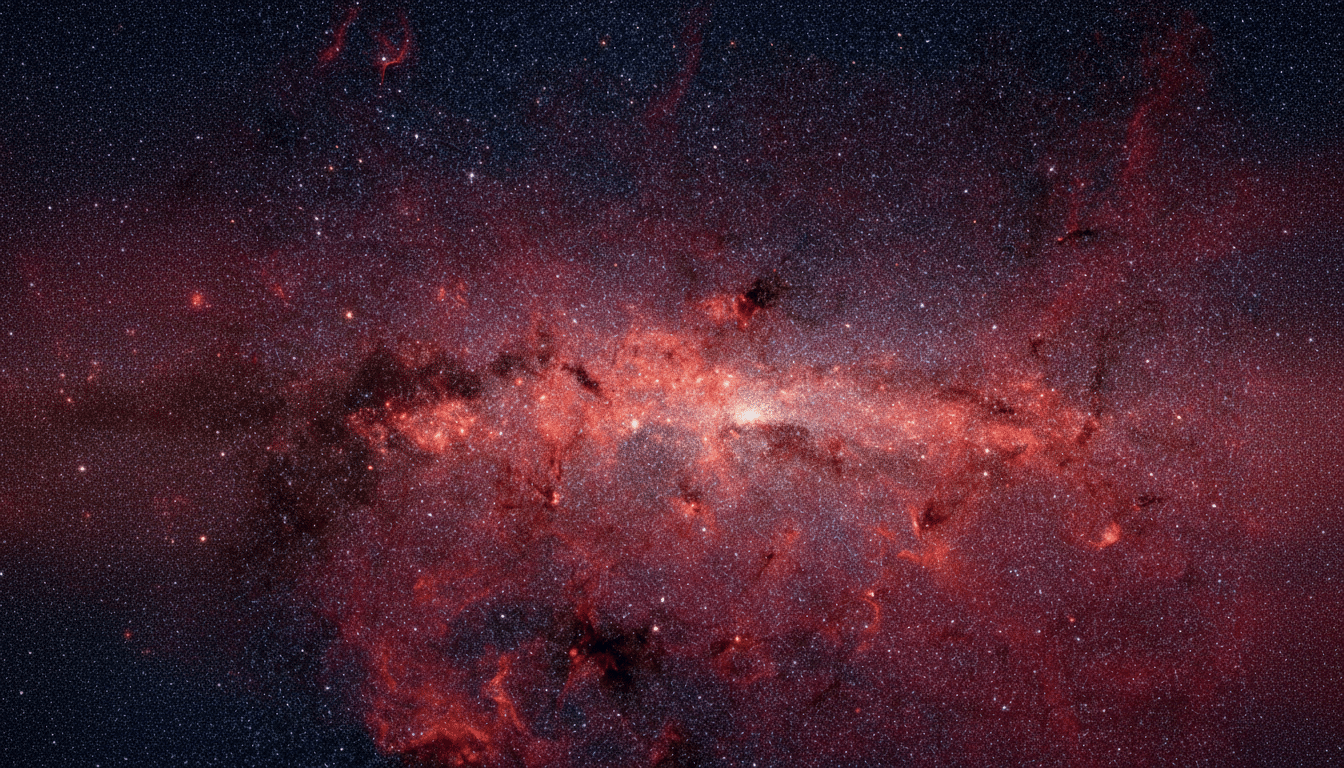

The James Webb Space Telescope has provided its most spectacular peek — so far — at a colossal, star-farming cloud that is just a few hundred light-years from the supermassive black hole lurking at the Milky Way’s heart. The pictures reveal a teeming stellar nursery woven with filaments of dust and studded in clear detail with knots of glowing protostars.

But what makes this view unique is not just that it’s beautiful, but also prolific. Despite having only about one-tenth of the star-forming material, it is responsible for almost half of the new stars in the Galactic Center region, according to NASA. Knowing why this cloud is so prolific at forming stars may revolutionize models of how massive stars erupt in extreme places.

