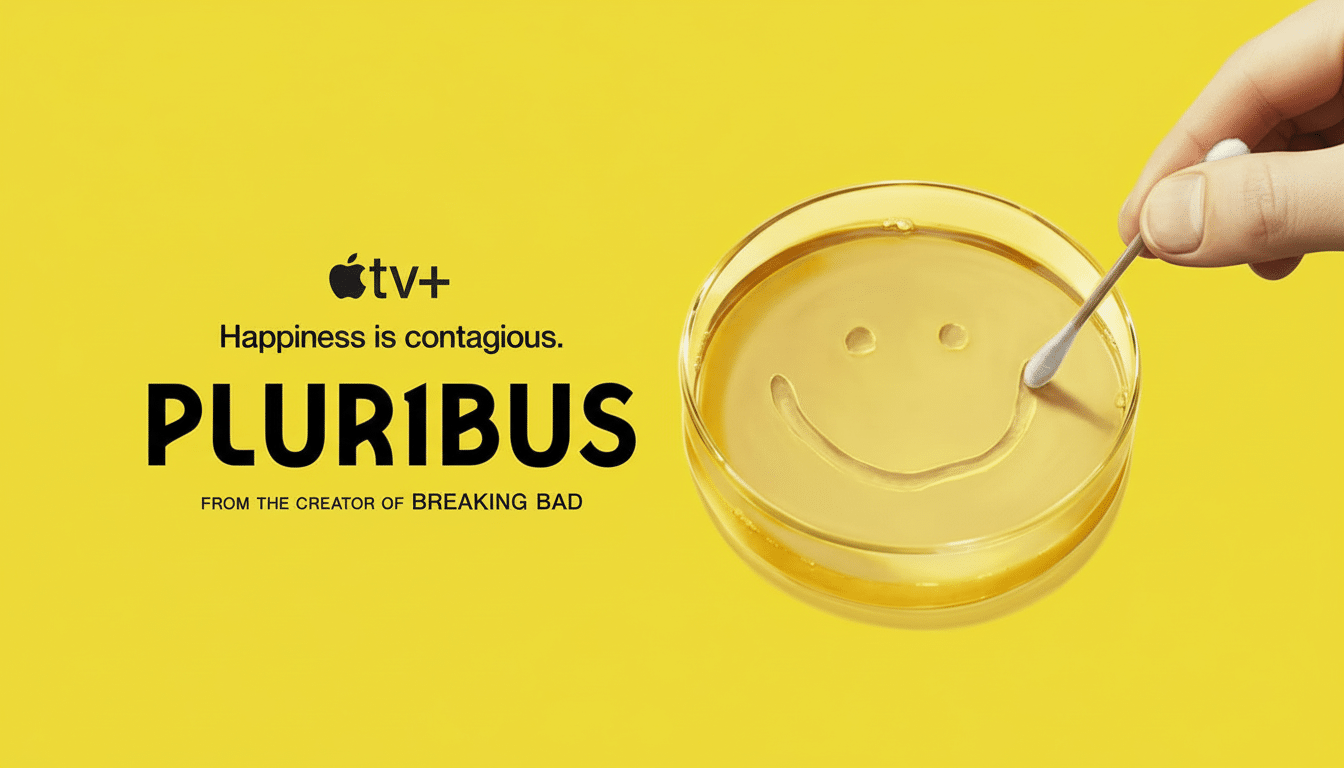

Vince Gilligan’s new Apple TV sci‑fi drama has raised an unexpectedly pressing question in many viewers’ minds: where are all the animals that should be in Pluribus?

The show’s “Joining” reduces most humans to a synchronized hive; dogs, cats, birds, and zoo creatures all but disappear from the frame—creepy hints instead of closure.

Clues the Show Has Already Given Us About Animals

Early episodes are breadcrumb trails. The agent has been tested on animals before a rat bite transmits it to humans, and that very lab rat shows the brief muscle-lock we saw in Joined people when Carol agitates them. A council of non-Joined survivors traveling on Air Force One reports “empty zoos,” and the Joined opened enclosures, releasing everything from giraffes to big cats—maulings too.

