A stunning new image from the Gemini South telescope shows the newly detailed interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS brightening as it races into the inner solar system, its coma and tail released in its wake.

The likeness is one of the best glimpses yet of a visitor born around another star and now flaring to life under the heat of our own sun.

What the new image shows

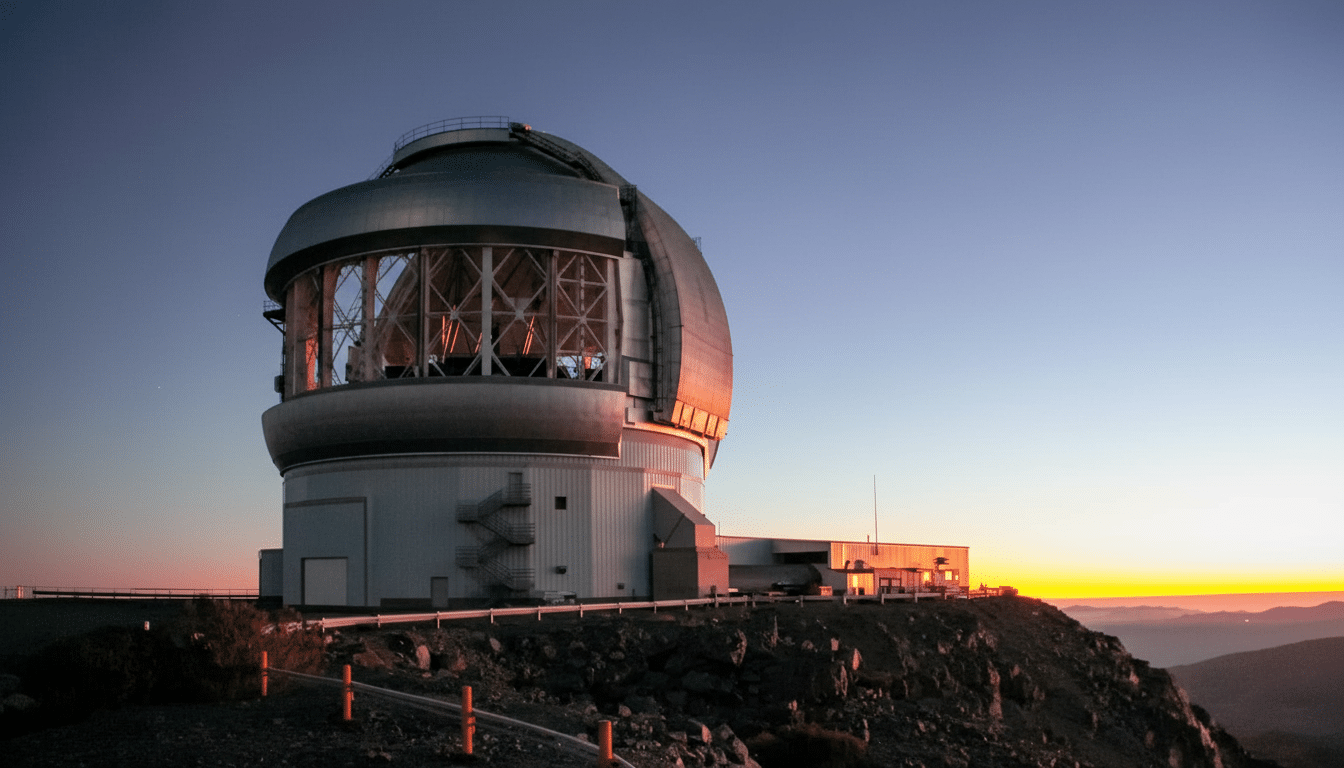

Gemini South of the International Gemini Observatory is owned and operated by NOIRLab and lit as a partnership between the United States National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Research Council (NRC) of Canada, and the National Science Foundation, captured the comet when it was about 238 million miles (383 million kilometers) from Earth, as it cut across the constellation Libra.

The picture, created with the assistance of the Shadow the Scientist education scheme, shows a compact, bright head and an emerging dust tail that is being built up by solar radiation pressure.

By determining how the comet scatters its light and which wavelengths are absorbed or emitted, astronomers can deduce what the comet is made of. Preliminary analyses indicate 3I/ATLAS is dust-poor with properties that resemble those of many comets that originated in our solar system. That convergence suggests that there is common chemistry in planet-forming disks around the galaxy, a tantalizing hint that the raw ingredients of the worlds may be universal.

The observation of a visiting bolide is a significant scientific achievement as well as a reminder that our system is in a restless galaxy, with rare objects like this passing through, connecting our local observations with the larger cosmic story

Karen Meech, a leading researcher on small bodies and interstellar visitors from the University of Hawaii explained.

An unbound traveler, validated by physics

Unlike the countless comets that loop around the sun on elliptical paths, 3I/ATLAS is on a hyperbolic orbit and is traveling too quickly to be captured by the sun’s gravity. An initial tracking put it over 400 million miles from Earth and racing by at about 137,000 miles per hour. And that speed and path suggest an origin beyond our cosmic neighborhood.

The comet was detected by NASA’s Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) telescope, which searches the sky for moving objects.

Its name — 3I — means that it is the third known interstellar object of its kind, after the mysterious ‘Oumuamua in 2017 and the more classic-looking comet 2I/Borisov in 2019.

Closest pass and visibility

3I/ATLAS will be no threat, the European Space Agency said. It will be roughly 149 million miles from Earth, more than one and a half times as far as the sun. At closest approach it will be stationed on the far side of the sun, appearing in dark skies once it emerges from the solar glare.

Astronomers and observatories will be on the watch to see how the coma and tail develop as the comet is cooked. If activity picks up, the dust tail should grow and curve, and emissions from gas could show an ion tail pointing directly away from the sun, the sign of solar wind interaction.

A lab for planet-building chemistry

Interstellar comets are scientific gold. Spectroscopic observations can distinguish emission bands—e.g., CN, C 2 —and may compare these against bands observed in long-period and Jupiter-family comets. If relative abundances and dust properties match, it reinforces the argument for common chemical pathways of planet and atmosphere precursors among the stars of our galaxy.

Preliminary modeling from a few teams indicates 3I/ATLAS may come from an older, less-explored part of the Milky Way.

If so, the object could conserve ices and dust grains that are older than the solar system, with ages possibly over than seven billion years. That makes each spectrum a time capsule, a record of conditions in a far-off, ancient protoplanetary disk.

Separating science from speculation

Any pecular object is going to invite creative speculation, but the evidence here is plain. 3I/ATLAS is unambiguously cometary: it has a coma and a tail, it remains active due to outgassing under solar heating, and it follows a hyperbolic path like ejected interstellar objects. Poor explanations There aren’t any, say ESA and NASA, who focus on these textbook signatures which doesn’t leave much for exotic interpretations.

What researchers will look at next

Observation teams using Gemini and other ground-based facilities will monitor changes in brightness, dust production and gas species as the comet swings around the inner solar system. Among the group’s key objectives are: to determine the dust-to-gas ratio and to help identify the volatiles controlling activity, as well as, if possible, to develop an isotopic ratio to address the location and mechanism of formation.

For now, the new Gemini image offers a sharp, captivating portrait of an unbound worldlet snatching sunlight for the first time in eons — an icy, light-emitting messenger — and an unusual opportunity to read another star system’s history in the flickers and spectra of light.