Four whistleblowers say Meta dissuaded, and watered down, internal research on children’s safety, claiming the company tightened rules to shield sensitive findings from being reported and led researchers to refrain from plain-language risk assessments. The disclosures, which Meta submitted to Congress and were first reported by The Washington Post, heavily emphasize Meta’s virtual reality products and depict a company that has leaned more on legal insulation than on a transparent investigation.

What the disclosures allege

The two current and two former employees who have come forward in recent months said in interviews that after high-profile revelations about youth mental health on Instagram, Meta revised its internal policies to restrict inquiries on children, harassment, race and politics. Researchers were told to work with company lawyers to put communications under attorney-client privilege, and “not use terms such as “not compliant” or “illegal” when writing up risks,” according to the documents described to lawmakers.

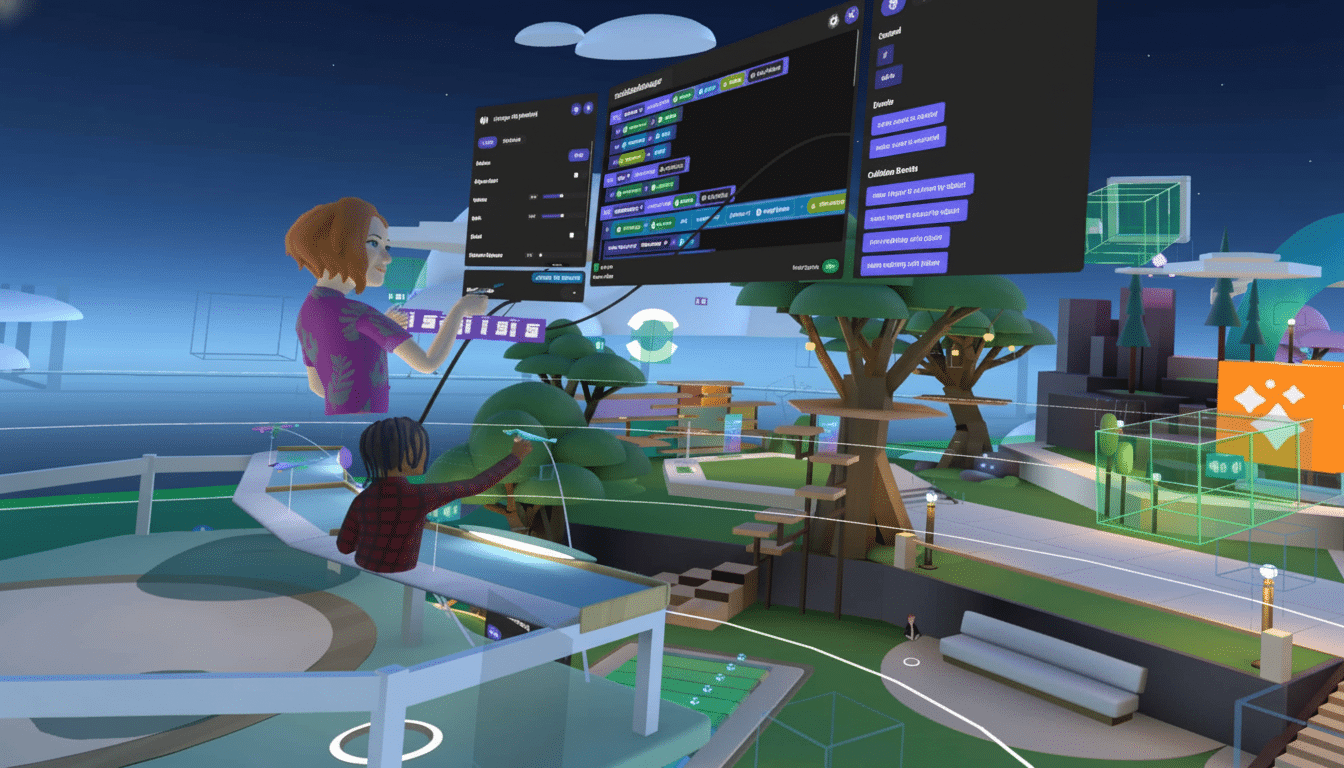

One former researcher, Jason Sattizahn, said he was asked to delete recordings of interviews in which a teen said a 10-year-old sibling had been sexually propositioned on Horizon Worlds, Meta’s social VR platform. The whistleblowers also allege that employees were instructed not to talk about how children under 13 access VR experiences, even though the company has policies in place that prevent them from using the service. In one internal test described in the materials, Black users were said to have heard racial slurs within seconds of entering a virtual reality space in one account, reinforcing the allegation of the internal whistleblowers that enforcement and safety tooling was not up to the task.

