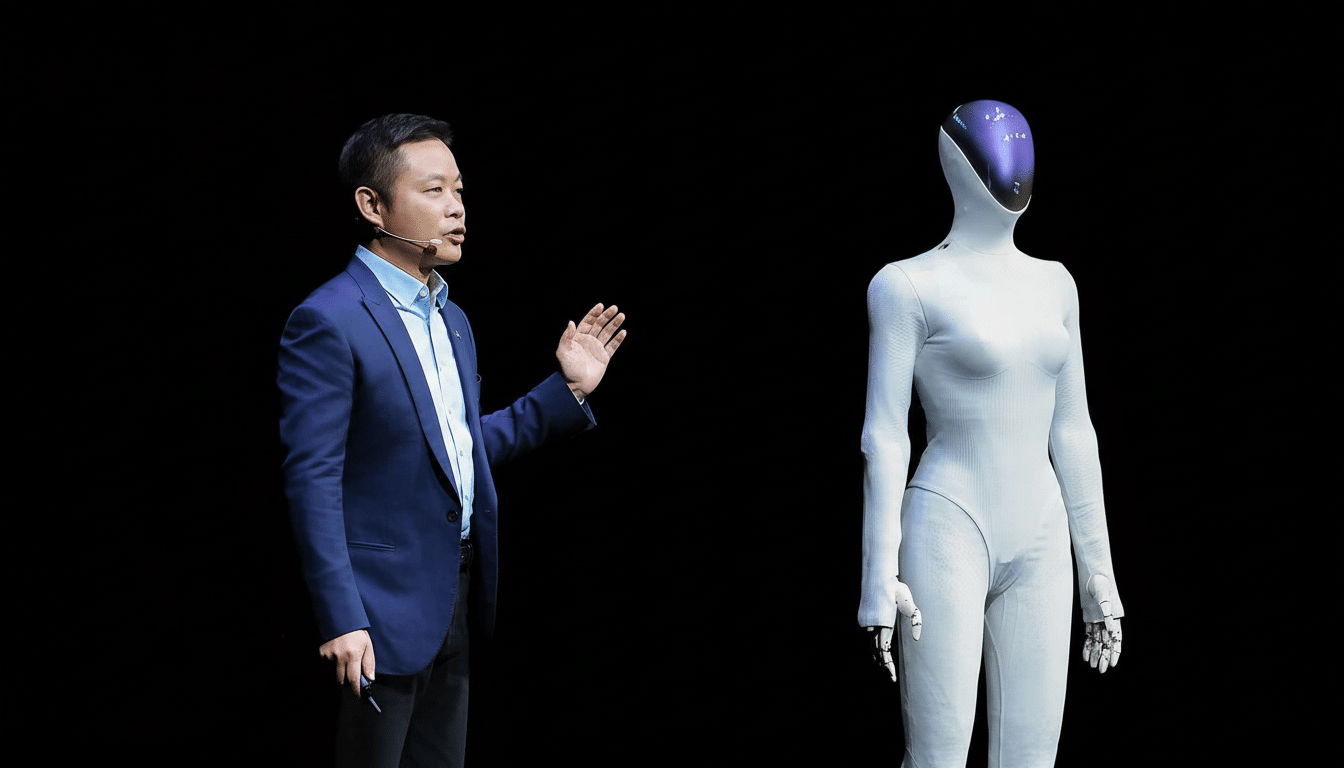

Xpeng stunned its audience by showing off Iron, a humanlike robot that clomped onstage with so much presence it set social feeds humming — then made the spectacle more intense by opening the chassis right there and pointing to circuit boards, cables and actuators. The staged dismantling was designed to silence skeptics who believed that a person could be in the suit-like shell. It was a great way of saying this is not a machine, it’s not a costume.

That reveal comes at a moment in which humanoid robots are inching out of the lab demonstrations stage toward pilot deployments.

