Two of the most prominent space startups sent a pointed message to Washington from an industry stage overseas: make a decision on the next U.S. space station, and do it soon. Executives from Vast Space and Axiom Space urged NASA to lock in its Commercial LEO Destinations plan, warning that every month of delay increases the risk of a costly gap after the International Space Station retires.

Why the timeline for a new U.S. space station is tight

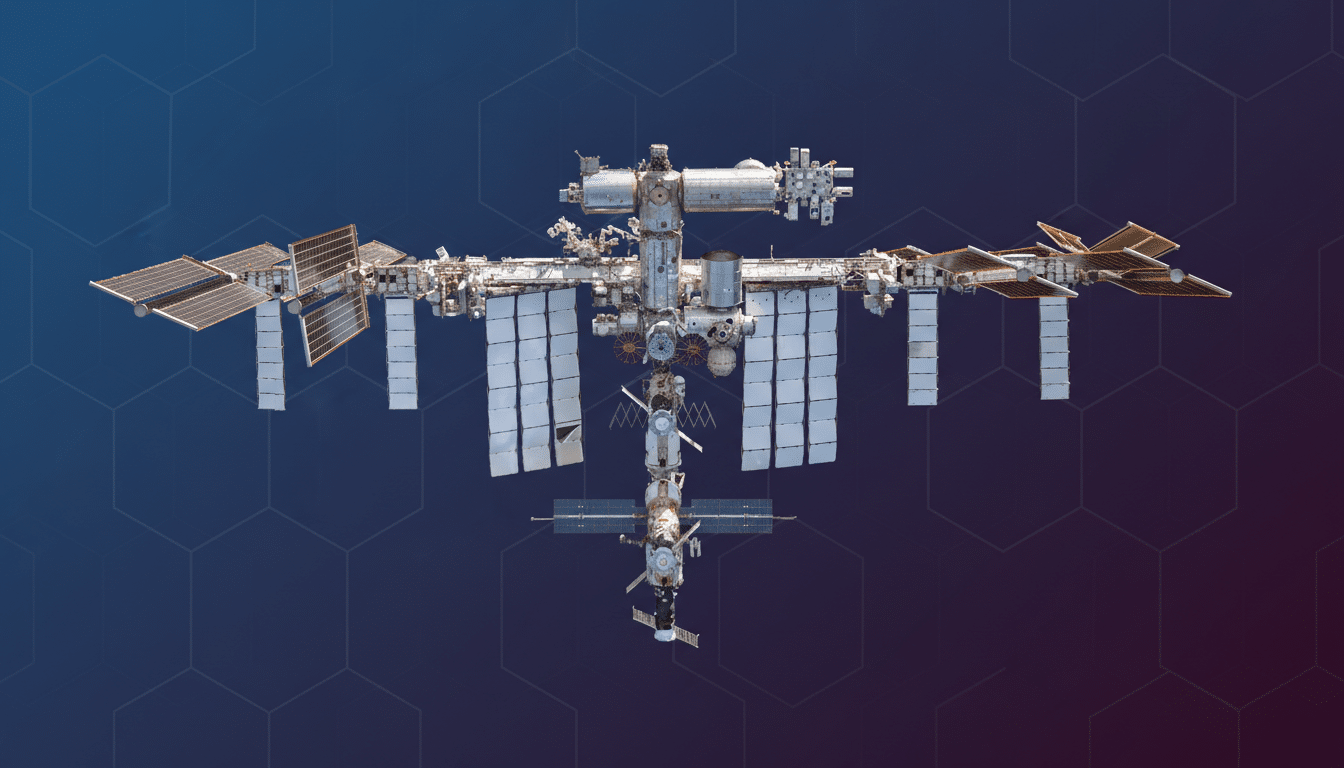

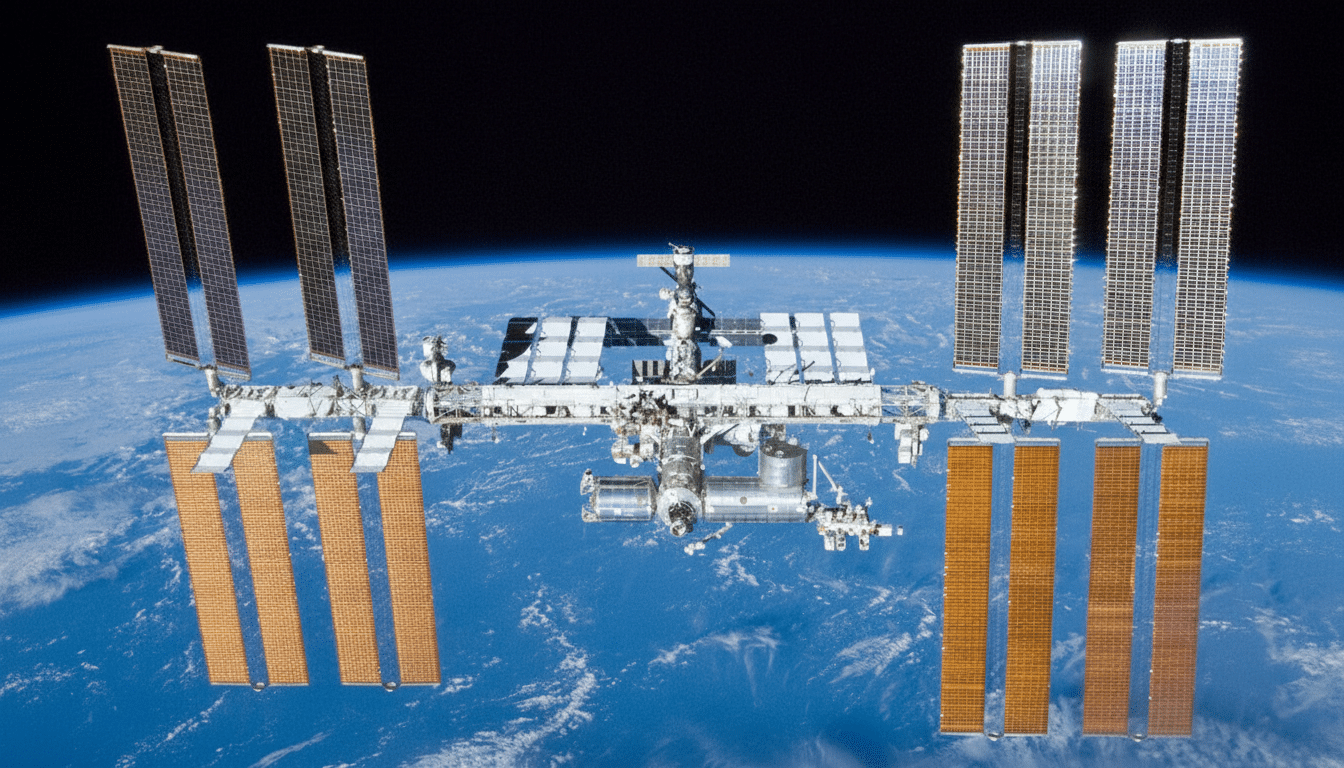

NASA intends to end ISS operations and conduct a controlled reentry around the start of the next decade, a move that will cap a quarter-century of continuous human presence aboard the laboratory. The agency has said it will transition to commercially owned outposts, acting as an anchor customer rather than the sole operator.

That transition demands a downselect, firm milestones, and sustained funding. Industry leaders say the current procurement for the next phase has been paused amid budget pressures. The Government Accountability Office has repeatedly flagged schedule risk, and NASA’s own Office of Inspector General has warned that overlapping operations—running ISS while at least one private station spins up—is essential to avoid a break in services and crewed access.

The stakes are not only technical. ISS operations cost NASA on the order of several billion dollars annually, according to OIG reporting, and an orderly handover is the only way to avoid paying twice for less capability. NASA is also procuring a U.S. deorbit vehicle to guide the ISS to a safe splashdown, adding another program that must be synchronized with the commercial station timeline.

Competing designs and business models for LEO stations

Axiom Space is pursuing a stepwise approach: launch its first modules to the ISS, build out a complex on orbit, then undock to form a free‑flying station. The company has emphasized a hybrid development model—building critical systems in-house, like life support, while sourcing pressure shells and other structures from established suppliers such as Thales Alenia Space. That approach can reduce technical risk but requires careful supply‑chain choreography.

Vast Space is taking the opposite tack: vertical integration and common parts, with an eye toward mass production. Its initial single‑module outpost is designed to launch fully assembled on a medium‑lift rocket, serving as a pathfinder for a larger, multi‑module complex. Vast has already flown a testbed spacecraft to mature avionics and propulsion, but, like others, has pushed back initial launch targets into the late 2020s as it de‑risks systems.

