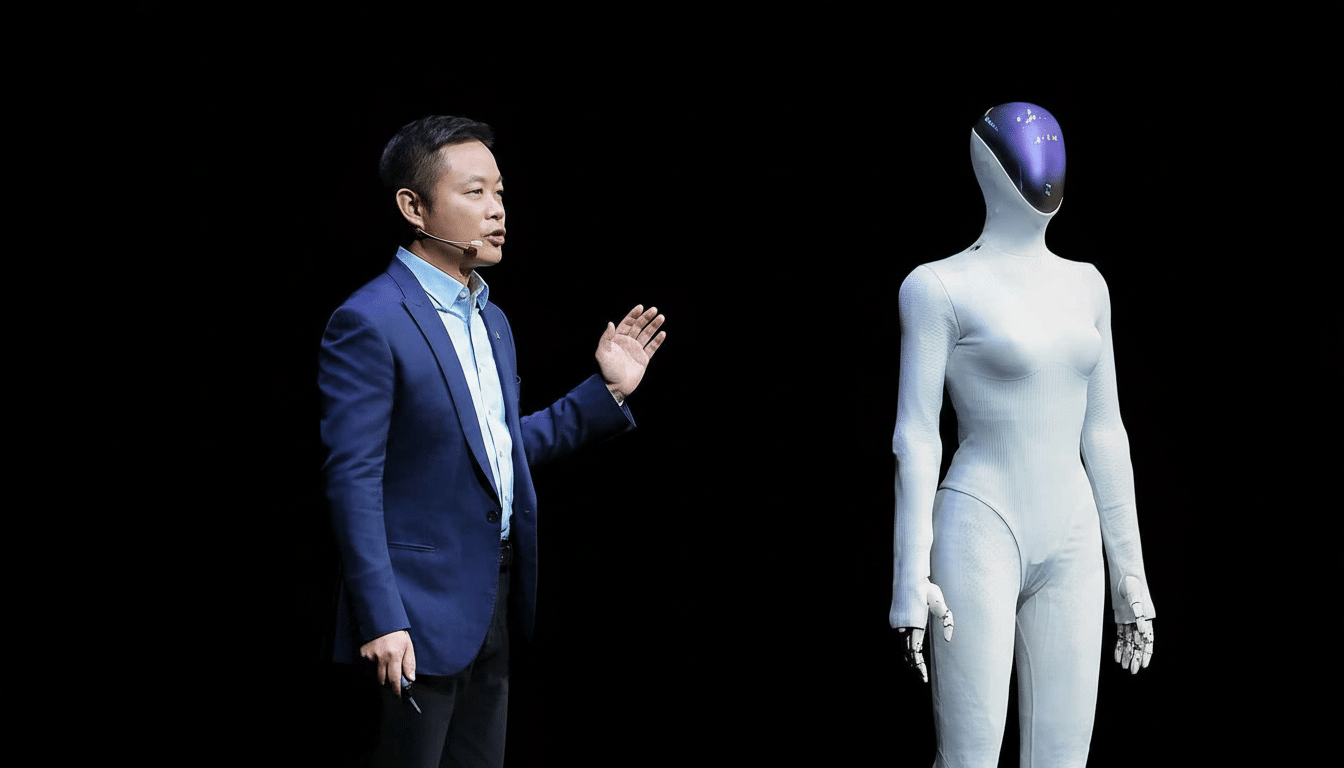

XPENG unveils next-gen humanoid robot “IRON” with visible breasts and a predominantly female form.

The design decision, which quickly spurred chatter on social feeds, is intentional: the company says it’s chasing a body that reads as recognizably human to traverse more seamlessly among humans and provoke warmer responses in everyday circumstances.