Meta did not immediately offer a detailed rebuttal of the new claims, but the company has previously said that it pours substantial resources into the task of ensuring safety and integrity and uses a combination of policy, detection systems and human review to safeguard teenagers across its platforms.

Policy changes following previous leaks of research

The reported crackdown on language and research scope came after earlier internal research findings, revealed by the Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen, that Instagram could harm the well-being of teenage girls. Those disclosures set off intense examinations by U.S. lawmakers and regulators, and ignited a larger debate about how platforms quantify, report and manage risk to youth. The whistle-blowers, including the person who spoke to The Times as well as nearly a dozen current and former employees who witnessed some of the discussions, said Meta’s subsequent policy shifts now made it more difficult to deliver unvarnished analyses of child safety, especially in VR.

The dynamic here should sound familiar: companies contend that they’re protecting sensitive data and preventing misconstrual, while critics argue that legal privilege and muted language can obfuscate the scope of harm. For researchers, the effect can be chilling, as they create less specific documentation, do fewer replicable tests and wait longer to escalate programs that require immediate solutions.

VR dangers and compliance loopholes

VR is particularly difficult to police. Voice chat, virtual avatars and user-created worlds that exist in real time muddy the waters of grooming, sexual content and harassment. Safety advocates have cautioned that age gates are easily subverted, and that moderation will have to marry AI, proactive room-level controls and swift human enforcement. The accounts of the whistleblowers indicate that Meta’s safety measures in Horizon Worlds have not consistently prevented younger children from gaining entry or kept teens immune from abuse.

These claims come as scrutiny expands beyond social feeds. Meta’s AI rules once permitted chatbots to have “romantic or sensual” conversations with minors before they were tightened, as Reuters reported—a demonstration of how the deployment of new product categories in a mindful-phone world can swiftly expose children to risk if policy doesn’t keep up with rollout.

Stakes: legal, regulatory, and reputational

U.S. state attorneys general have filed lawsuits against Meta, claiming it designed hooks that are harmful and addictive to young users. The Federal Trade Commission wants to bolster an already existing privacy order by imposing greater restrictions on how companies collect and use the personal data of minors. In Congress, measures such as the Kids Online Safety Act seeks to establish a duty of care and greater oversight for teen experiences on the internet.

On the global stage, the European Union’s Digital Services Act would oblige big platforms to audit systemic risks, including abuse against minors, and to give regulators access to the data and methodologies. The U.K.’s Online Safety Act includes obligations around preventing grooming and harmful content. If the whistleblowers’ allegations are borne out, regulators could mandate stricter risk assessments, unfettered access for auditors and more transparent documentation of how trade-offs are made when it comes to child safety.

Meta’s defenses, and what to watch

Meta has long played up its safety investments, including tens of thousands of employees working on integrity, dedicated youth well-being teams and features like Family Center, parental supervision tools and teen-specific defaults to limit unwanted contact. For VR, the company points to features on personal boundaries, safe zones, default settings that are more conservative for younger users and reporting tools that can be reached from inside headsets.

Key questions for lawmakers and regulators now include: Were researchers discouraged in a systematic way from documenting young people’s risks in stark language of the kind? To what extent were operational issues (legal or otherwise) protected from internal escalation and external supervision? And how effectively did Meta translate known risks into product changes and enforcement enhancements?

The revelations up the stakes for the independent audits of both content moderation and product design, in VR and AI-driven experiences. They also highlight a larger lesson from previous platform crises: In the absence of transparent research and unequivocal language, youth safety concerns can fester in the chasm between what teams know and what leaders are willing to admit.