The Tea, the viral app that promised women anonymous reviews of men and crowdsourced “receipts,” shot up to No. 2 on the charts before Apple removed it from the App Store. Coupled with the sprawling Facebook groups Are We Dating The Same Guy, a new reality has emerged: dating is being adjudicated in public, with screenshots as evidence and comments as subpoenas.

A Viral App Hits a Wall Amid Security and Moderation Fears

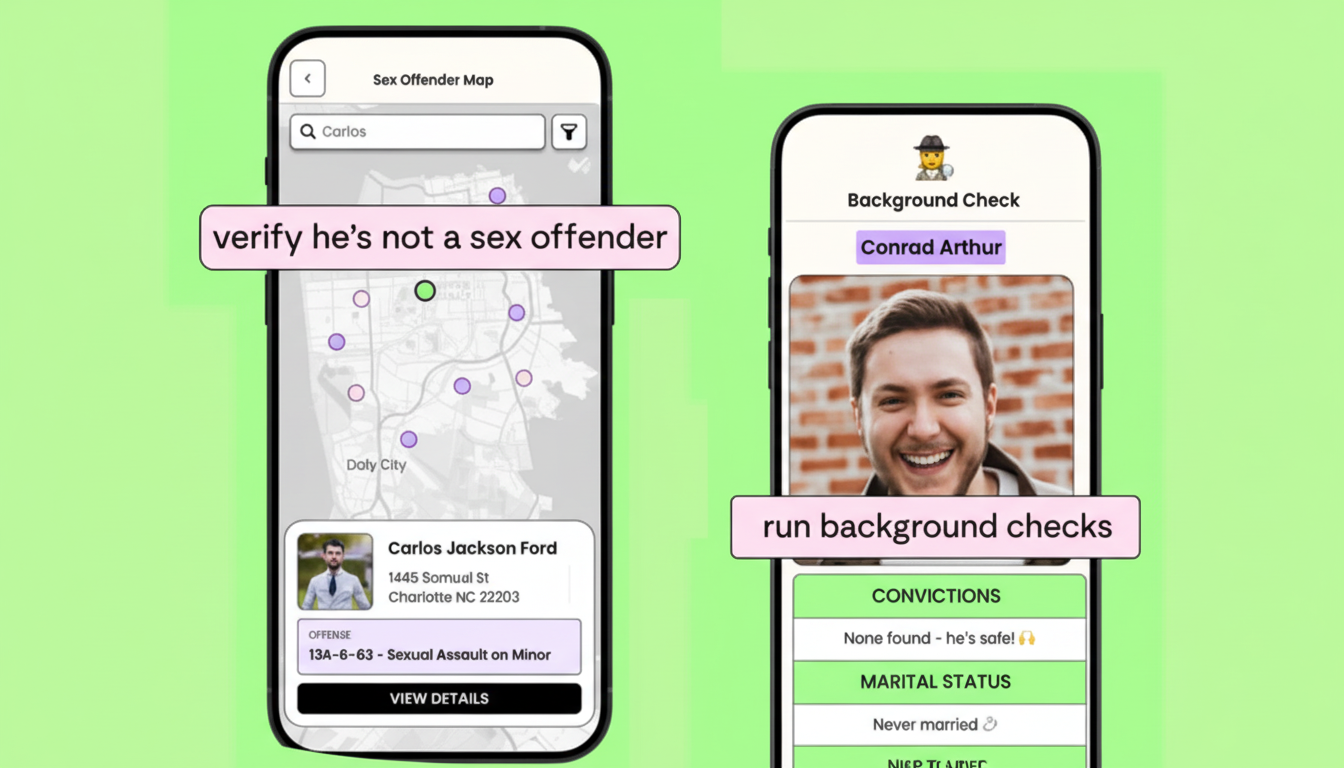

Created to enable users to post evaluations, authenticate identities with photo checks, even run background searches, The Tea was said to have quickly built a user base of more than four million people. Its rise was clouded, however, by two high-profile security incidents that fueled concerns about data protection and content moderation. Apple’s decision to pull it worldwide underscored the stakes for platforms that hosted such sensitive, user-generated allegations.