- Why the human form still matters for general-purpose robots

- Why XPENG chose female features for its IRON robot

- Design trade-offs and safety considerations for IRON

- Market signals and potential use cases for humanoid robots

- How gender cues in robots raise complex ethical questions

- What to watch next as XPENG advances IRON toward market

Why the human form still matters for general-purpose robots

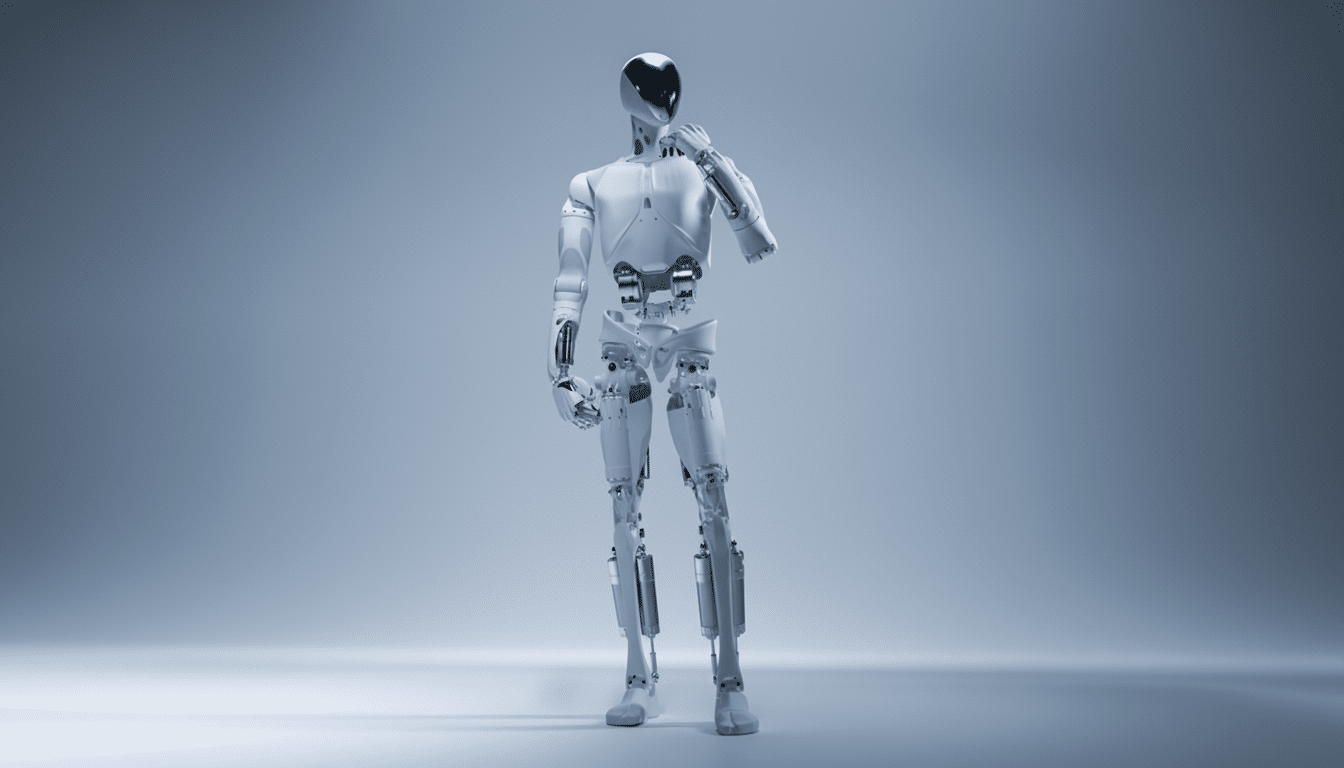

Humanoids are still the most practical form for a general-purpose robotic assistant, because our world is designed for people.

- XPENG leadership says humanoids are still the best way for robots to interact with the very things we want them to help with.

And door handles, tools, stairs, chairs, public transportation, and safety equipment all take for granted two arms and an upright body. Quadruped bases and wheeled bases are stable, but neither can match the limb reach and dexterity, or the turning radius, of a biped with hands in tight spaces or clutter.

The company positions IRON as a long-horizon bet on broad utility, not just another niche demo bot. That jibes with industry momentum: Automakers and logistics companies are currently testing humanoids in part because they can re-use existing infrastructure, rather than build factories or warehouses around robots. Agility Robotics’ Digit has seen action in fulfillment centers, while automakers have trialed platforms such as Apptronik’s Apollo and Figure’s prototype on production lines.

