Facebook Messenger is ending its desktop app, the company announced this week. People who have opened the app are being directed to keep messaging on the web, either through Facebook or directly at Messenger.com for people who do not have Facebook accounts.

The shutdown is part of a wider move to consolidate Messenger into experiences that Meta can alter more quickly and fairly consistently across platforms, while downsizing a product that may have never quite lived up to the premise set by business-focused desktop rivals.

What changed and why Meta is ending the desktop app

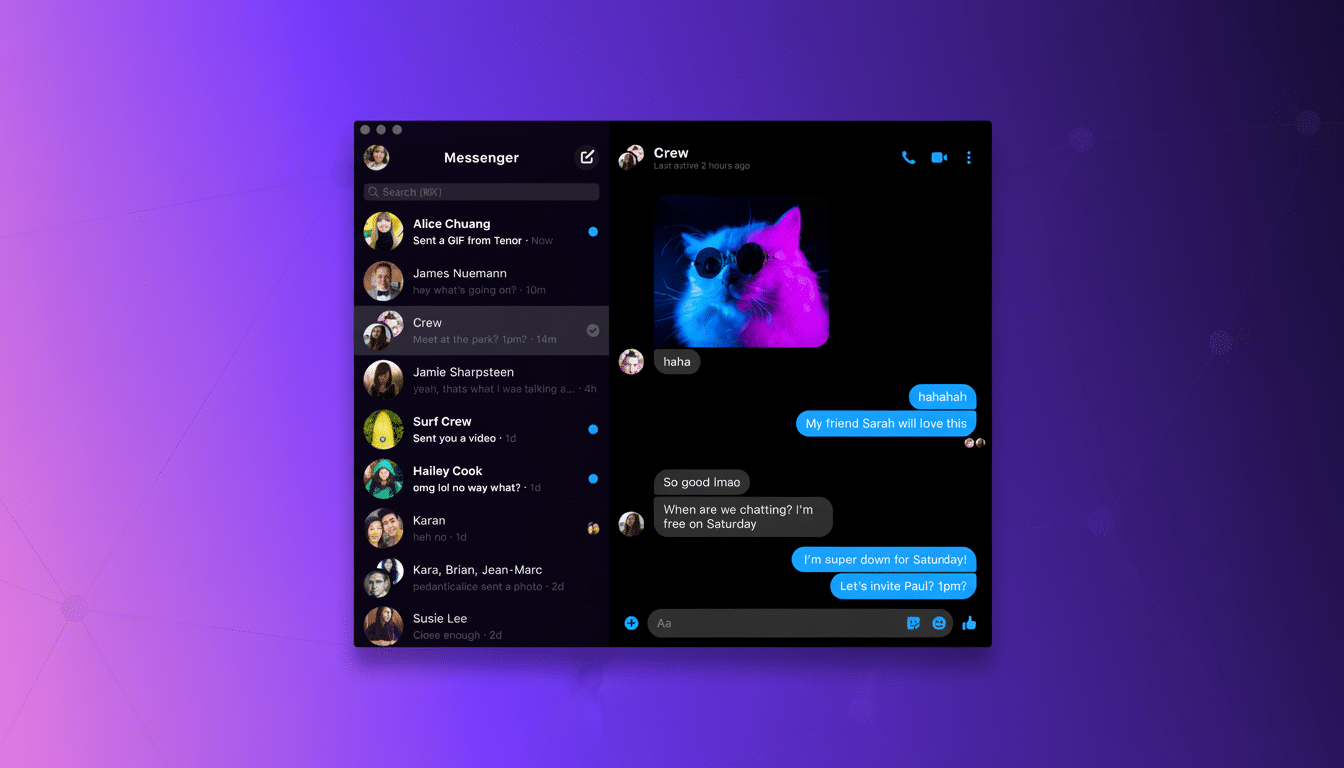

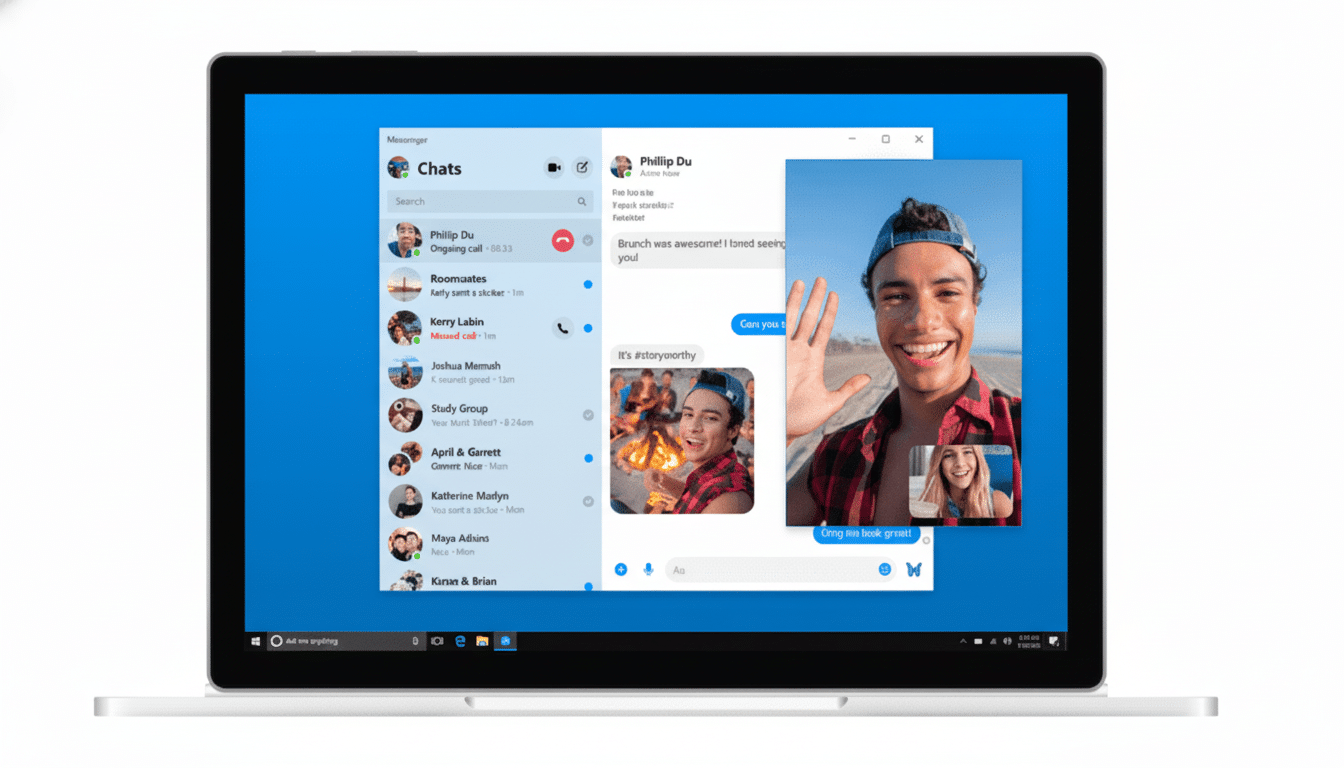

Messenger’s desktop app arrived in the middle of a surge in home office and video chat use, but came without table-stakes features for power users on desktop. It hosted fewer people on video calls than services like Zoom, and it did not come with built-in screen sharing or easy-to-use meeting URLs — features that made Zoom, Microsoft Teams, and Google Meet standard choices for work and school.

In parallel, Meta has been weaving Messenger back into the main Facebook app, a sign that it prefers fewer standalone surfaces. Company guidance has also been to treat the web as the enduring single place for messaging, where features can fall into line at pace without needing entirely separate native codebases per desktop platform.

A brief and complicated run for Messenger on desktop

Beneath the surface, however, Messenger’s desktop narrative had been uncharacteristically fraught. The Mac app was said to have been born on Electron, with a switch over to React Native Desktop and subsequently Apple’s Catalyst — the framework that lets iPad apps be easily ported to the Mac. That balance hasn’t gone over well with many developers, who have complained about Catalyst’s trade-offs, whether that means UI quirks or the extra refactoring they need to do. And users have often noted apps’ not-quite-native feel.

On Windows, the app eventually became a Progressive Web App. PWAs have gotten a lot better — with notifications, offline support, enhanced performance — but they’re still limited compared to everything a natively implemented client can do in terms of deeply integrating with an OS’s surface and screen controls and media handling. The ever-changing architecture on both platforms probably led to doubts about whether the app was a long-term priority.

What current desktop users should do after the shutdown

