Jeff Bezos is once more pressing the limits on humanity’s off-world aspirations, this time estimating that millions of people would be living and working in space over “the next couple of decades.” That’s according to the Financial Times, which reported Bezos sharing the vision (which is not unlike that imagined by science fiction genius Isaac Asimov—see video below) with attendees of Italian Tech Week in Turin: a world where we pick space habitats for lifestyle and opportunity, while robots and AI do the heavy lifting.

Why Bezos Thinks the Space Settlement Timeline Is Short

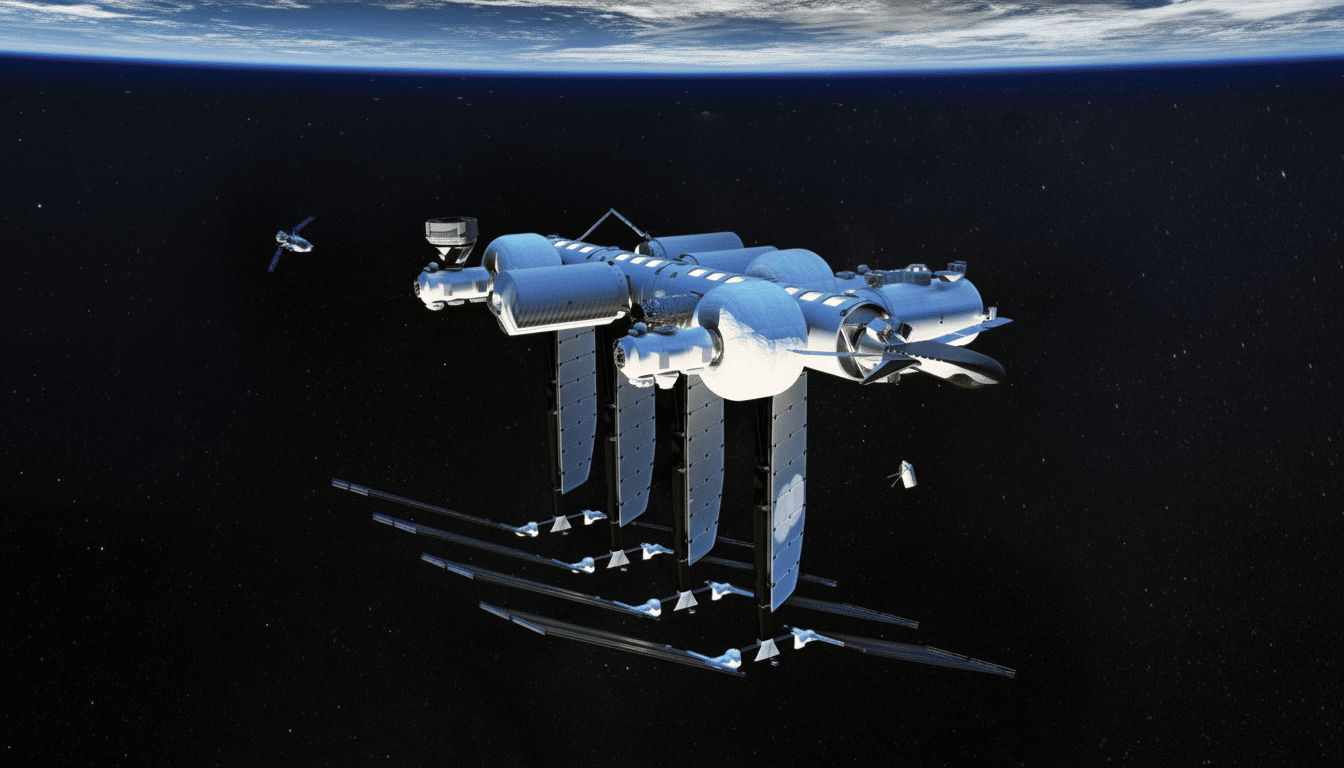

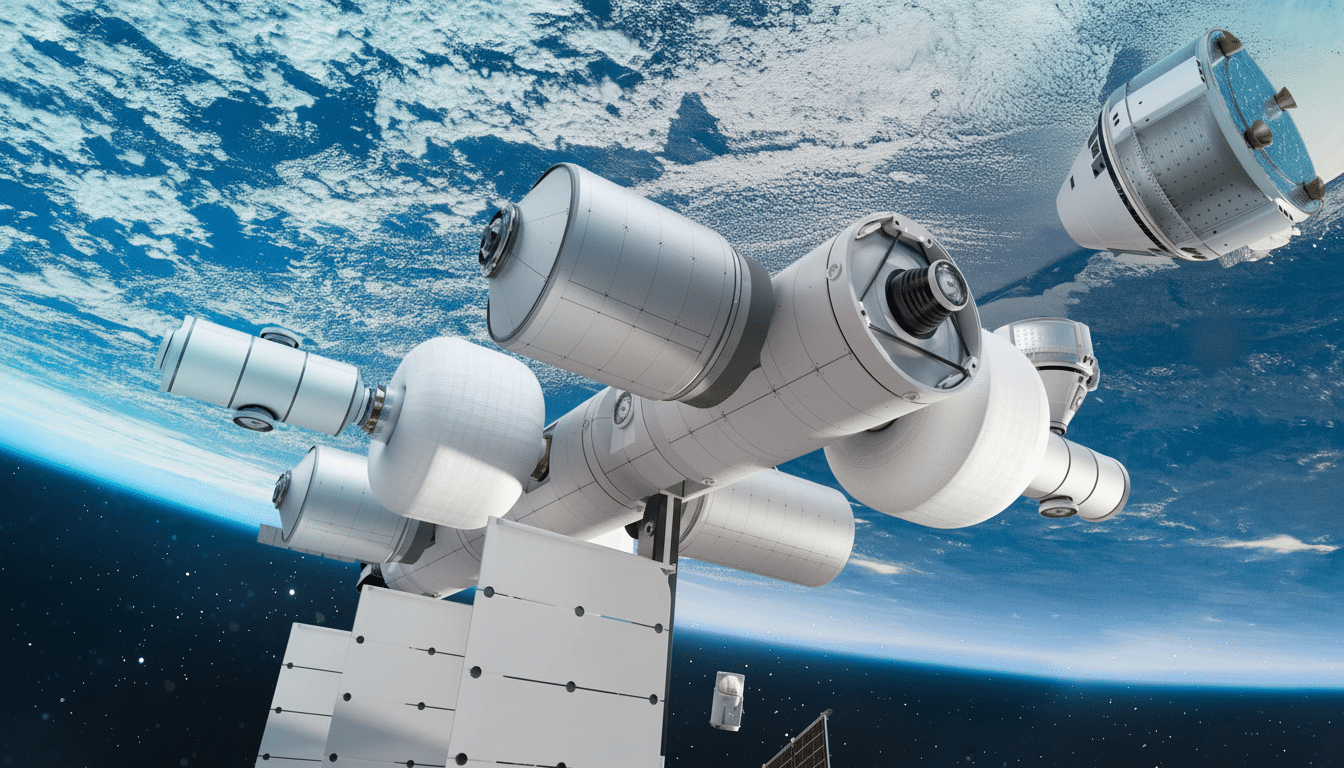

For years, Bezos has embraced the late Princeton physicist Gerard O’Neill’s vision of gigantic rotating habitats miles wide that would provide Earth-like gravity, parks and houses. Blue Origin’s public roadmap directs that course: heavy-lift launch (New Glenn), a commercial station concept (Orbital Reef with Sierra Space) and a lunar lander (Blue Moon) that NASA picked for a crewed mission later this decade. His point is that when the price of lift drops and on-orbit construction comes of age, people, like at any other time in history, will migrate where the money and the tastes are, not just where we happen to go.

- Why Bezos Thinks the Space Settlement Timeline Is Short

- What Millions of Off-Earth Residents Really Require

- Key Swing Factors: Launch Capacity and Lower Costs

- Rivals, Roadmaps, and the Governance Shaping Space

- The Likely Near-Term Reality for Human Space Habitats

- Bottom Line on Bezos’s Bet and What It Could Unlock

He also suggested a provocative variation: orbital data centers fueled by constant sunlight and maintained by robots. The pitch mirrors the ongoing studies of data centers in space by European space companies and the European Space Agency, which could provide ample energy but have prickly issues to solve like heat rejection, radiation hardening, and data latency.

