A rare firsthand examination by the YouTuber Mrwhosetheboss has now unlocked two North Korean Android phones to pull back the curtain on an end-to-end system of surveillance and control that’s far beyond the standard absence of Google apps resulting from U.S. sanctions.

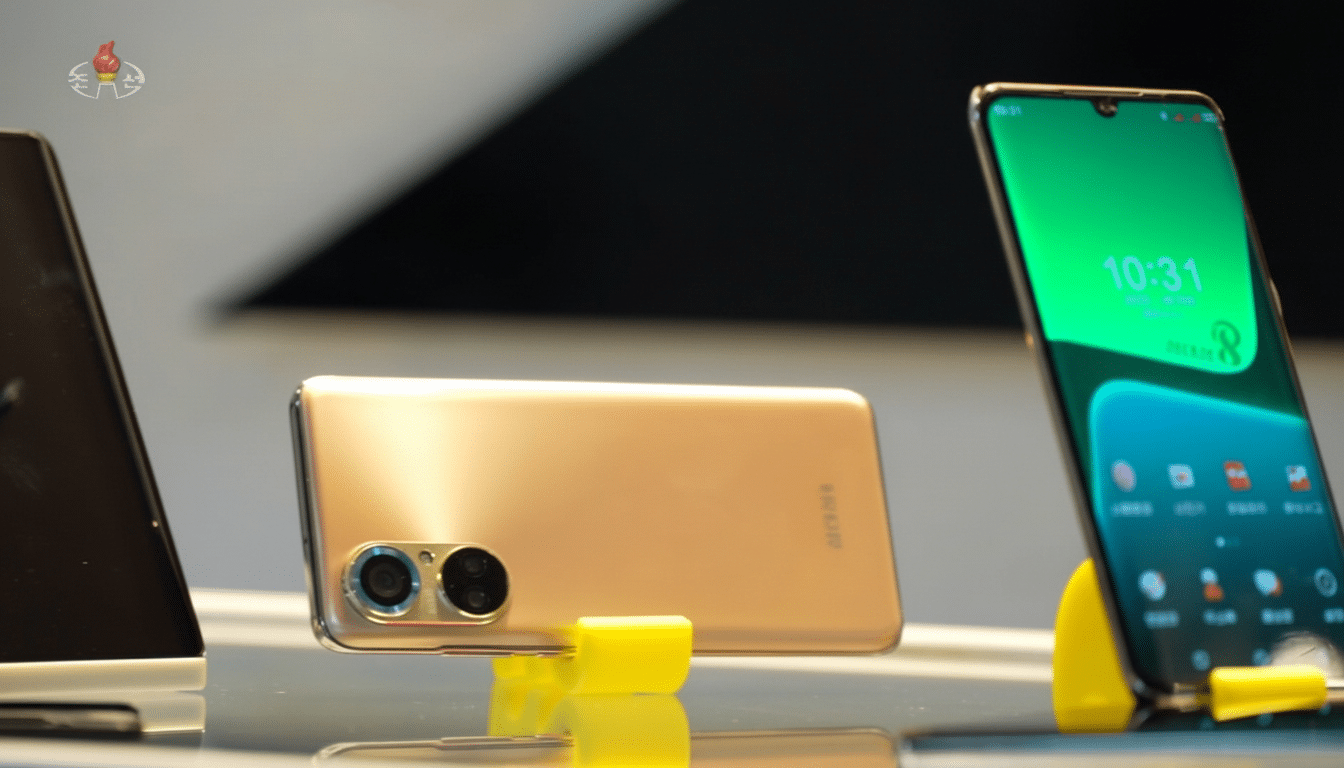

The devices, which include an entry-level model and a premium model named “Samtaesung 8,” seem to have been designed from the boot screen up to enforce language policing, control global internet access, and log practically every action of users.

