Ring set out to deliver a warm-and-fuzzy Super Bowl moment featuring a missing puppy, a tearful reunion, and a call to “be a hero.” Instead, the company ignited a bipartisan firestorm over surveillance in American neighborhoods. The new Search Party feature promises to scan nearby Ring cameras for a lost dog, but viewers quickly connected the dots: if the system can find a pet on a patchwork of private cameras, what stops it from being used to find people?

Why the Cute Dog Story Set Off Surveillance Alarms

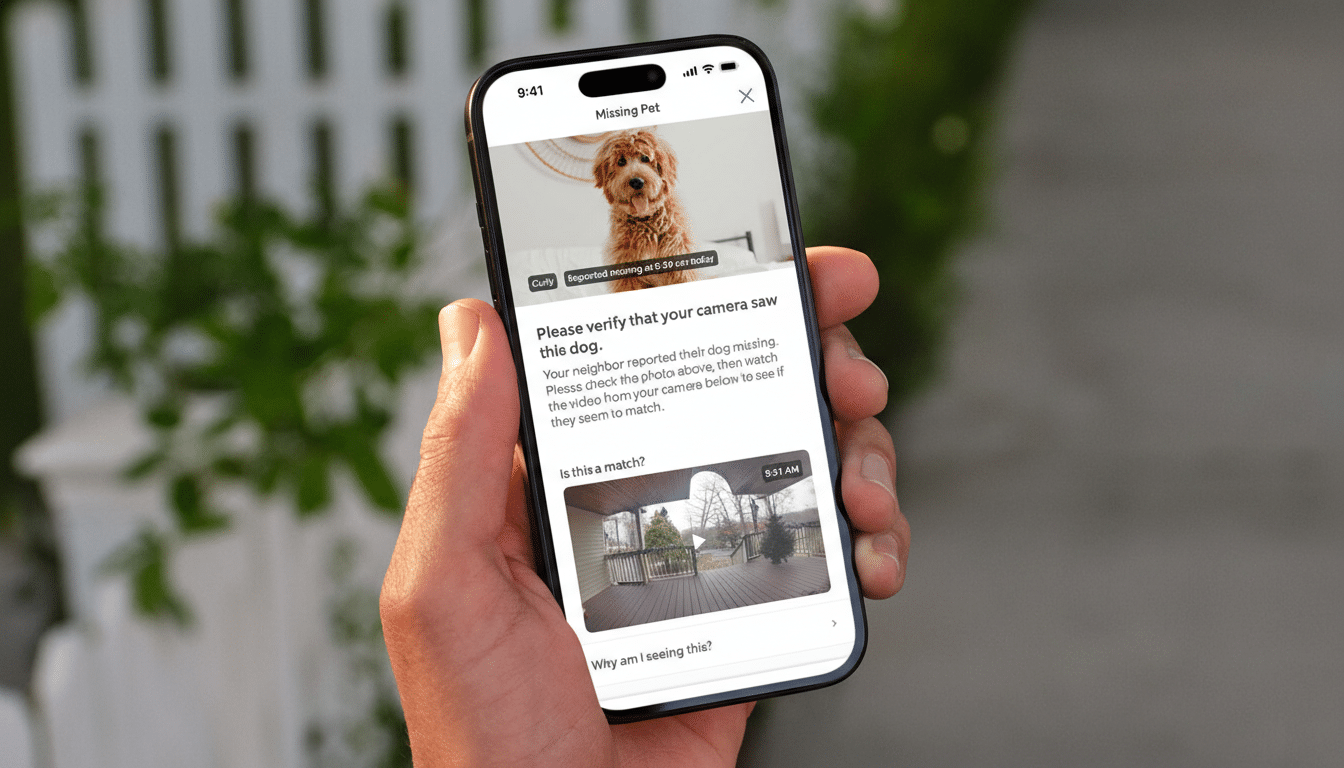

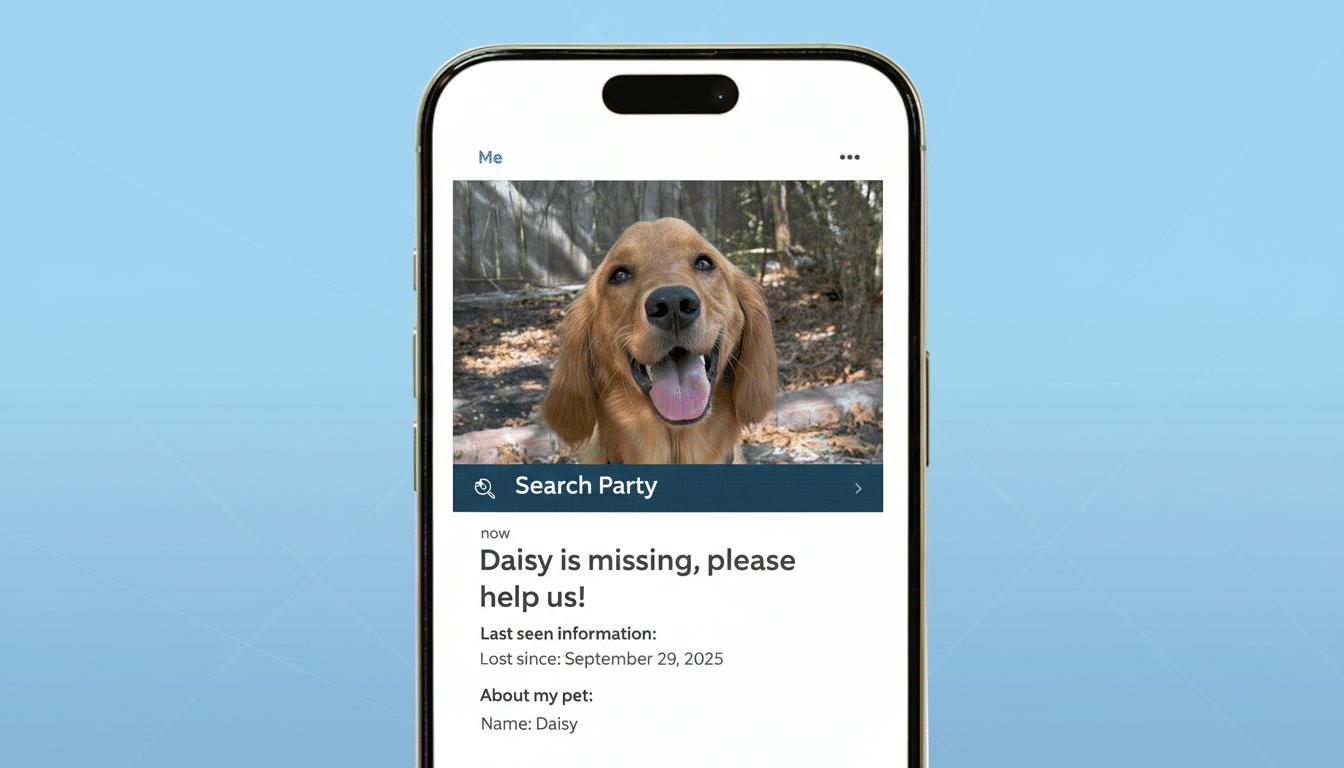

Search Party asks owners to upload a photo of a missing pet. From there, participating Ring doorbells and cameras in the area use AI to flag possible sightings. On paper, it’s a community service for anxious pet owners. In practice, critics see classic function creep—once a network learns to index and search for one class of object, expanding it to others is a policy decision, not a technical stretch.

That gap between intention and capability is what made the ad feel dystopian to many viewers. A neighborhood-scale visual search across privately owned cameras suggests a turnkey template for person tracking, whether by homeowners, bad actors, or authorities. Even people who love dogs bristled at the normalization of ambient surveillance dressed up as a feel-good moment.

The Privacy and Policing Context Around Ring

Ring’s track record looms large. In 2023, the Federal Trade Commission said Ring employees and contractors had improperly accessed some customer videos; Amazon agreed to pay $5.8 million to settle the allegations. Privacy groups like the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the ACLU have also warned for years that doorbell ecosystems create a de facto public–private surveillance grid that can be tapped by law enforcement.

Ring has adjusted its policies under pressure. The company says it shares videos with police only with a warrant, subpoena, customer consent, or in emergencies, and it ended in-app public safety requests for footage. But those safeguards don’t calm everyone, especially communities already wary of immigration enforcement. For them, a “lost dog search” looks less like a novelty and more like a test run for broader tracking.

There’s also a legal dimension. Illinois’s Biometric Information Privacy Act, along with biometric statutes in Texas and Washington, places strict conditions on collecting and using face data. While Search Party focuses on pets, advocates fear it could pave the way for person-identification tools that collide with state laws and civil liberties if the scope widens.

The Tech Reality Behind Pet Recognition Systems

