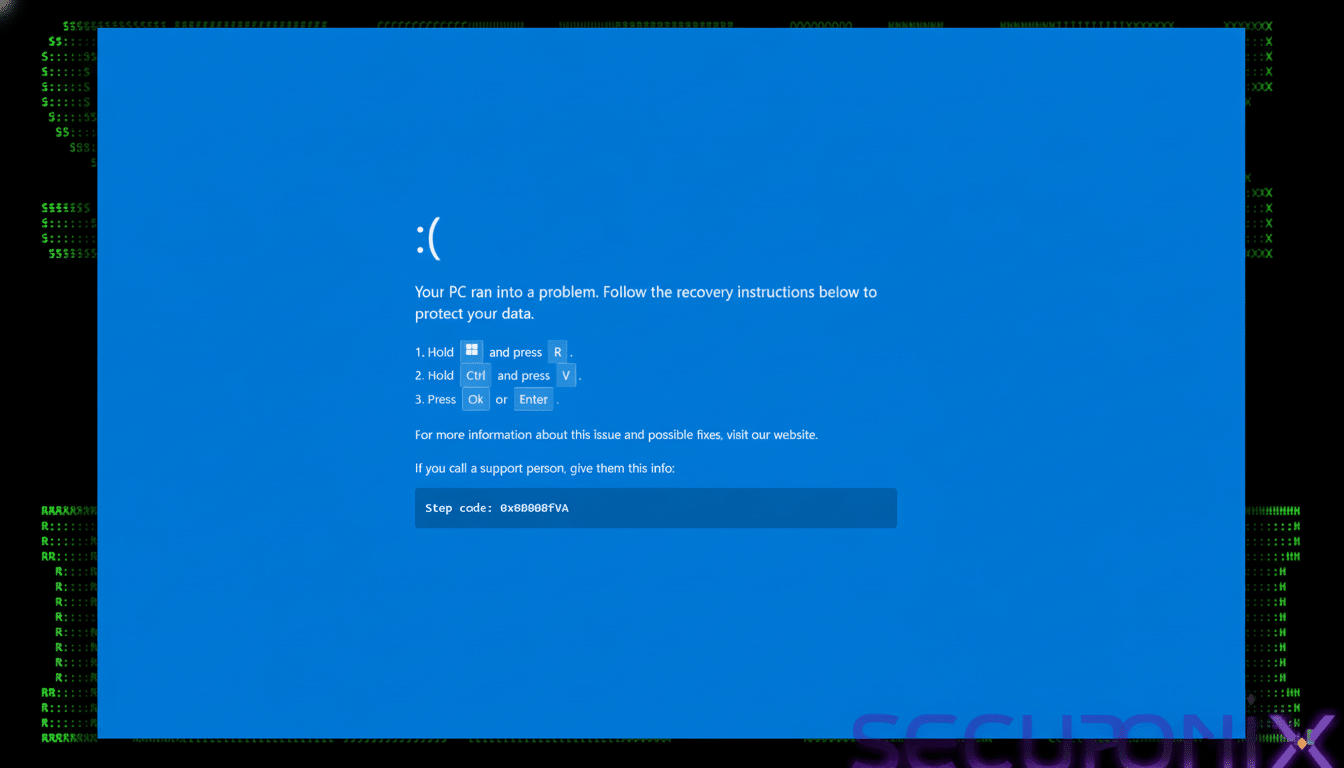

A realistic-looking fake version of the infamous Windows Blue Screen of Death (BSOD) is being used to slip in malware, with a new campaign targeting the hospitality sector. In a blog post today, researchers at security provider Securonix said the campaign combines fake browser-based BSOD screens with “ClickFix” social engineering designed to get recipients to paste malicious commands into their own PCs; that malware then goes on to install a remote access Trojan linked to Russian-speaking cybercriminals.