Current desktop users are being encouraged to transition to the web. Meta’s help center advises people to establish a PIN to enable their encrypted chat history to be recovered when moving between devices or platforms. If you use Messenger without a Facebook account, use Messenger.com; you won’t lose your contacts.

To replicate something closer to the experience on a desktop, turn on browser notifications so you don’t miss any alerts, pin a Messenger tab, and/or set up site-specific browsers or shortcuts (on an iPhone home screen or Android app dock) that take you directly to your inbox. Businesses and creators that moderate large amounts of messages will have inbox access within Meta Business Suite, which combines both the Facebook Page inbox and Instagram DMs with the moderation tools so many teams depend on.

Signals from Meta’s broader messaging strategy shift

Meta has said that it aims to streamline its product offerings and build where network effects are strongest. Messenger remains in use by more than a billion people worldwide, but Meta’s biggest ongoing cross-platform driver right now is WhatsApp and Instagram DMs — both of which anchor commerce transactions, creator engagement, and customer support for many users in the market.

Consolidating the desktop user base into the web also means less duplicated engineering across macOS and Windows, with feature delivery closer to the mobile release cycle as well. With regulatory pressure piling on the need to make messaging interoperable in places like the EU and continued work around end-to-end encryption, a web-first approach can help Meta focus more closely on security and making feature sets consistent across platforms versus chasing niche native clients.

How the desktop messaging landscape compares today

Consumer chat has been mobile-first for a while, and desktop messaging finds its home where work takes place. Slack, Teams, Zoom, and Discord all still very much merit serious desktop investment, because their users rely on screen sharing, multi-window workflows, and tight integrations. Social messengers tend to favor the browser, as capabilities are now more than ample for most use cases and easier to scale globally.

And in that context, the death of Messenger’s desktop app is less a retreat from PCs than it is a reversion to where consumer messaging usage actually takes place. For the vast majority of people it will simply be a tab in place of a different icon. For power users who craved a full native client, it’s the end of an era that never quite made sense for how Facebook Messenger is used today.