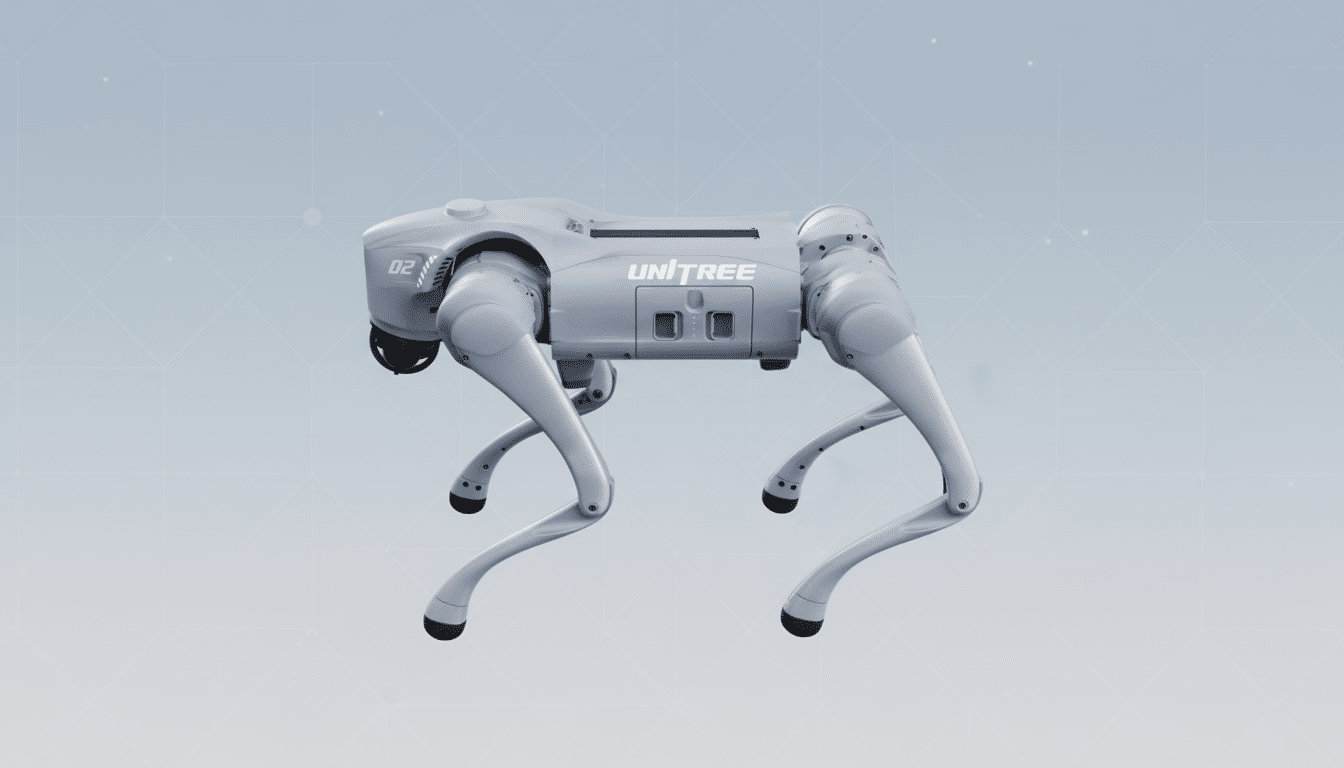

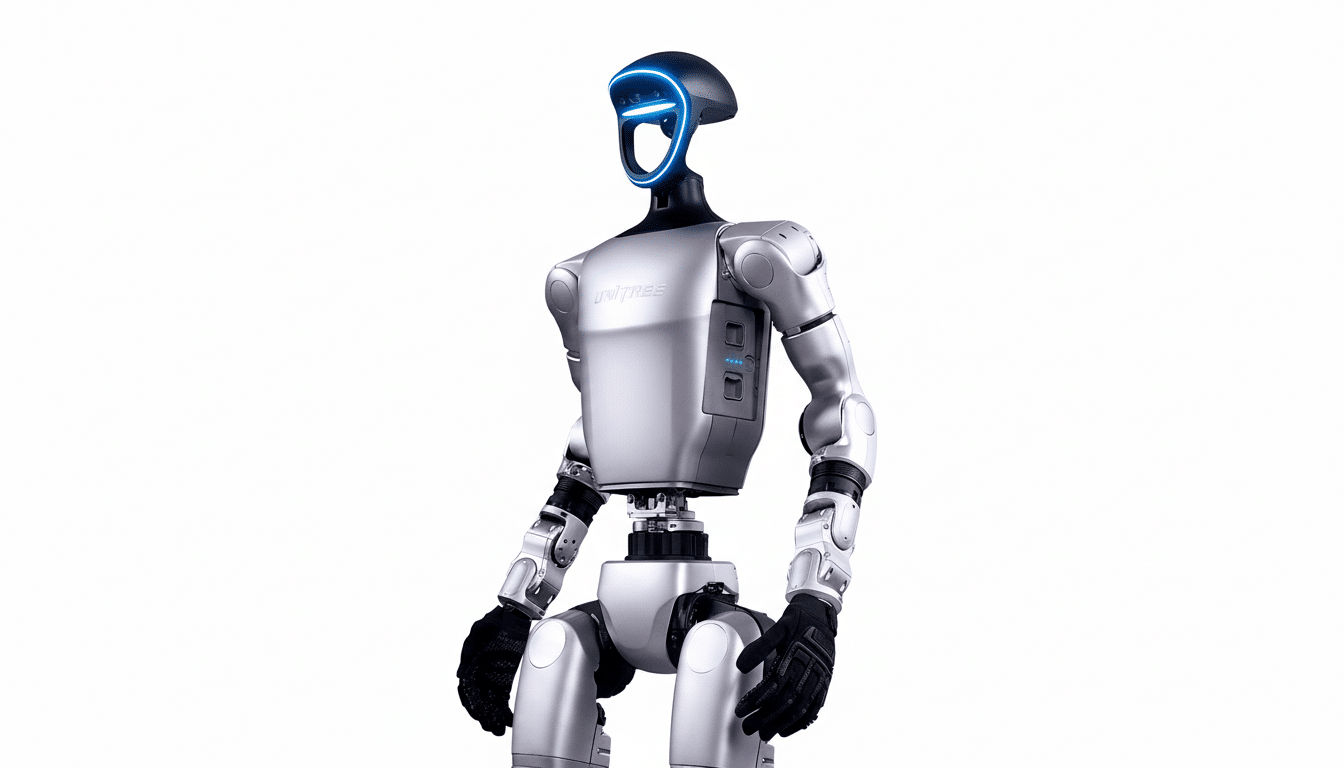

Commercialized humanoid robots have been used as vessels for broadcast by spoken commands, and to pass on this infection to other machines in the vicinity of the original units. A group of cybersecurity researchers from the Chinese hacking community called Darknavy[1] demonstrated at GEEKcon in Shanghai last month that they could hack a Unitree robot via its AI-enhanced on-board computer, then leverage a remote backdoor into the device to carry out an attack and command it to spread the infection wirelessly to another nearby unhacked robot, which was not even connected to the internet. The crew concluded the demo by commanding a robot to hit a mannequin on stage.

The Chinese proof-of-concept, reported by Yicai Global and showcased on Interesting Engineering, underscores how voice interfaces and networked autonomy can intersect in potentially hazardous ways. What used to seem like futuristic sci-fi peril now exists on the shelf in platforms marketed for research, logistics and personal assistance.

How the voice-command attack on humanoid robots worked

The hacked robot, the researchers explain, used an internal AI agent for interpreting voice instructions and then prompting higher-level behaviors. By exploiting a software vulnerability in that decision layer, they escalated their privileges and gained the ability to run any commands they wanted on the robot once it was connected to a network.

From there, the team used short-range wireless—think peer-to-peer connections like ad hoc Wi‑Fi or Bluetooth—to move the payload laterally to another robot close enough for a connection. Seconds, not minutes, counted between hops, as close proximity and default radio settings carry the potential to escalate from a single-device compromise into a local outbreak.