- How the phones rewrite reality through language controls

- The internet that isn’t: a closed intranet replaces access

- Apps as propaganda and gatekeepers in daily phone use

- Surveillance by design: tracking, locks, and restrictions

- Why it matters beyond one nation’s tightly controlled phones

- The takeaway: a stark look at phones built for control

The result isn’t a smartphone in any traditional sense—but rather its obedient child: an Android fork that mutates everyday functions into an instrument of ideology that blocks contact with the outside world. Parts of these observations are similar to reporting by the BBC and correspond with technical analysis of North Korean software behaviour seen elsewhere.

How the phones rewrite reality through language controls

The keyboard on these handsets is a censor itself. All of which—“puppet state,” another word that cannot even be named in this context but is thereby more closely defined or described than before, and other such terms—have been replaced with asterisks or trigger warnings. Slang and pop-culture references commonly associated with neighbouring media can lead to autocorrections into regime-sanctioned equivalents.

This isn’t your basic web browser keyword blocking. It’s a curated dictionary baked into the operating system itself, meant to overwrite language at creation. It effectively shapes what a user could think of typing—let alone searching, sharing, or discussing.

The internet that isn’t: a closed intranet replaces access

Even though they both run Android 10 or Android 11, neither phone connects to the global internet. Instead, they are confined to a closed-off national intranet—similar to North Korea’s Kwangmyong—containing state-sanctioned sites. Common system settings are restricted: users can’t adjust time zone or date, or sync with other systems. The clock itself even serves as a policy lever.

Core apps such as the browser, the calendar, the camera, and the music player are there with a sense of familiarity but only skin-deep.

Some won’t open; others operate solely within a closed ecosystem, pointed instead to propaganda pages and curated media. There are no approved ways to access popular messaging apps or global sites.

Apps as propaganda and gatekeepers in daily phone use

The software catalog sounds like a civics curriculum. Preloads consist of regime-positive games, biographical tributes to leaders, and a media library littered with foreign films that have the appearance of being pirated, edited, and rebranded for domestic consumption. Entertainment is a sugar coating on story control.

Physical approval at a government-run store is required for any new installation. Approvals are time-limited and device-locked. Based on a walkthrough by the YouTuber, local photos and files are watermarked with government stamps—content without valid signatures can’t be opened or is silently deleted (for example, images or APKs from overseas). This is similar to methods that have previously been seen in the literature on North Korean desktop software, with file watermarking and tamper-resistance built into system functionality rather than added on.

Surveillance by design: tracking, locks, and restrictions

One of the most unsettling behaviours is also, for now, one of the least understood: throughout the day, processes or apps will quietly take a screenshot—that image is used to make sure any drawing you do in a note app lines up exactly with the vector on screen.

File managers only show sanitised folders; Bluetooth sharing is locked down; and normal export paths—from SD cards to USB—are heavily restricted, if they exist at all.

Independent work provides context for these findings. At the Chaos Communication Congress, hackers who picked through North Korea’s Red Star OS described media watermarking and stringent integrity checks that led directly back to users. The BBC has previously reported on similar features in North Korea’s smartphones, such as state-mandated signatures and curated intranet services. The pattern continues like this: traceability and control are baked into the platform, not tacked on.

Why it matters beyond one nation’s tightly controlled phones

Many countries put limits on connectivity or regulate apps, but the design here is totalizing. You are limited to what you can type on the keyboard; discovery is contained within a national intranet; and behaviour is stamped by the UI. Existentially, there is hardly such a thing as a personal computer—just a terminal that happens to be possessed by the state.

Comparative studies by outfits like Citizen Lab have revealed how censorship and surveillance can work at the level of networks or apps elsewhere. The phones of North Korea offer a more radical model: control embedded into the OS and its supply chain, with every kind of agency taken away from the user. For digital rights advocates, it’s a sobering reminder of how rapidly smartphone architecture choices (permissions, app signing, telemetry) can be put to new uses for coercion in an accountability vacuum.

The takeaway: a stark look at phones built for control

The Mrwhosetheboss study provides some of the clearest public evidence to date of how North Korean smartphones work in practice. From dictatorial autocorrect to screenshot tracking and signature-locked files, these Android devices are designed in the service of surveillance and propaganda—not personal expression through communication. For the world beyond China, they are a warning of what happens when one platform controls all levels: privacy and expression disappear by design.