Stoke Space has just raised a $510 million Series D, a monstrous sum for a launch startup that hasn’t yet made it to orbit.

The headline number is the attention-grabber; the lead investor is what tells us what’s really happening. The round was led by U.S. Innovative Technology, Thomas Tull’s fund built to back national-security-critical tech. That decision says plenty about where launch is going: defense first; everything else, second.

For a decade, investors were informed that commercial satellites would be the flywheel for new rockets. Reality has been less forgiving. SpaceX’s low prices and frequent launches soaked up almost all the commercial demand, leaving barely any oxygen for others to get a foothold. Defense, on the other hand, is ramping up and paying for resiliency, responsiveness, and redundancy — exactly what emergent launch providers promise.

Defense is the new center of gravity for launch

Geopolitics reshaped the market. The war in Ukraine, the slow but steady maturation of Chinese space capabilities, and the acceptance as “normal” of space-based targeting shifted launch from a tech curiosity to a strategic requirement. The Pentagon is developing layered architecture for missile warning and tracking while hardening communications and navigation — efforts that require a faster, more diverse launch base.

Programs are following the rhetoric. The Space Force’s National Security Space Launch Phase 3 made more competitors eligible with the Lane 1 track, which invited new vehicles to vie for launches worth up to $5.6 billion over a decade. The Space Development Agency’s proliferated LEO constellation needs regular, predictable service. The Pentagon’s cyber missile-defense modernization, which is often referred to as a layered “dome,” is enlisting suppliers from throughout the industrial base.

Speed is the watchword. Strategically responsive space demonstrations — such as Firefly’s rapid-turn (years to days) Victus Nox mission with the Space Force — demonstrated that hours-to-days are doable when all of the pieces — hardware, operations, and range support — line up. That pace calls for more launch options, not fewer, and it favors architectures optimized for rapid recycling and simple ground ops.

Why Stoke is a defense play in the new launch era

Stoke’s pitch is bespoke for that environment. The company is working on a fully reusable launch vehicle with a hydrogen-oxygen upper stage featuring the distinctive ring stage engine and focusing on rapid turnaround with minimal refurbishment. It flew a vertical takeoff and landing ‘hopper’ version to prove out reusability on the upper stage — a focus that most rivals delayed until after their main launch vehicle debuted. That emphasis is key to responsive launch requirements.