Importantly, the lure was audio. “The trust model of voice-controlled pipelines is fundamentally different from that of most conventional applications — this is in part because you have to ‘trust’ the devices not to activate and record your conversations,” Or Vingel reckons. “However, once the chain starting with wake-word detection and continuing on to the processing stack, TTS (Text-to-Speech) engine and ASR (Automatic Speech Recognition) is compromised, an attacker can manipulate or otherwise control audio content such that any skill can be activated.” And without strong authentication and guardrails between perception and actuation, spoken words can turn into direct control.

Why this exploit matters for safety and real-world use

For years, cybersecurity has revolved around the theft of data. Humanoid robots add kinetic risk. If robots are serving growing senior populations or retail and warehouse automation, an attacker no longer has to exfiltrate anything in order to do damage — they can manipulate motion, tools and doors. What was fit for the stage might, in less-constrained circumstances, result in collisions and property damage or injuries.

As many as 4 million industrial robots are deployed worldwide, according to the International Federation of Robotics, with a rapidly expanding network of service and mobile robots. Humanoids are still in the primitive stage, but pilots are now live across logistics and manufacturing, and platforms from companies like Unitree and Agility Robotics are entering real-world trials. The larger the footprint, the bigger the attack surface.

What’s at stake is not just direct harm. Localized worms, travelers via radio, could break production lines, force facilities to lock down and drain fleets by causing unscheduled safe shutdowns. In critical infrastructure, even brief interruptions ripple outward.

Voice scams aren’t new, but robots raise the stakes

It has been the consensus for years in academic work that audio interfaces can be fooled. Researchers at Zhejiang University showed DolphinAttack in 2017, which used ultrasound frequencies that the human ear can’t register to issue commands to popular voice assistants. A team from the University of Michigan and the University of Electro-Communications in 2019 demonstrated that modulated lasers shone at a distance could deceive microphones in a study they called Light Commands.

Robot platforms introduce two compounding factors: physical actuation and autonomy. Many newer machines pipe natural-language input through large AI models that then plan complex actions. That lays a broad—and occasionally brittle—interpretation layer where prompt injection, spoofing, or escalation is an option if authentication and safety policies are not hardware-based.

Past audits reinforce the theme. For example, IOActive reported in 2017 on security flaws in a range of consumer and service robots (allowing remote command execution) — the year before Anliker. The pattern is clear: convenience comes first; hardening often comes later, sometimes not until there’s a public scare.

What manufacturers can do now to secure voice-controlled robots

- Segment safety from convenience. Your critical motion limits, your emergency stops and torque caps should live on independent safety controllers that are impervious to being overruled by the AI agent or by the application layer, even if voice input is taken over.

- Authenticate the human behind the words. Employ signed control channels, challenge–response flows for sensitive commands and speaker verification with anti-spoofing to resist replays and synthetic agents. Filter ultrasound and shield microphones against subsonic injections.

- Lock down radios by default. Turn off P2P discovery, mandate pairing in direct presence, and separate robot networks from IT. Think of robots as untrusted endpoints in a zero-trust model, and adopt least-privilege policies alongside ongoing monitoring.

- Red-team the full pipeline. Consider audio adversarial tests, local propagation drills, and recovery actions. Leverage known recommendations, such as the NIST AI Risk Management Framework, ETSI EN 303 645 for consumer IoT cybersecurity, and safety standards (e.g., ISO 10218 and ISO 13482) for robotic systems.

- Finally, design for failure. Dismantle a unifying vision of interfaces that don’t log all command origins, physically challenge high-risk motions, and make safe-mode recovery apparent to non-expert users.

Key takeaways from the humanoid robot voice-hacking demo

This demo revealed that a voice UI can be a front door to a humanoid, and that short-range radios can make one hacked object into two after just minutes. As robots leave labs and venture into public spaces, the security baseline must change from “keep the data safe” to “keep people safe,” with hardware-backed protections, authenticated commands and locked-down connectivity built in from day one.