- A Viral App Hits a Wall Amid Security and Moderation Fears

- From Whisper Networks to Searchable Files

- Safety Gains and the Data Gap in Online Dating

- The Legal and Ethical Minefield of Searchable Allegations

- The New Courtroom of Dating and the Reputation Verdict

- What Better Guardrails Could Be Like for Safer Platforms

- The Bottom Line on Evidence, Due Process, and Security

The app is founded on a simple philosophy: Make private warnings discoverable. But when allegations are easily searchable and stick around, the line between community safety and reputational ruin shrivels quickly — especially when moderation is based on speed, not sworn evidence.

From Whisper Networks to Searchable Files

Are We Dating The Same Guy began as city-based Facebook groups in which women, who were admitted after vetting, posted to ask if others were dating the same man or post red flags. Screenshots were prohibited, confidentiality enforced and posts tightly moderated. Apps such as The Tea industrialize that idea, perpetuating the ephemeral whisper network into a durable, indexed dossier capable of surviving any breakup.

That permanence is the feature — and the peril. A misread text can go as viral as evidence of serious transgression, and the internet has too good a memory.

Safety Gains and the Data Gap in Online Dating

The appeal isn’t abstract. People notice overlapping relationships within hours, revealing patterns of coercive control, or hear about the time he had a restraining order taken out against him in the past — a history that never surfaces on his dating profile. Now that online dating is so popular, there’s a safety component you can’t afford to overlook — letting your friends know what you’re doing, and using crowdsourced information, such as the Girlfriend Collective map when it goes live, as a supplement to the vetting tools built into the platforms themselves.

There is a real risk environment out there. Pew has found that women are far more likely than men to believe online dating is a dangerous way to meet someone, and the Federal Trade Commission estimates that victims of romance scams lost $1 billion over the last year. Community vetting can be a time- and harm-saving process, especially when formal reporting routes seem slow or inaccessible.

The Legal and Ethical Minefield of Searchable Allegations

Turning unsubstantiated claims into something that could be searched by others creates legal and ethical quandaries. In most cases, accusations of criminality or infidelity are actionable per se. And whereas the legal shields available to companies that host false information can protect even giant platforms, individual posters have no such protection — and no matter how clear the law may be on your side, actually correcting a viral lie is very expensive.

There are bias risks, too. Community threads can reflect racial stereotyping, homophobia, even slut-shaming under the umbrella of “safety.” And weak evidence standards lead to more: tiny offenses of etiquette — lazy repartees, clumsy exits — may be confounded with abuse, distracting from the genuinely dangerous.

The New Courtroom of Dating and the Reputation Verdict

The result is a parallel justice system. The charges are screenshots, the courtroom is a feed and the verdict is social reputation. For some, this punishment is long overdue. But for others, it fosters anxiety, with people dating as if under scrutiny and interpreting normal shortcuts and missteps as indictments. The dynamic can congeal distrust among strangers at the exact moment connection calls for a presumption of good faith.

What Better Guardrails Could Be Like for Safer Platforms

If these platforms remain — or if another (or others) take their place — the way forward is stronger guardrails. Digital rights and victim advocacy experts say some baselines are clear: identity verification for reviewers; obvious lines in categories between criminal conduct and “bad date” complaints; an opportunity to respond, as well as fast takedown paths for any contested claims; moderators who are trauma-informed and trained to identify coordinated harassment.

And security has to be nonnegotiable: third-party audits, minimal storage of data with high levels of encryption for sensitive uploads and granular permissions for sharing. Transparency reports on removals, disputes and outcomes could be used by users to measure reliability. Finally, algorithms should downlevel unprovable etiquette rants versus well-documented safety alerts — and give low-severity posts an expiration date, so that the stigma is not forever.

The Bottom Line on Evidence, Due Process, and Security

Apple’s takedown is not the end of “receipts culture” in dating; it’s a stress test on how reputation systems should function. The people don’t want a mob, they want protection. If platforms can make the pivot toward evidence, due process, and security at the center while retaining the community care that made these networks appealing, it is possible for them to mitigate harm without sending every breakup into an ad hoc bench trial.