DJI lost a court battle to remove its name from a Pentagon military list, the second blow to the world’s largest consumer drone maker this month after a data scandal. The decision likely leaves DJI on a Defense Department list that has dampened government support and commercial relationships across the United States as the Biden administration examines whether the company poses a security risk. The ruling said the action confirmed Washington’s increased focus on dual-use technologies and supported a legal and policy trend that DJI has tried to shift. A federal judge in Washington, D.C., upheld the Department of Defense’s determination that DJI was related to China’s military-civil fusion strategy, arguing that the facts indicated the company’s technology had immediate and future military implications. The ruling was based on the finding that the company’s no-battlefield-use rules did not reflect the products’ capabilities. DJI responded to the ruling, stating that it filed a lawsuit to remove its name from the list drawn up under Section 1260H of the National Defense Authorization Act because the court appeared to be ruling broadly across the entire tech sphere.

Being added to the Pentagon’s list of “Chinese military companies” does not in itself prohibit sales, but it bars access to “covered support” from the U.S. government — grants, contracts, loans and other assistance. It has a second-order effect: many American companies, universities and state agencies won’t buy from entities on the list to cut down on regulatory and reputational risk, even if there is no formal prohibition on purchasing.

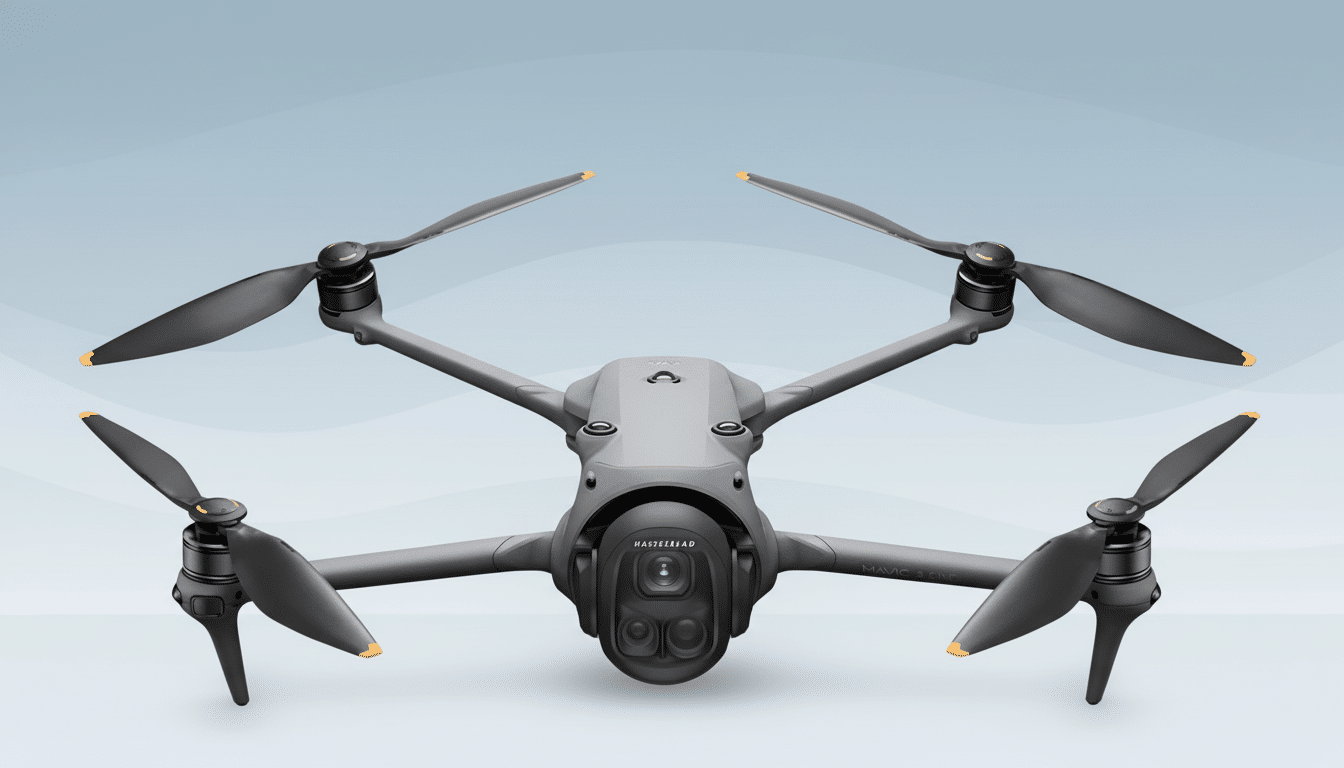

The list is intended to highlight companies that are materially supporting China’s defense industrial base, which underpins military-civil fusion. Analysts at institutions like CSIS have observed that drone platforms, sensors and software are quintessential dual-use devices: as suited for mapping or inspecting a chemical facility as they are for snooping and targeting; it’s one of the reasons DoD classifies them as sensitive.

For American buyers, the immediate outcome isn’t an outright retail ban, but rather a lack of certainty. But procurement officers — particularly at the level of critical infrastructure and public safety — are going to see that ruling as a glaring red flag. Some of the largest agencies already steer clear of foreign-made drones unless they have passed explicit security checks. That trend is likely to grow even more.