But Iron’s uncanny representation of a human body, and its steady pace, give us the shivers for another reason: They touch an ancient cultural reflex of fascination mingled with unease. If that felt deliberate, well, it likely was.

A Demo Designed to Dampen Doubts About Iron

Onstage teardowns are rare in robotics launches, but they fit in an era of hyper-produced demo videos. In unmasking Iron’s internal organs, so to speak, while the event was happening, Xpeng attempted to inoculate its unveiling against the same suspicion that had shadowed other humanoid reveals. High drama is irrelevant when the product walks, talks and looks human — engineering credibility matters.

The company’s naming choice also telegraphs intent: Iron is intended to be understood as a full-stack robotics platform, no small thing. It hints that Xpeng is betting its perception, planning and actuator control strengths — perfected in autonomous driving — can be put to use in bipedal systems that need to balance on their feet and interpret messy surroundings, compensating for stumbles on the fly.

Why Iron Feels Uncanny to Viewers and Designers

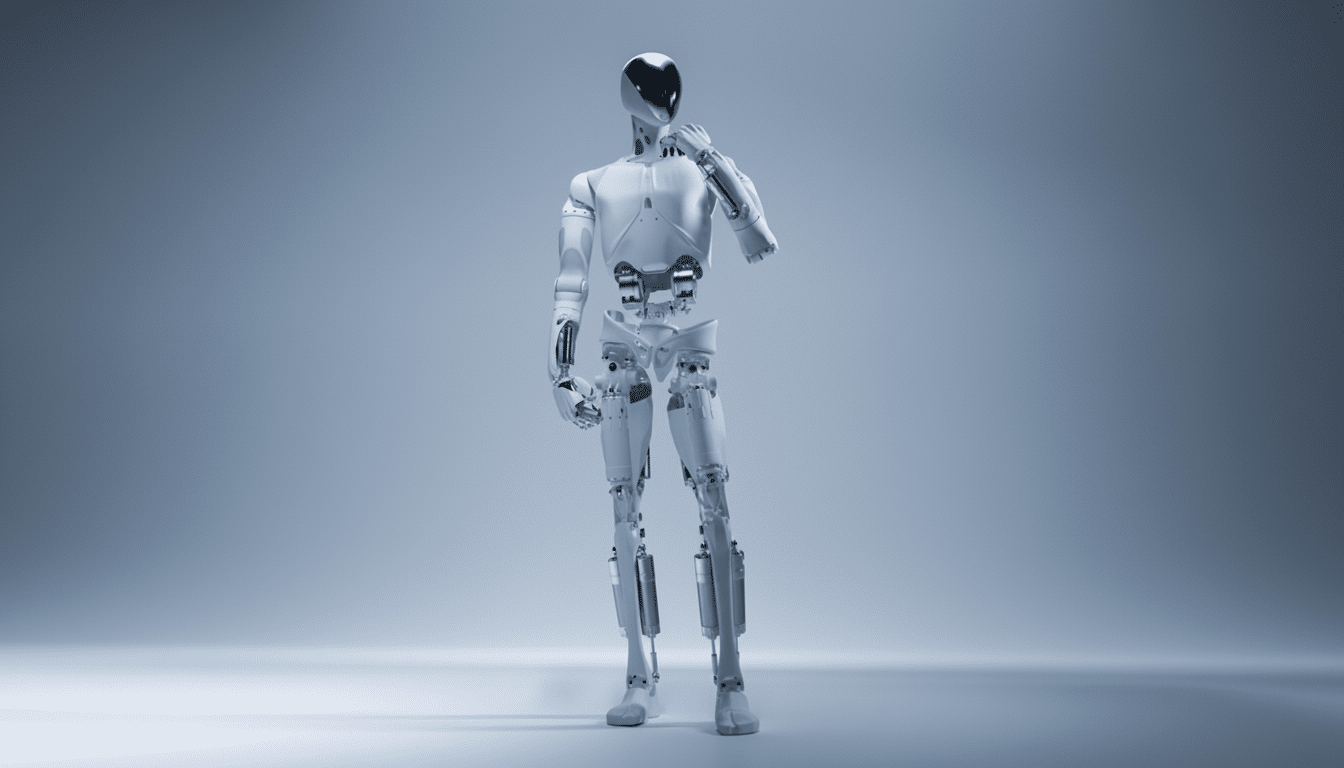

Iron’s ratio and textured exoshell also cozy up to the line that psychologist Masahiro Mori famously identified as “the uncanny valley” — that place where near-human likeness provokes discomfort. Designers borrow from the cues of the human because our world is made for our bodies: stairs, door handles, tools and things at eye level. But it also raises expectations for those choices. The more robot-like a robot appears to us, the less we compare its timing, or intentions or micro-movements — with anything personlike.

Bipedal walking, as it happens, remains among the most difficult challenges in robotics. Moreover, balancing on two legs over an irregular terrain requires the planning of frictional forces, center of mass and external perturbations in a continuous manner. Even the most cutting-edge systems wobble or pause noticeably while switching tasks. That measured cadence — essential for maintaining balance — translates to human observers as creepy restraint.

How It Compares With Today’s Humanoids and Demos

Iron steps into a suddenly crowded field. In controlled lab demos, Tesla’s Optimus has demonstrated simple manipulation sequences. Boston Dynamics was done with its hydraulic Atlas and replaced it with an all-electric successor to zero in on quiet, practical movement. Figure AI’s Figure 01 and Agility Robotics’ Digit are designed for warehouse and logistics chores, with the latter already in pilot at some of the largest retailers. One of Xiaomi’s offerings, CyberOne, showed simple movements and human-robot interaction. All three priorities have varying trade-offs in strength, dexterity and endurance.

