The moniker “ice giants” may be due for retirement. A new analysis has a group of planetary scientists at the University of Zurich contending that Uranus and Neptune may contain many times more rock than previously assumed, throwing into question the notion that ice giants, which orbit mostly beyond Jupiter in our own solar system, are dominated by frozen water and other volatiles.

The interpretation reframes decades of thinking about the solar system’s middleweight planets, results published in Astronomy & Astrophysics show. Although the nomenclature “ice giant” was intended to denote a compositional contrast with the hydrogen–helium gas giants Jupiter and Saturn, recent interior models of these blue planets suggest that their bulk compositions are consistent with a phase space that also includes dominantly rocky layers shrouded by thinner envelopes of H2, He, and water-bearing material.

New Models Shake Up the Ice Giant Narrative

Instead of assuming planets are angelically layered with clear onion-like shells, the Zurich team made thousands of interior profiles and kept adjusting them to fit each planet’s mass, radius, and our measured gravity field strengths. Importantly, all candidate structures had to satisfy realistic equations of state for materials under such extreme pressure and temperature conditions—from high-pressure water phases to silicate rock and metallic cores.

The outcome is not one “right” composition but a family that all agree with the data. Some habitable interiors may look like the classic water-rich picture. Others are rock-rich, with water and hydrogen–helium blended over great depths instead of being layered in tidy shells. The take-home message is sobering: to avoid assuming that both planets are made up primarily of ice, we need more data than current constraints can offer.

Lead author Ravit Helled and colleagues say that the lesson goes far beyond two planets. If Uranus and Neptune harbor multiple interior plans, then so do the countless sub-Neptunes we now have on record from missions like Kepler and TESS. Trying to tell what’s inside based on mass and radius alone is an inherently degenerate problem.

Clues, Tucked in Gravity and Density Measurements

There are already basic stats hinting at the ambiguity. Uranus has an average density of about 1.27 grams per cubic centimeter; Neptune’s is about 1.64. Those figures don’t definitively require ice-dominated interiors—particularly when rock and water might be all mashed up into lighter gases under megabar pressures.