Massive stars produce the ingredients that make planets — and, eventually, life. But the exact cocktail of gravity, magnetic fields, turbulence, and radiation turning cold gas into blinding suns is still being nailed down. Webb’s infrared sensitivity and acuity may allow astronomers to take their best shot yet at teasing apart those forces in one of the galaxy’s most vexing laboratories.

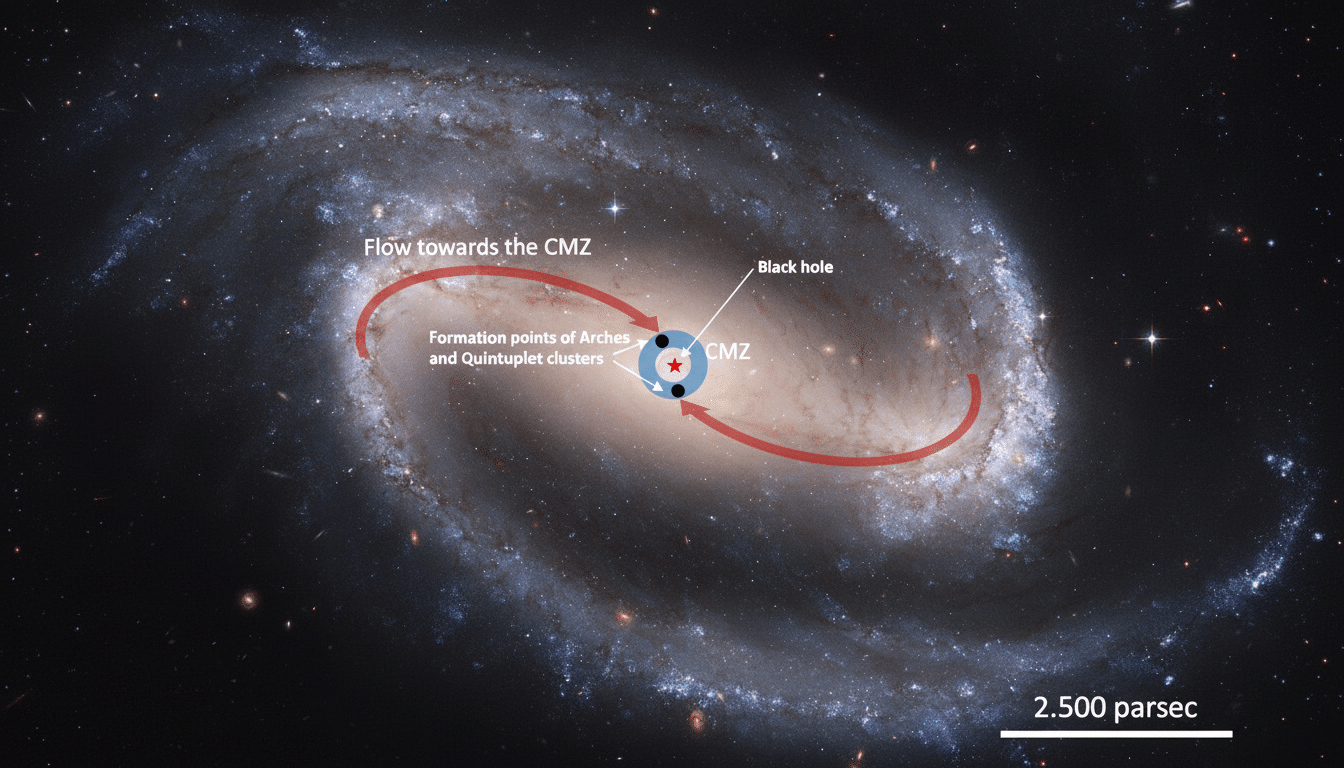

Inside The Milky Way’s Central Molecular Zone

Sagittarius B2 resides in the Central Molecular Zone, a ring-like band of dense gas and dust that surrounds the Galactic Center some 26,000 light-years away from Earth. The conditions are extreme here: gas pressures are high, turbulence is relentless, and magnetic fields are stronger than in the neighborhood of the Sun. In that crucible, B2 shines as one of the most massive molecular clouds in the Milky Way, tens of light-years long and home to compact “hot cores” where complex chemistry and star formation are cooking with gas.