Old pros will see a recurring disclaimer: A lot of the “wow” moments are scripted. Publications like IEEE Spectrum in particular are quick to admonish readers that when they watch promotional materials or user-generated content, they must differentiate core avatars (balance, perception, manipulation) from the polish of the cinematics. The true test isn’t on a catwalk, but hours and hours of repetitive labor without oversight or tumbles — the kind of tick-tock reliability standards that factories and warehouses require.

Broader context helps. The world’s existing stock of industrial robots has grown to the millions and mobile service robots are on a rapid upward trajectory, reports the International Federation of Robotics. But despite such general-purpose promise, humanoids are rare in the field because they still face practical constraints — namely, battery life, hand dexterity and safe autonomy around people.

Xpeng’s Strategic Play in Robotics and Autonomy

Why would an electric vehicle firm push into humanoids? The overlap is greater than you’d think. On modern EVs we have robots on wheels that fuse sensors, deal with large perception models, plan trajectories and perform safety-critical actuation. Those abilities transfer to legged systems with similar requirements for localization, scene understanding and real-time control. There are also supply-chain synergies for things like motors and gearboxes and high-voltage power electronics.

There’s also a branding dimension. In a market shaped by autonomy and AI, a flashy humanoid becomes shorthand for technical ambition, and a way to recruit rare talent in a competitive robotics field. Viral attention is not a strategy in itself, but it does speed along recruiting and partnerships — as well as force a company to reveal its engineering cards earlier than would be the case with a spec sheet.

From Viral Clip to Actual Work in Real Settings

What would make Iron more than just spectacle? Three of them: manipulators that can confidently grip and lift diverse objects without crushing or dropping them; locomotion that isn’t tripped up by bumps, slopes and clutter; and autonomy that comprehends tasks beyond pre-scripted routines. Indeed, researchers including those at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory point out that progress in perception-driven manipulation is just as important as legs.

For now, Xpeng accomplished what debuts should: It sparked curiosity and debate. Iron feels unsettling because it leans into human likeness, and the live teardown was a shrewd rejoinder to cynicism. But turning that moment into a product that toils safely alongside people is the long, unglamorous part — and will determine if Iron is more than just an unforgettable arrival.