The policy headwinds come as federal lawmakers consider further restrictions on drones of Chinese origin and agencies continue to adopt “Blue UAS” frameworks that favor vetted domestic or allied platforms. Industry surveys of public safety programs, such as research from the DroneResponders network, have revealed that a vast majority of departments had previously turned to DJI for reasons ranging from cost to reliability and a mature ecosystem. Replacing fleets in volume might increase budgets and add to training challenges, but it is being done gradually as agencies broaden their buy lists.

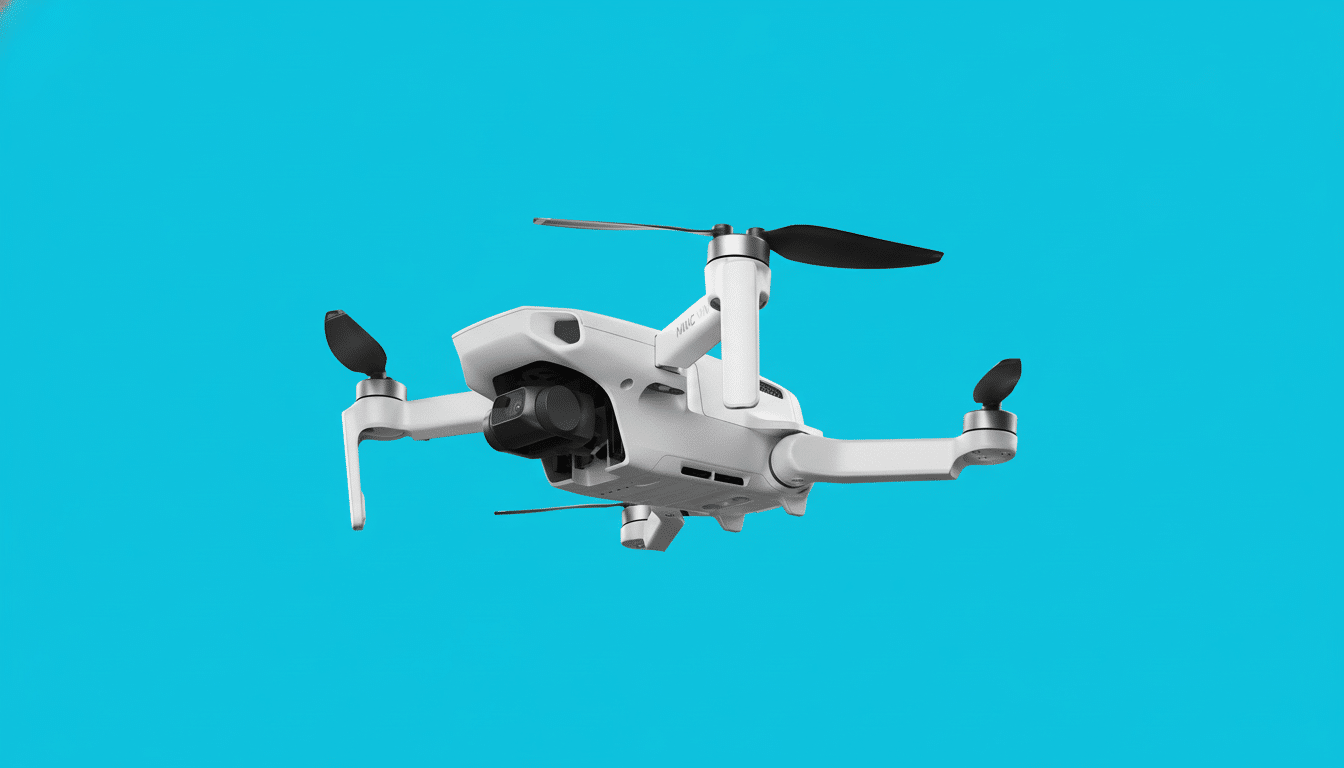

On the consumer side, DJI’s product cadence and U.S. availability have already shown signs of struggle. Retailers say supplies have been in and out of stock, and the company’s latest iteration of its compact flagship has yet to be released domestically — a sign that policy risk is coloring go-to-market decisions as much as pure demand.

Security context and policy barriers facing DJI in U.S.

The struggle for DJI isn’t limited to this court decision. The company is still on the Commerce Department’s Entity List, which prohibits its access to some U.S. technologies, and various federal agencies also have restrictions in place for Chinese-made drones over cybersecurity and supply-chain concerns. Together, even without one overall blanket ban, those measures lay a patchwork of barriers that can discourage large enterprise deployments.

An additional dark cloud is a federal mandate with the potential to force Chinese-made drones to pass a national security assessment in order to remain eligible for some sales and operations in the U.S. The company has indicated it is keen to work with officials to finalize such reviews, but has had difficulty securing a formal process, DJI said, as quoted by Bloomberg. Uncertainty and a lack of an approved pathway mean that sales may be temporarily stalled by distributors or enterprise customers as they wait to see the path forward.

What comes next for DJI, regulators, and U.S. drone buyers

DJI can appeal, or lobby for a risk-based approach that lets its products be assessed model by model and through onshore data controls and third-party audits. U.S. policymakers, meanwhile, will probably keep pushing ahead with country-of-origin restrictions that funnel demand to domestically produced systems provided by companies like Skydio, Teal and Parrot’s U.S. partners.

Bottom line: The court’s ruling cements the Pentagon’s position and raises the compliance threshold for DJI in a key U.S. market. Even if end users have the hots for the products, regulatory gravity now pulls in one direction, toward scrutiny that is tighter, fewer government dollars and a quicker pivot to vetted alternatives.