Computer vision doesn’t draw moral lines—it detects patterns. A model that picks a specific dog out of thousands of frames can, with additional training and policy approval, be adapted to recognize human faces, clothing, or license plates. That’s why the ad rang alarm bells among technologists: it showcases the scale and coordination required for neighborhood-wide search, the hardest part of any identification system.

Accuracy and misuse risks compound at scale. Even a modest false-positive rate can create a blizzard of erroneous “matches” when spread across a city’s worth of cameras. And while pet-finding errors are benign, false human matches are not—wrongful arrests tied to facial recognition have already occurred, including high-profile cases in Detroit. Translating a pet tool into people-tracking heightens those stakes dramatically.

Public Sentiment by the Numbers on Surveillance

Americans are increasingly uneasy about data use. Pew Research Center has found that 79% of U.S. adults are concerned about how companies handle their personal information, and a majority doubt firms use data in ways that benefit consumers. Layer that sentiment onto the physical visibility of doorbell cameras—Parks Associates estimates roughly 17% of U.S. internet households have one—and it’s clear why the ad struck a nerve. The bigger the network, the greater the perceived risk of abuse.

The ad’s own boast that it helps recover lost pets daily backfired for some viewers. To critics, that frequency signals not just utility but normalization: the routine mobilization of a privately run visual tracking grid, turned on and off by a single company’s rules.

What Ring Says and What Viewers Heard Instead

Ring frames Search Party as strictly opt-in and limited to animals, and the company has said it does not use facial recognition in its consumer products. It emphasizes consent and legal process for any law-enforcement access. Those assurances matter on paper, but the commercial’s storytelling—neighbors rallying via networked cameras to locate targets—told a different, more sweeping story that many people simply didn’t trust.

Advertising lives or dies on subtext. In this case, the subtext was unavoidable: if finding a dog across dozens of doorbells is the feel-good baseline, what else could this system do when the stakes—or the requests—change?

A Super Bowl Snapshot of Tech Anxiety and Trust

The Search Party spot also landed amid a broader cultural jitteriness about AI. Another Amazon ad during the game leaned into dark humor about smart assistants gone awry. Together, the messages painted an uncanny portrait of helpful, omnipresent machines—useful until they aren’t—fueling the online backlash to Ring’s more earnest pitch.

That’s why so many people hated the ad: not because they oppose finding pets, but because the spot treated neighborhood-scale surveillance as heartwarming community spirit. For a public already wary of data collection, algorithmic bias, and the blurring of private and police video streams, the puppy didn’t soften the implications—it spotlighted them.