Why XPENG chose female features for its IRON robot

IRON’s shape, according to XPENG’s robotics team, is partly research and part strategy. One reason for the existence of a female-bodied robot at all—the aim is to allow XPENG to test how different demographics respond to form factors as diverse as those of any humans these machines will be working around. The way the team sees it, if people are more comfortable, adoption is easier and scale reduces cost.

There is evidence to support the intuition. Human–robot interaction experiments from institutions such as the MIT Media Lab and the University of Tokyo have demonstrated that familiar, humanlike cues can make perceived warmth, trust, and desire to collaborate increase—especially in service settings in health care. At the same time, makers must be careful not to fall into the uncanny valley, where near-human forms can feel creepy. Softness of surfaces, natural size, and consistent movement are important factors.

Secondary sexual characteristics also produce engineering testbeds. If a robot is specified with a chest, hips, and soft skin, the platform needs to figure out how to do weight distribution and center-of-mass management, compliance without losing balance or gait. That pushes innovations in materials, actuation, and tactile sensing that could help any future version—male, female, or androgynous.

Design trade-offs and safety considerations for IRON

Increasing the mass of the torso can change dynamics of swing and increase power requirements for locomotion. Engineers have counteracted this with composites and hollow structures, but also optimized mass placement to ensure the center of gravity remains within the support polygon during walking. Known caveats: Soft elastomeric skins will reduce injury risks in close contact, enhance grip by adding friction, and increase durability but are difficult to clean and may fail due to cuts in the harsh environment of heavy industry.

XPENG has alluded to customization—including body shape, hair, and full-coverage soft skin—to suit use cases ranging from retail to hospitality to home help. That’s a striking contrast to the neutral, intentionally genderless torsos that other competitive prototypes like Tesla’s Optimus or Figure’s earlier models sport (in an effort to steer clear of any culturally loaded signals—albeit at a cost of approachable friendliness).

Market signals and potential use cases for humanoid robots

The backdrop is a larger race to commercialize general-purpose humanoids. Analysts at large banks have identified humanoids as a league table for the first time this decade and are writing it could be a new multibillion-dollar category, with initial deployment in structured spaces—factory lines, back-of-house logistics, inspection, etc.—followed by general semi-structured environments such as retail floors and hospitals. IFR has predicted double-digit growth for professional service robots, showing a trend of interest in mobile manipulation and human-safe collaboration.

In those cultures, form is not just appearance. “If you can get a robot that looks like a person, and it moves in the same way, it could use all the same tools, reach all the same shelves and go down all the same corridors without special fixtures,” Dr. Lobkovsky said. “And if it exudes warmth rather than threat, it can be deployed in customer- or patient-facing positions without making the customers or patients flee.”

How gender cues in robots raise complex ethical questions

The second you add sex to a thing, you can’t help but look at it with horny eyes.

Putting a chest on a robot invites some questions.

Those who advocate for being more responsible when designing something that has a gendered body attached to it say that design choices, like adding curves simply because they are often associated with women’s bodies or large and strong structures, can perpetuate stereotypes or objectify people in the workplace. UNESCO and the European Commission encourage human agency, non-discrimination, and social good—values that imply developers should test for bias, consider workforce culture, and offer clear customization options, such as gender-neutral models.

XPENG’s position—to provide a range of body styles and let customers decide for themselves—could in theory mitigate some concerns, assuming those decisions are driven by rational analysis of usability rather than marketing whim. Transparent testing with a range of users, and clear data, safety, and interaction boundaries policies will matter almost as much as how the silhouette looks itself.

What to watch next as XPENG advances IRON toward market

IRON is still an R&D platform today, with XPENG indicating intent to ramp toward commercial production. The near-term touchstones to watch are practical: demonstrations of consistent walking on many different surfaces, safe physical interaction with people, handling everyday objects, and battery time that can sustain a full day’s work. If the firm can combine humanoid movement with a friendly form factor—and demonstrate real productivity gains—then choosing to put a female body on a robot may not just be an attractive viral talking point. It will be a market test of what makes humanoids acceptable in the real world.