Webb’s Near-Infrared Camera and Mid-Infrared Instrument uncover what shorter-wavelength telescopes cannot: material glowing as warm dust that exposes knotted filaments and glowing cocoons around young stars. Molecules and hydrocarbons glow with emission that maps the shock fronts of gas impacting each other and falling down. Teams led by the Space Telescope Science Institute, which processed the new data, emphasized such interplay with dramatic clarity.

The astronomers who lead the program, including Adam Ginsburg and Nazar Budaiev, emphasized in NASA statements that Webb’s detail at last permits a census of the cloud’s youngest residents.

With the clusters now resolved at even finer scales, scientists are able to sum up the population of forming stars and determine how many form, where they form, and how they interact with the gas that created them.

The Reason Sagittarius B2 is Better Than Its Neighbors

Other clouds close to the Milky Way, like Sagittarius C, contain similar amounts of gas but have far fewer newborn stars.

New Webb observations, along with those in radio and submillimeter wavelengths from instruments including ALMA and the Very Large Array, indicate that magnetic fields and intense turbulence in regions of the Central Molecular Zone can resist gravity, halting the collapse even when there’s plenty of gas.

Sagittarius B2, it seems, has crossed a threshold: its most dense clumps are so weighty and squat that gravity wins out. In theories of star formation, this balance is frequently quantified by specifying the mass-to-flux ratio and virial parameter — numbers that measure what fraction of gravity overcomes magnetic tension and turbulent pressure. In the cores of these B2s, those numbers are likely tipped in favor of rapid collapse, which generates a burst of high-mass stars that drench the region with ultraviolet light and mighty winds.

That distinction matters well beyond a single cloud. There is growing evidence that the Galactic Center might form proportionally more massive stars than those in the Milky Way’s suburbs — a “top-heavy” initial mass function. If confirmed with Webb’s counts, it would change estimates for how rapidly the region enriches itself with heavy elements and how feedback from young stars shapes the central ecosystem.

What Webb Can — And Cannot — See in Sagittarius B2

That is not to say that the darkest areas of the new images are empty. They are so coated with dust that not even Webb’s infrared eye can peek through them. These opaque knots probably conceal the youngest protostars of all — embryonic stars whose heat can still warm their surroundings but are still not revealed through thick shrouds. To peer into those depths, astronomers will supplement Webb with observations at longer wavelengths that can sneak through the densest material.

The line of sight toward the Galactic Center is also famously opaque, with overlapping structures at different distances. Webb’s spectral capabilities help tease those layers apart by reading the fingerprints that molecules and dust have left behind, transforming a two-dimensional image into a three-dimensional map of temperature, composition, and motion.

The Next Questions for Understanding Sagittarius B2

The team has also proposed follow-up spectroscopy to infer the masses and ages of young stars in Sagittarius B2. Determining that distribution will help confirm whether the region is genuinely dominated by large stars and elucidate how long the current burst of star formation has been going on — whether it spans millions of years, or instead was triggered more recently as gas streams orbit through the Central Molecular Zone.

Webb’s new view underscores for NASA, the European Space Agency, and the Canadian Space Agency why infrared astronomy is game-changing. By slicing through the Milky Way’s dustiest realms, the telescope allows researchers to peer inside a natural laboratory that forms the heart of our galaxy and watch stars forming in almost real time. The picture is stunning; the physics it reveals may be even greater.