T-Mobile is accusing AT&T of making its own customer experience worse by blocking logins from the T-Life app in an escalating high-stakes fight over a new plan-comparison tool that’s meant to make switching carriers a little less painful. The fight has also migrated out of the product category and into the courtroom: AT&T sued T-Mobile, accusing it of data scraping, and Verizon was reported to have taken a similar step in locking down the tool.

What triggered the clash over T-Life comparisons

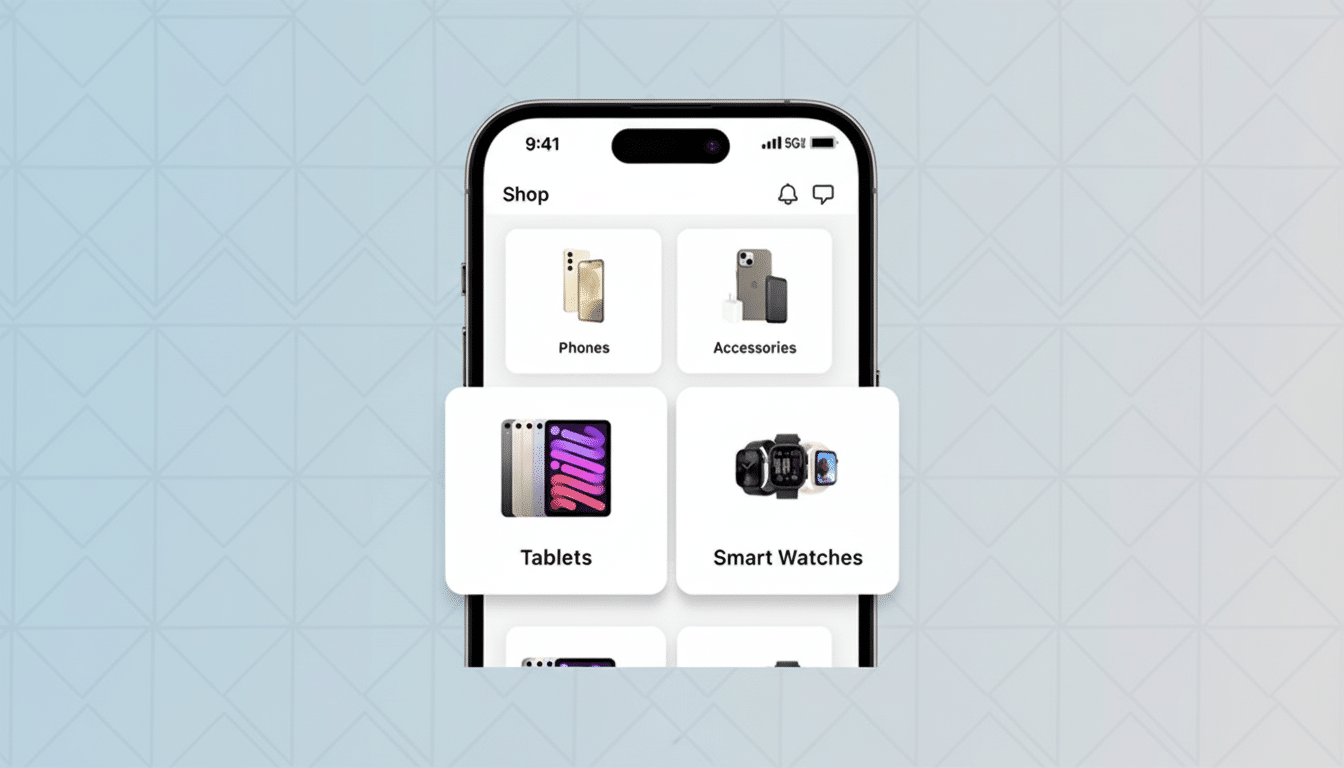

T-Mobile’s “Switching Made Easy” is part of the T-Life app, and it will dissect an existing AT&T or Verizon account to suggest a similar (in terms of service) T-Mobile plan and promos.