What Millions of Off-Earth Residents Really Require

It’s not a simple straight-line extrapolation from today’s couple of dozen orbital dwellers to millions.

- A closed-loop life support system to manage food, water, and air at city scale.

- Radiation shielding in deep space: attenuating cosmic rays or solar storms usually implies meters of water, an equivalent mass, or habitats constructed from lunar or asteroidal material.

- Gravity simulation: the only way to simulate gravity is with large rotating systems, which aren’t easy to construct, engineer, and keep reliable.

All of that is a logistics problem to be measured in millions to billions of tons. The pragmatic way to do this is to bring materials from off Earth — mining the Moon or near-Earth asteroids, and building structures in orbit. And a canceled NASA OSAM-1 servicing mission has underscored how hard in-space assembly is, even as commercial-satellite-servicing demos by Northrop Grumman and DARPA programs show momentum at smaller scales.

Key Swing Factors: Launch Capacity and Lower Costs

All of that is driven by the economics of lift. Industry estimates set the current price to low Earth orbit on reusable rockets at around a few thousand dollars per kilogram, with fully reusable heavy-lift systems hoping to drive that much lower. SpaceX testing Starship and Blue Origin’s future New Glenn are at the center of that trend; without low-cost, operational, abundant tonnage to orbit, the math doesn’t come close to working for mega-habitats.

Launch cadence is accelerating, too. According to the Space Foundation, the global space economy is now in excess of $600 billion, and commercial services and satellite broadband are the driving forces behind that growth. More flights mean more hardware in orbit, more experience with reusability and more chances to iterate on in-space manufacturing — from fiber-optic materials to bioprinting — critical skills for future habitats.

Rivals, Roadmaps, and the Governance Shaping Space

Bezos’s vision can’t help but inspire comparisons to Elon Musk’s Mars-first plan, aiming for a million denizens of the Red Planet by mid-century. The methods may diverge — orbital settlements vs. planetary outposts — but each relies on scaling the endeavor and developing a sustainable life support infrastructure.

Government plans are coalescing around a cislunar economy. NASA plans to retire the International Space Station by the end of this decade and subsidize commercial successors through its Commercial Low Earth Orbit Destinations program as Artemis lays down a lunar infrastructure step by step. And China’s Tiangong station is already up and running, while its collaboration with Roscosmos on the proposed International Lunar Research Station suggests there will be some space-force twinning going on. The Artemis Accords, signed by more than 40 countries, seek to establish norms for peaceful and commercial operations, including use of resources — rules that are crucial if populations do expand.

The Likely Near-Term Reality for Human Space Habitats

“Millions” in a few decades is quite the stretch by any sober reckoning. A more plausible arc: Hundreds of professionals living and working permanently aboard commercial stations late this decade, a few thousand across low Earth orbit and cislunar space in the 2030s if costs keep falling and habitats prove to be safe and affordable. A small, semi-permanent human presence in the vicinity of or on the Moon is possible within comparable timeframes, driven by robotic logistics and focused in-situ resource tests.

That said, there can be value in big predictions. They invest all day in missing pieces — thermal management for space computing, or autonomous construction, or radiation-safe materials; and the legal frameworks that remove risk from capital-intensive projects. As crucial to what the next phase looks like as rockets themselves will be NASA, the European Space Agency, and national regulators.

Bottom Line on Bezos’s Bet and What It Could Unlock

Bezos is wagering that compounding trends — reusable heavy-lift, commercial stations, AI-enabled robotics and a maturing financing climate — converge sooner than skeptics foretell. If those curves bend the right way, the population in space could increase by orders of magnitude in decades, even if “millions” is aspirational. Either way, the strategic choices about infrastructure, norms, and sovereignty made today will go a long way toward determining whether space becomes more a neighborhood or remains a worksite.