by brushing and flossing everyday and attending regular dental check-ups. Use over-the-counter probiotics with caution; talk to a clinician, especially if you have other medical problems or if you are taking antibiotics.

That’s not to say the headline is that microbes “cause” every bad night. It’s that your internal ecosystem is an element in the sleep system. As circadian disruption becomes an accepted part of modern life — from jetlag to shift work — doing the night shift with our microbial partners may be the quietest sleep aid of all.