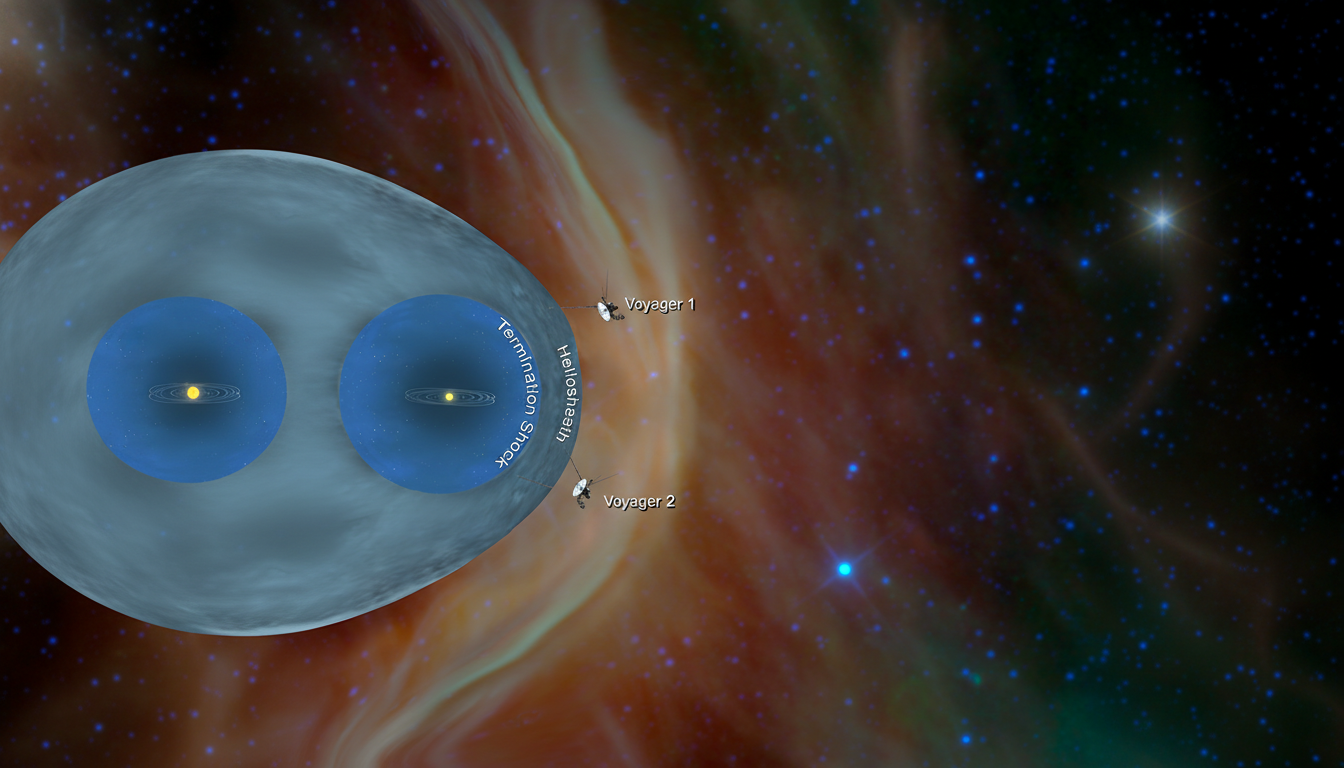

The most informative constraints come from the planets’ gravity fields, measured during Voyager 2’s only close flybys of each. Both water-heavy and rock-rich configurations can match those gravity harmonics—the fingerprints of how mass is distributed inside. Throw in uncertainties over rotation rates and the possibility of general differential rotation, and the picture is more flowing than textbook cutaways would have it.

Magnetic Oddities and Superionic Water Explained

One enduring mystery has been the wild lopsidedness of the pair’s magnetic fields, which are tilted by about half a right angle and offset from the planets’ centers. The new models lend support to a plausible suspect: deep layers of electrically conducting, churning pockets of exotic phases of water called superionic or ionized water, mixed with hydrogen and helium. The multilayered domains would be ideal for housing planetary dynamos, which naturally generate lopsided, multipolar magnetism—a scenario that matches the spacecraft and ground-based observations.

Curiously, the models indicate that Uranus probably sports a little thicker outer envelope of hydrogen and helium compared to Neptune—the dynamo-generating region of Uranus’s core may also be buried just a tad deeper. It is subtle differences like these that may explain why the two planets, which are roughly of equal size and mass, can be so different in atmosphere and magnetism.

Formation and Migration Reconsidered for Ice Giants

So if rock really does make up a greater share of their interiors, that changes the story. Rock-rich cores are more easily constructed closer in to a young planetary system, where solid silicate material is plentiful. The new work thus adds heft to the notion that Uranus and Neptune could have formed closer to the Sun and then traveled outward, a story line consistent with leading dynamical predictions of the early solar system.

The impact for exoplanet science is more immediate. Some other similarly composed worlds classified as sub-Neptunes could be just as compositionally diverse, with thinner-than-assumed water layers or dominantly rocky planets beneath modest gas envelopes. The Zurich team took a different tack, one that let data, not preconceptions, sculpt the interior architecture, and it provides the outline for more circumspect interpretations of alien worlds.

What It Will Take to Find Out for Certain

Definitive answers require new missions. A dedicated Uranus orbiter and atmospheric probe has already been prioritized as a top priority for planetary exploration by the National Academies’ decadal survey. A mission like this, crafted by NASA and perhaps international partners, would measure tiny changes in the gravity field, map magnetic structures over time, and sample directly from the atmosphere to pin down heavy-element abundances as well as cloud chemistry.

Laboratory experiments will need to do the same. Experiments to condense water, ammonia, and rock-forming minerals at pressures and temperatures matching those deep in these planets—supported by state-of-the-art quantum simulations—will refine the equations of state on which all interior models rely.

For now, the ice giant designation lives as a convenient nickname, not a chemical judgment. The developing picture is richer: Uranus and Neptune are complex, layered worlds in which rock, water, and gas intermingle under extremes—more geologically diverse, and more relevant to how planets form, than their nickname ever suggested.