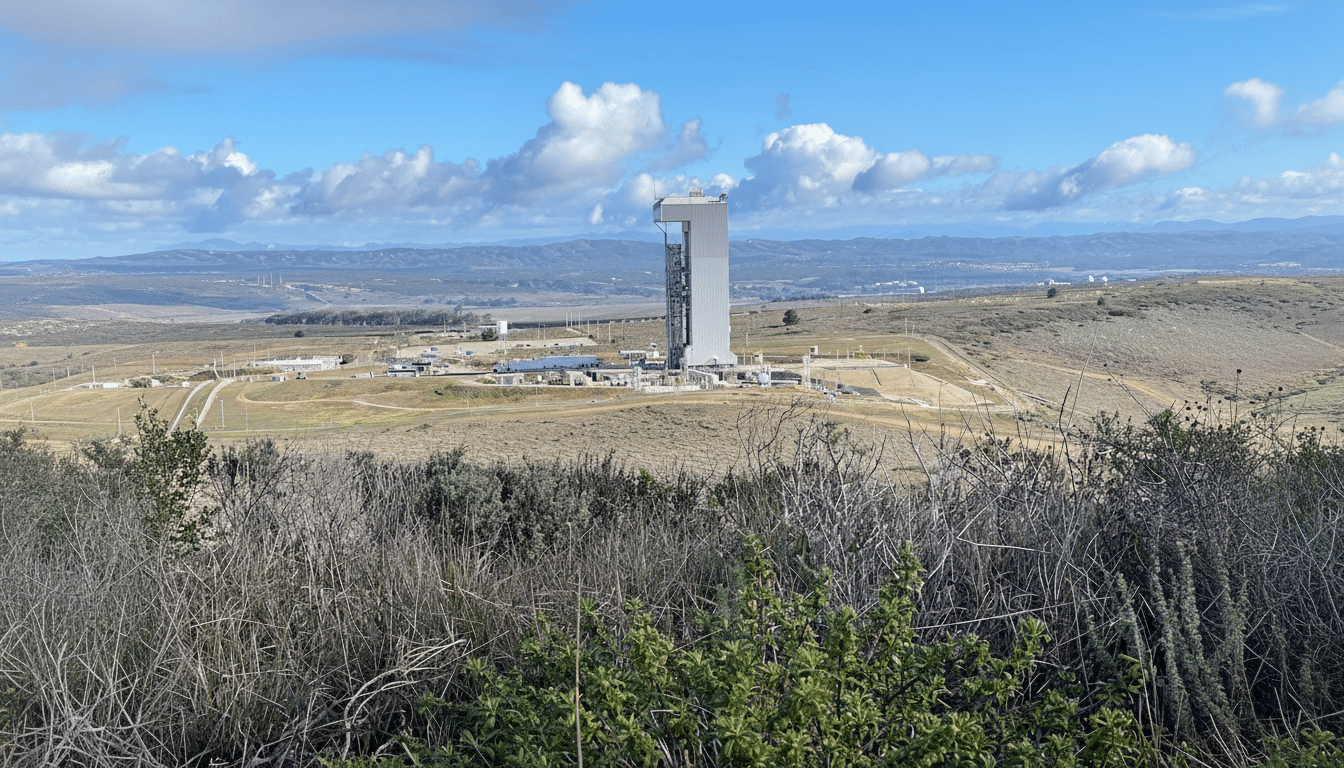

Being selected for NSSL Phase 3 Lane 1 provides Stoke a path to government missions if/once it demonstrates an ability to reach orbit and meet reliability requirements. The company also owns Launch Complex 14 at Cape Canaveral, placing it within the nation’s busiest military range. It has this new set of investors — ones with a pro-defense lean, such as Washington Harbour Partners and General Innovation Capital Partners — who are seeing capital aligned behind customers.

The lead investor matters too. U.S. Innovative Technology has supported companies like Shield AI and this month led a round in Gecko Robotics, betting on technology that adds to national resilience. The launch provider with the reuse-first mentality underscores that responsive, repeatable access to orbit is seen as critical infrastructure rather than a nice-to-have.

Commercial dreams, grounded by economic gravity

There remains a commercial market — broadband, Earth observation, data relay, and lunar cargo — but it is not infinite nor evenly distributed. SpaceX’s sub-hundred-billion annual pace, as well as its “vertically integrated” satellite business model, put crushing price and schedule pressure on the large manufacturers. It’s an arrangement that has prodded peers to tend increasingly to government work as their anchor source of revenue.

Examples abound. Rocket Lab’s backlog is heavily weighted toward civil and national security missions for NASA, the National Reconnaissance Office, and the Space Development Agency. Firefly’s $855 million purchase of SciTec was justified as expanding Firefly’s place in the defense market. Even Relativity Semiconductor’s sale under Eric Schmidt did not come without candid words about strategic competition and the need for domestic leadership in space and AI.

Capital is flowing accordingly. Industry trackers like PitchBook have logged record levels of activity in defense tech over the past two years as generalist funds adopt dual-use theses. In launch, this means investors perceive robust assured access to space, mission flexibility, and certification pathways as more valuable than speculative high-volume commercial manifests.

What to watch next for Stoke Space and launch markets

Three indicators will determine if Stoke’s raise turns into sustainable advantage:

- Orbital proof and repeat flights; reusability needs to transition from the test pad to a reliable cadence.

- Certification; crossing mission assurance gates for national security payloads releases higher-value task orders.

- Operations; actual responsiveness demands efficient range scheduling, rapid-turn processing of the ground systems, and a supply chain prepared to handle repetitive liquid hydrogen turnaround.

Policy and purchasing will be as important as propulsion. And if Space Force bakes responsive tactically applied launch into follow-on programs and SDA continues its rapid tempo of deployments, the market will value providers who can get a launch off quickly from multiple pads. If priorities of spending start to change, or if there is a certain acceleration of the consolidation we think may happen, only very differentiated architectures are going to be standing.

The larger picture is already evident. Stoke’s round is not so much a bet on a growing commercial backlog as it is an offer to become a part of the nation’s strategic space infrastructure. In the launch market of today, defense is not an adjacent opportunity — it’s the demand signal that decides who gets funded, who gets to orbit, and who survives.