Two heavyweight consortiums round out the field. Blue Origin leads the Orbital Reef team, with partners including Sierra Space and Boeing, proposing a multi‑module, business‑park concept. Starlab, managed by Voyager Space with Airbus as a core partner, is pursuing a single‑launch station with European‑built habitation. Northrop Grumman, once a prime proposer, shifted to support the Starlab effort—evidence of consolidation as teams align around the most viable concepts.

All of the contenders talk up a similar revenue stack: government services, hosted research, in‑space manufacturing, and tourism. They point to pharmaceutical crystallization, semiconductor processes, and advanced materials like ZBLAN optical fiber as early commercial use cases, building on experiments already run on the ISS by firms such as Merck and Redwire. But robust demand will not materialize without NASA’s early commitments—crew time, cargo, and research—to anchor the market.

Avoiding another human spaceflight gap in low Earth orbit

Industry leaders are explicit about the geopolitical and capability risks. The United States experienced long gaps before: the six‑year lull between Apollo and shuttle, and the nearly nine‑year period after shuttle retirement when NASA relied on Russian Soyuz seats before commercial crew came online. Meanwhile, China’s Tiangong station is steadily occupied, giving Beijing uninterrupted momentum in low Earth orbit.

NASA’s Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel and GAO both caution that a gap in LEO presence would erode workforce skills, disrupt microgravity research, and complicate certification pathways for future deep‑space missions. An overlap period—where ISS operations taper while at least one commercial station ramps up—is widely seen as the only realistic way to transfer know‑how, validate systems, and keep crews flying.

What NASA must decide next to ensure a smooth transition

Companies say the priority is clear: downselect one or two providers, sign milestone‑based awards that resemble Commercial Crew, and publish a firm certification regime. Standardizing docking, power, and data interfaces will help keep options open while avoiding bespoke, non‑interoperable hardware. Just as important is committing to multi‑year services—crew time, cargo, and research—so providers can finance stations with credible revenue forecasts.

There’s room for competition even after a downselect; a second provider can serve as backup and price check. But there is little room on the calendar. Startup leaders say they’re prepared to accept a decision that goes against them if it means the United States avoids a lapse in orbit. The message from industry is blunt: pick a path, set the milestones, and let the teams build.