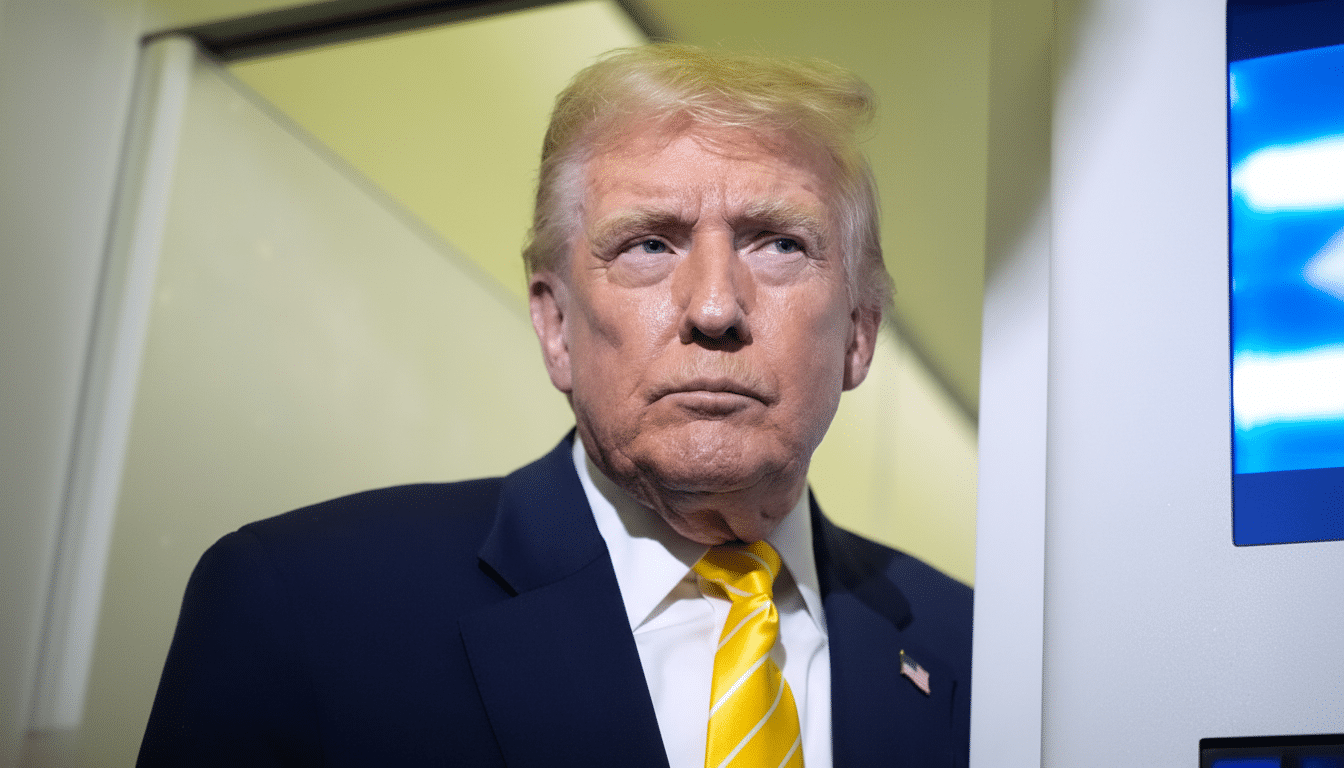

President Donald Trump said he would sign an executive order to block local governments from adding legal roadblocks to setting up artificial intelligence systems, declaring that there was not a reason “for the United States to fall behind” China and other countries in maintaining AI leadership even as Republicans and Democrats push back against sidelining local authority. The actions set up a high-stakes confrontation over who sets AI policy in the United States, and to what extent the White House can push forward with its own plan without backing from Congress.

What the Executive Order on AI Would Actually Do

A draft that has circulated in Washington would establish an AI Litigation Task Force to file lawsuits against state AI statutes, direct federal agencies to scrutinize “onerous” state regulations and encourage the Federal Communications Commission and Federal Trade Commission to promote national standards designed to override conflicting rules. It would also elevate a leading venture capitalist, David Sacks, to one of the highest ranks in AI policymaking and narrow the traditional role of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy.