- What triggered the clash over T-Life comparisons

- AT&T lawsuit and scraping accusations against T-Mobile

- T-Mobile’s counterpunch centers on choice and data access

- The data portability problem at the heart of this dispute

- Right now, what this means for customers using T-Life

- What to watch next in the carriers’ escalating dispute

The pitch is straightforward: Sign into your current carrier through T-Life, get a like-for-like quote, and then see if the grass is greener elsewhere. But now, says The Mobile Report, both AT&T and Verizon have begun blocking those logins — shutting the door on users before T-Life can pull any data.

T-Mobile positions the product as a win for the customer first and foremost — pun intended. The company says users opt in to share their account info for personalized recommendations, and that the tool simplifies confusion caused by the industry’s maze of line credits, device promos, and taxes-in pricing. Halting T-Mobile’s sign-in journey, T-Mobile contends, hurts customers by making it more difficult to compare offers that they do already qualify for.

AT&T lawsuit and scraping accusations against T-Mobile

AT&T has gone beyond technical blocks and sued, accusing T-Mobile of building a bot to scrape customer-account pages and even fine-tuning it on multiple occasions in order to stay under the radar. In materials it shared with reporters, AT&T contended that the T-Life bot scrabbled for far more data than needed, scraping some 100 fields, and tried to disguise itself as an end-user session.

AT&T says it sent a cease-and-desist and the scraping activity stopped on its site. If not, T-Mobile compiled the tool to request an upload of a PDF bill or manual inputs in order to keep the comparison feature running. AT&T also is said to have informed Apple, which has claimed the practice runs afoul of App Store rules, but T-Mobile insists it’s in compliance with platform policies. Apple has not taken a public stance.

T-Mobile’s counterpunch centers on choice and data access

T-Mobile’s argument is all about choice for consumers and access to data. The carrier is arguing that if a customer opts to log into T-Life rather than sign up for the cheaper deal, then they’re exercising their right to use their own data for determining which competing offers are being presented. In T-Mobile’s view, AT&T is “actively breaking its own digital experience” by blocking legitimate logins and preventing account holders from using a service that they authorized.

More broadly, the company portrays the pushback as resistance to competition. If you make people screenshot a PDF and call to compare plans, fewer will change. That friction serves incumbents, not consumers, and erodes the product’s promise to reduce the time and guesswork that goes into moving service.

The data portability problem at the heart of this dispute

The legal debate is about where permissive behavior stops and unauthorized access begins. Page scraping of authenticated pages has always been in a bit of a grey area. Banking has solved for this conflict with tokenized APIs in open banking structures, which replaced password-sharing robots with secure data pipes. There’s no comparator in U.S. telecom, so carriers and apps make it up as they go along, with each fight extracting a cost, if not clarity, from the courts.

Consumer advocates argue for more portability and transparency under the Federal Communications Commission’s principles to help prevent impediments toward switching. Privacy laws like California’s CPRA are about consumer data access; yet they’re also not exactly a guarantee that third-party bots get unfettered access to private portals. There are no common carrier-grade APIs for billing and plan data, so cluttering the web with contested scraping becomes the least unattractive approach.

Right now, what this means for customers using T-Life

For customers trying to shop for plans within T-Life, the immediate impact is more manual labor. Several are being asked to upload a recent bill PDF or type in key details rather than going through a simple sign-in. That still activates the estimated savings, but it loses the success of an immediate and shrug-free account pull directly — particularly for multi-line families with device payments and credits.

Switching itself is not blocked. Number porting is still covered by FCC rules, and eSIM has made activating easier on compatible phones. The friction is in finding and vetting. All the research from industry analysts and customer-care studies show that digital simplicity is a powerful churn driver, which is why all three national carriers invest heavily in app-based onboarding and support.

What to watch next in the carriers’ escalating dispute

Among the key flashpoints expected are how the court factors scraping claims in with customer consent; whether Apple is dragged into app activity; and, well, if Verizon takes its own legal path.

The greater leap would be an industry shift toward standardized, secure data sharing for switching and comparing bills, akin to financial aggregators in banking. Short of that, look for more tug-of-war over who is in charge of the login screen — and, by extension, in charge of the customer journey.

In the meantime, T-Mobile will continue to rely on uploads and manual inputs for billing information to power its pitch, while AT&T and Verizon make their portals more difficult. The result could help establish where the limits are to what authorized third-party apps can do in carrier ecosystems — and how much control customers really have over the data they bring with them to their respective tables.