In the neighborhood, silence is louder. No pets skitter through doorways. No birdsong, no feral cats within sight of dumpsters. One character insists she “never took my dog off the chain”—but we’re never shown it. Meanwhile, Joined humans won’t kill animals or even insects, but will cook the meat they’ve already acquired (and are observed restocking supermarket meat cases—meaning it would appear they’re scavenging existing inventories, not adding fresh kills to the system).

How Animals Might Fit Within the Joining Collective

The series plays coy. That rat-level freeze is a sign that the agent has broader impact than on humans. The Joined claim they “cannot intentionally end life,” which may be a form of practical ethics—or the result of encountering nonhuman minds. If animals were part of the whole collective the way other microorganisms are, you might expect coordinated animal behavior: pets trailing chores or flocks and herds organizing with uncanny efficiency. “If you treat it like a giraffe, it responds the way a giraffe does,” instead of behaving like prey or prey’s hunters, and ignoring attempts by humans to herd them. That sounds a lot less like hive unification than it does a paradise where wildlife is freed from man’s harmful influence, but not assimilated to his will.

The shallowest reading is the one where the agent can affect animals by physiology (paralysis, etc.), but in general the planetary hivemind link is human. That preserves the show’s central tension between an overwhelmingly good humanity and a still-chaotic natural world.

If Zoos Emptied Out, Where Did Everything Go?

Real-world precedent points to a messy diaspora, not a Disney montage. The Association of Zoos and Aquariums, which represents more than 230 accredited zoos in the United States, points out that many exotics do not have the necessary foraging skills or exposure to diseases they would need to survive long outside human care. Some would scatter to urban green belts, golf courses, and agricultural peripheries; others would rapidly succumb to climate mismatch, malnutrition, or car strikes. Black-and-white photos of a giraffe consuming baboon dung and leaves are xeroxed onto posters titled “Suburban Animals,” which show that large herbivores can browse suburban trees; and apex predators follow prey trails, which explains all those maulings.

Domestic animals behave differently. It has been estimated by the World Health Organisation for a long time that approximately 75% of the world’s dog population are free‑ranging. In emergent disasters, dogs who become free-roaming quickly become scavengers and transition to nocturnal activity routines while expanding on their home range use. Consider after-hurricane study in the U.S. where animal organizations recorded an extensive dispersal of pets when human routines faltered. “All dogs off their chains” in Pluribus is consistent with that behavioral literature. Dogs do not need people to take them for a walk when food is abundant in abandoned pantries, as the stores are restocked; they go foraging on their own.

There would be an initial surge of birds and little mammals. Urban pigeons, crows, rats, and raccoons all prey on human leavings efficiently, and the Joined coordination of a city silenced makes for newly safer windows during which to grub or spear. Over the course of months, populations would settle on new waste streams and water sources; predators would scout out new territories. The result is not animal invisibility—it’s animals moving at times and in places our protagonists are not looking.

The Meat Paradox, Explained in the World of Pluribus

How can there be shelves of bacon if the Joined do no harm to life? Cold storage explains a lot. For weeks, even months, at a time, an inventory built over decades could be stored in these industrial freezers and refrigerated warehouses—or in the holds of a ship—so long as it was kept powered. Efficiently organized Joined crews could take stock of the reserves, establish a route, and distribute existing stocks throughout without decimating even one crew member. Fisheries would be forced to idle, just as feedlots and slaughterhouses connected to them must halt: frozen supply would flow down for a few weeks until it doesn’t. The Joined position is more like triage ethics—no new killing but practical use of what already exists for the non-Joined few.

What to Look For Next as Pluribus Reveals Its Rules

Three on-screen cues might clarify the show’s animal logic.

- Synchronized cross-species behavior—think flocks or herds all moving in linked unison—would support the idea that the hive is not just within us.

- A noticeable drop in roadkill or pest kills would confirm the work of the Joined to reengineer human–animal conflict zones.

- Straightforward lines about veterinary care, feed orders to sanctuaries, or tranquilizer-only wildlife control would determine how a kill-free ethic plays at scale.

For now Pluribus leverages the absence—and selective, feral presence—of its animals in service to unease. Scientists have estimated that there are around 8.7 million species on Earth, and yet this world feels emptied of anything nonhuman precisely because our point-of-view characters are cut off from the rhythms in which animals now traffic. Whether Gilligan is drawing back the curtain on some wider, collective consciousness or just keeping nature determinedly at bay outside the hive, he has turned a simple question into his show’s most unsettling mystery.