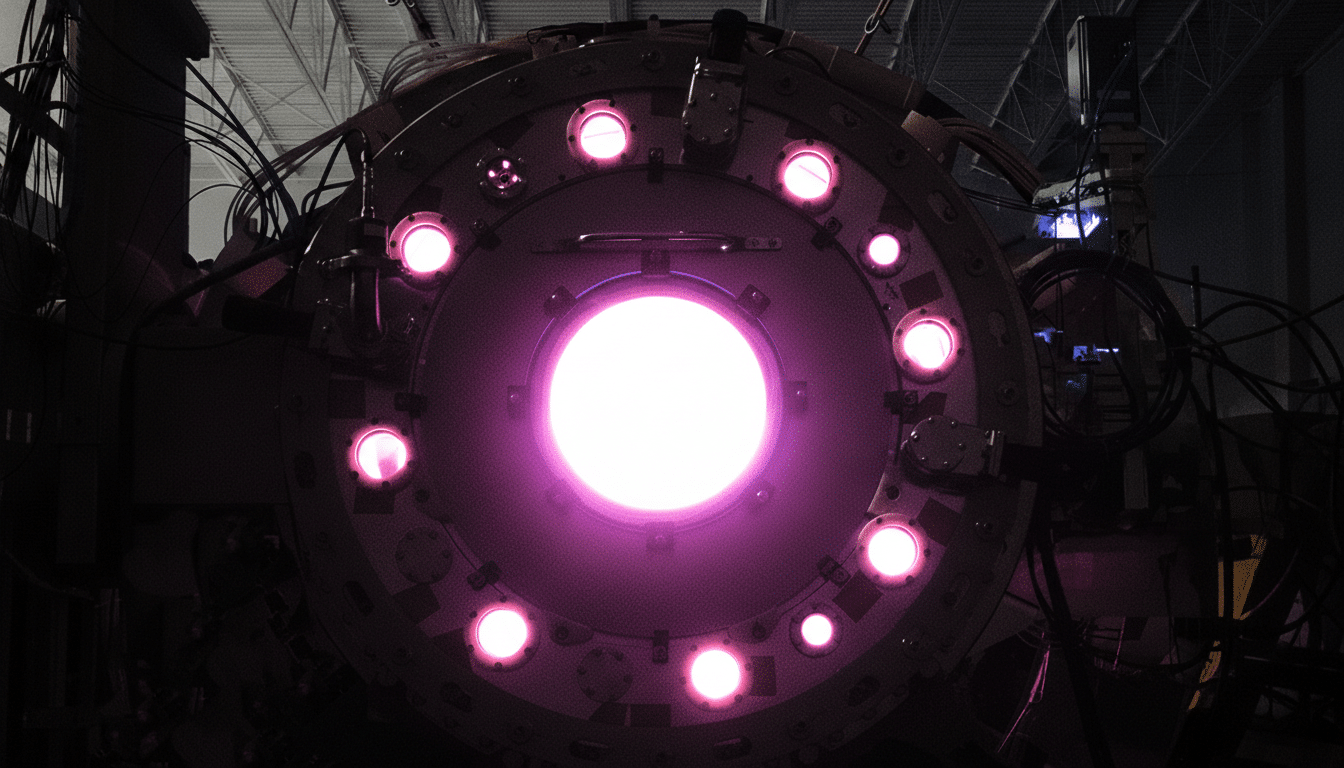

Helion says its Polaris prototype has heated plasma to 150 million degrees Celsius, a blistering mark that represents roughly three-quarters of the temperature it believes is needed for a commercial system. The Everett, Washington, startup also reported operating Polaris with deuterium–tritium fuel, a rarity in the private sector, as it accelerates toward delivering electricity later this decade under a headline power contract.

The company characterized the result as a step-change: as the plasma grew hotter, measured output climbed as expected. Yet Helion still isn’t claiming a physics-first milestone like scientific breakeven. Instead, executives continue to emphasize what really matters for a power plant—turning fusion reactions into useful electrical energy at high efficiency and repeatability.