How the fake Windows BSOD attack operates

The operation, dubbed PHALT#BLYX, begins with a phishing email masquerading as a booking cancellation notice and leading to a lookalike site mimicking a top travel platform. Clicking on the install link at any of those sites does not produce a CNAME; it actually presents a fake CAPTCHA as the landing page, before flipping to a full-page “BSOD” image inside the browser, with alarming text and a step-by-step “fix.”

The “fix” is the trap. Victims are told to paste a script into the Windows Run dialog box or PowerShell. This does nothing; it accesses an MSBuild project (v.proj)—a classic living-off-the-land technique, using a built-in tool to execute code without dropping obvious binaries. The malware disables Windows Defender and achieves persistence by dropping a URL file in the Startup directory to pull down an obfuscated build of DCRat, a commodity remote access Trojan that’s commonly used for keylogging, command execution, and staging additional payloads.

A real BSOD should not appear inside a browser tab. If you’re able to move your cursor, toggle between applications, or scroll a page, then it’s not an actual Windows crash screen. That mismatch is a key tell.

Why this social engineering tactic often succeeds

Blue screens are immediate and terrifying, and the attackers embrace that psychology. They also capitalize on the credibility of a familiar travel platform to prompt action during peak booking periods. Architecturally, the payload chain works well because it rides the coattails of trusted tools—PowerShell and MSBuild—maintaining a low initial profile and thus avoiding basic defenses.

It’s not an anomaly: the Verizon Data Breach Investigations Report has reported year after year that humans are involved in 74% of breaches. Senselessly dangerous click-to-fix campaigns like this that twist people’s arms into “self-infection” may already be more widespread precisely because they bypass so many traditional detection barriers.

Who is being targeted in the hospitality campaign

Securonix says the lures mention reservations and quote charges in euros, suggesting hotels and property managers across Europe. The Russian-language strings in the MSBuild project and the DCRat payload are consistent with known Eastern European criminal ecosystems. Booking and reservation systems have also been targeted by attackers in the last few years, with hospitality as one of the most lucrative targets when it comes to fraud and data theft.

How to detect and halt the fake Windows BSOD scam

If you see a web page telling you that your browser has crashed, it is fake—full stop. Real BSODs grab the whole screen, display a stop code, and don’t tell you to paste commands or download “fixers.” Any website that tells you to open Run, PowerShell, or Command Prompt is trying to get around your defenses.

As a defender, assume that adversaries will leverage built-in tools. Implement application control to limit where MSBuild runs on non-development systems. Turn on tamper protection in Microsoft Defender to prevent unauthorized policy changes. Leverage PowerShell Constrained Language Mode and script block logging to minimize and log such abuse. Watch for shady command lines pulling in remote content, random .url files on startup, and MSBuild making network connections. Living-off-the-land binaries can also be detected by EDR products from major vendors when properly tuned.

Front-desk and reservations staff still need to be conscious of security. Train teams to confirm booking changes from within password-protected sites and not through emailed links, and escalate any page that delivers a “system crash” message in the browser. CISA and Microsoft advice on phishing-resistant MFA and least privilege can help significantly reduce blast radius even if a user slips up.

What to do if you encounter the fake Windows BSOD page

Do not paste anything into Run or PowerShell. Close the browser tab and clear the cache; share the URL with your security team. If you followed the instructions and opened it, quickly detach from the network and alert IT. Responders should isolate the host, grab volatile data if possible, and search for persistence or other artifacts like suspicious Startup entries, modified Defender settings, or MSBuild execution. Rotate exposed system credentials and monitor outgoing connections for DCRat-related C2 activity.

The bottom line: Windows, once again, won’t prompt you to repair a crash through your browser, and authenticated vendors are unlikely ever to want you fixing errors by shoveling obscure scripts into your machine. Consider each “helpful” BSOD that you come across on a web page as the equivalent of a red alert for malware, and lock down the tooling that attackers rely on to make them look genuine.