An executive order, though, does not in and of itself preclude state law. According to the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution, broad preemption generally requires an act of Congress or a valid federal regulation with statutory basis. The order’s concrete course seems to be twofold: nudge agencies to write rules asserting preemption where Congress has delegated power and mount Dormant Commerce Clause challenges, arguing that a state-by-state patchwork unduly burdens interstate commerce. Both of those strategies would very likely be challenged immediately in court.

Supporters in the tech industry argue that a single national standard would provide companies with clarity and allow for faster deployment of cutting-edge models. Critics on both sides of the aisle counter that a sweeping preemption push — especially one undertaken by executive action rather than legislation — amounts to federal overreach and threatens to erode basic consumer and worker safeguards just as AI risks come into view.

Why States Stepped In to Regulate Artificial Intelligence

As Congress falters on guardrails, states have filled the vacuum.

- Tennessee ELVIS Act aims at preventing unauthorized AI voice cloning of artists.

- Colorado passed a first-in-the-nation law on “high-risk” AI systems, mandating risk management, testing and notice to consumers.

- New York legislators have introduced the proposed RAISE Act in an attempt to deter misleading AI in hiring and consumer interactions.

- California: A leading indicator. As the old saying goes, as California goes, so too goes the nation — and maybe the world. Thus it has behooved us to pay close attention to expectations in San Francisco, where there is an ongoing debate over safety and transparency mandates following a rash of AI bills in recent years.

The National Conference of State Legislatures has tracked hundreds of AI-related bills in nearly every state over the past two years, including dozens that passed. Most of the bills put specific emphasis on abuse of deepfakes, election integrity and how consumers are disclosed to when engaging with bots, as well as sector-specific uses like health care or financial services. Local officials and governors also point to infrastructure concerns, noting that data centers’ power and water demands are enormous while questioning whether jobs will be displaced.

Bipartisan Pushback Against Federal Preemption

Congress has consistently rejected broad preempting provisions. An effort to graft sweeping state preemption onto a must-pass defense bill recently failed, and another proposal for essentially freezing state AI lawmaking for a decade was overwhelmingly defeated in the Senate. Republican officials who normally promote deregulation have cautioned that reducing states’ police powers would be a mistake, though Democrats are pressuring them to instead encourage local experimentation as new threats emerge.

The attorneys general of over 35 states have warned federal lawmakers not to pass a bill that would override state AI laws, describing preemption as “disastrous” for consumer protection. More than 200 state legislators signed a similar open letter. The rift extends to industry: Some AI builders and venture backers — a category that now includes some of the dominant suppliers of models — have called for a single federal framework in order to avoid conflicting obligations; others in enterprise and creative industries back minimum national standards, preserving room for stronger state rules.

The Stakes Over Innovation and Safety in U.S. AI Policy

Trump contends that a single federal regulation is needed to keep America out front in the world’s AI arms race. From the Stanford AI Index, we know that America leads in leading-edge models and private investment in AI specifically — tens of billions are finding their way into American AI startups as well as infrastructure. Business groups caution that a “maze” of state requirements could slow deployment and spur research overseas.

But the harms that prompt state action are not theoretical. Robocalls and deepfake videos have impersonated public figures during the election season. Families and banks have been victims of voice-cloned scams. The FTC has noted record levels of losses to digital fraud, and law enforcement agencies have announced a rise in AI-abetted impostor scams. Practitioners and researchers have also reported problematic cases of chatbot interactions, further crystallizing calls for transparency, testing and accountability. NIST’s AI Risk Management Framework has become a baseline, but it’s optional.

What Comes Next in the Legal and Policy Fight Over AI

So, signed as described, the order would invite immediate litigation. Any claim of broad preemption will probably be challenged by states, which will contend that consumer protection, privacy and public safety are traditional state realms. Agencies would have to anchor such preemptive standards in statutes, creating an uncertain shoehorning of AI’s cross-sector use cases for yet more suits that might narrow or block the rules.

Near term, companies face a double reality: possible federal action that could move the country toward harmonization and a live, burgeoning set of state obligations. Many are already embracing “highest common denominator” compliance — employing risk assessments, tools to verify the provenance of media, strong human oversight and incident reporting — consistent with NIST guidance and some aspects of Colorado’s and Tennessee’s laws. Unless Congress passes robust AI legislation, the battle over “one rule” versus state experimentation is likely to end up in court — one injunction at a time.