Why Temperature Matters For Helion’s Design

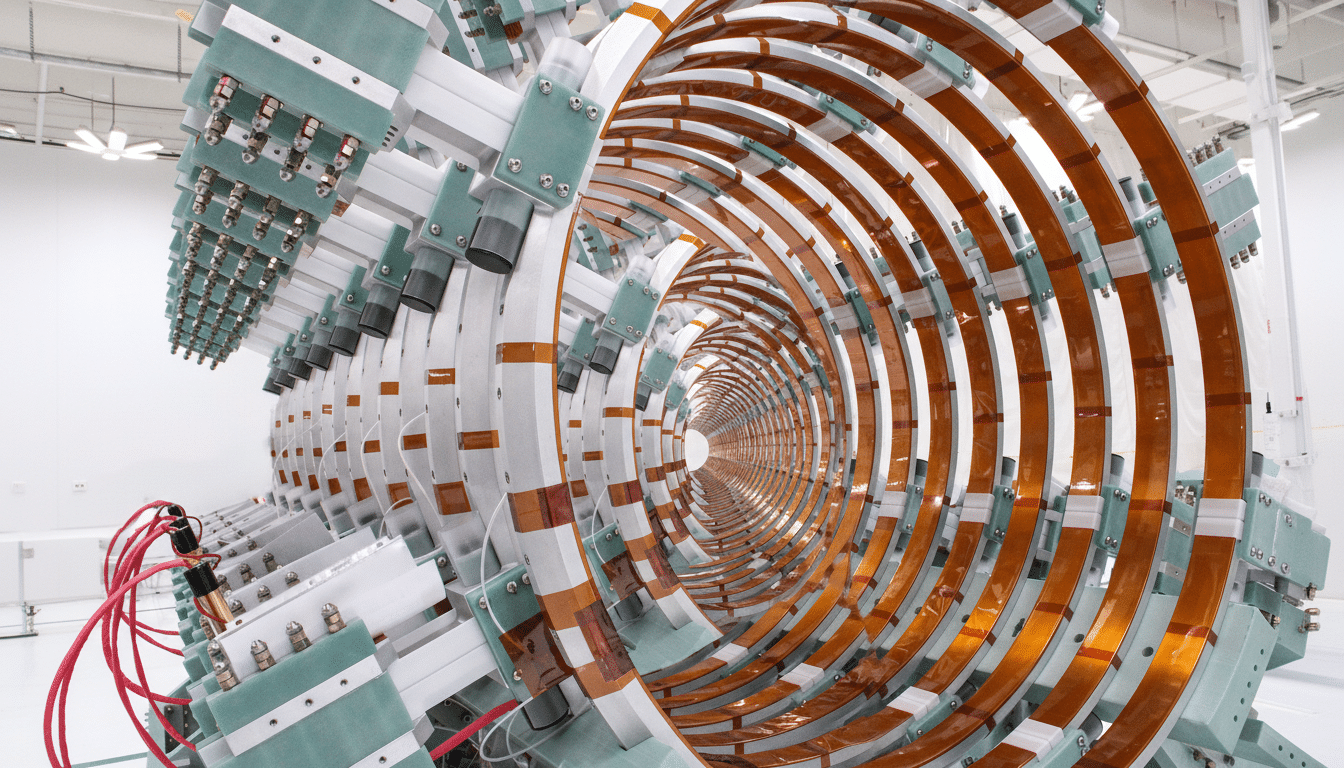

Helion is not building a conventional tokamak. Its approach uses a field-reversed configuration: two compact plasmas are formed at opposite ends of an hourglass-shaped chamber, then magnetically accelerated toward each other and rapidly compressed. The entire sequence unfolds in under a millisecond, and the system operates in pulses rather than steady state.

Because of that architecture and its eventual fuel choice, Helion targets higher core temperatures than many peers. Tokamak-based ventures, such as Commonwealth Fusion Systems, typically aim for temperatures just over 100 million degrees Celsius. Helion’s roadmap requires roughly double that—about 200 million degrees—both to maximize reaction rates and to enable its preferred mode of harvesting power. Hitting 150 million degrees shows the Polaris machine is closing in on that regime.

How Helion Captures Direct Electricity From Fusion

Most fusion projects plan to extract heat to make steam, spin a turbine, and produce electricity. Helion’s pitch is different: capture energy directly from the plasma’s changing magnetic fields. Each pulse compresses the plasma and then pushes back on the reactor’s magnets; the resulting change in magnetic flux induces current that power electronics can collect. Avoiding a steam cycle could lift overall efficiency while shrinking plant footprint and complexity.

Helion says it has refined the recovery circuits on Polaris to bump up how much electricity is harvested per pulse. That may sound like a small tweak, but it’s central to commercial viability. Direct conversion must work at high repetition rates for long durations, all while smoothing power to grid-quality output—an electrical engineering challenge as important as the plasma physics.

Fuel Strategy And Securing Helium‑3 Supply

Polaris is currently running with deuterium–tritium to validate performance and raise temperatures. Long term, Helion intends to switch to deuterium–helium‑3 (D–He3), a path that produces more charged particles and fewer neutrons than D–T—attributes that suit the firm’s direct-conversion scheme and could mitigate some materials degradation.

Helium‑3 is scarce on Earth, so Helion plans to make it on site by fusing deuterium in auxiliary reactions and purifying the helium‑3 that results. The company says its isotope-handling and separation systems have achieved high throughput and purity in testing. If that scales, it would address two thorny problems at once: securing fuel and minimizing supply-chain dependence for an uncommon isotope. It would not, however, eliminate the need to manage tritium carefully—a regulated, radioactive material that requires robust accounting and containment.

The Race To Put Fusion Power On The Electrical Grid

Helion has a power purchase agreement with Microsoft that ups the stakes: this isn’t just about lab milestones; it’s about delivering electricity to a customer. To fulfill that deal, Helion is building Orion, a roughly 50‑megawatt machine distinct from the Polaris prototype. Orion must knit together hot plasmas, durable hardware, and grid-grade power electronics into a cohesive plant.

Competition is fierce. Commonwealth Fusion Systems is advancing a high-field tokamak approach enabled by rare‑earth high‑temperature superconducting magnets. TAE Technologies is pursuing a beam-driven FRC with an eye toward aneutronic fuels. Tokamak Energy, General Fusion, and First Light Fusion each offer variants with different technical risks and potential cost curves. According to the Fusion Industry Association, private fusion financing has topped $6 billion globally, underscoring how much capital is chasing the first grid-connected system.

Milestones That Will Determine Commercial Success

Beyond raw temperature, several gauges will show whether Helion is on track: net electrical output delivered outside the machine, repetition rate and uptime, longevity of coils and first-wall materials under bombardment, tritium and helium‑3 accounting, and independent verification of performance. The fusion community distinguishes among scientific breakeven (plasma energy out exceeds energy into the plasma), engineering breakeven (system-level output exceeds all inputs), and commercial breakeven (power sales cover capex and opex). Helion’s emphasis is squarely on the latter two.

Context matters, too. Government labs have demonstrated fusion ignition in inertial-confinement experiments, proving the underlying physics, but those setups aren’t power plants. What private developers must demonstrate now is reproducible, economical electricity. With 150 million degrees on Polaris and a clear path to 200 million, Helion has narrowed the gap between promise and product. The next test is the hardest one: running a plant that sells power reliably to the grid.