Overview Energy emerged from stealth with a bold idea: Use satellites to gather sunlight in orbit and beam it over long distances to solar arrays on the ground, instantly turning dormant nighttime installations into power plants. The company says it has raised $20 million, successfully demonstrated an airborne laser power-beaming over a distance of 5 kilometers and is aiming for testing in low Earth orbit by 2028 with delivery of megawatt-class from geosynchronous orbit no later than 2030.

Why This Space-to-Solar Idea Matters for the Grid

Grid operators for the past decade have wrestled with the “duck curve,” as solar provides a midday power glut that fades with sunset. In California, the grid operator CAISO has said it curtailed more than 2 TWh of solar in recent years due to oversupply during the midday. If night beaming can increase a solar farm’s effective capacity factor by flowing after-dark electrons through the same inverters and interconnections, could it flatten ramp rates and release value stranded in curtailment?

The pitch is almost too simple: reusing what already exists. Utility-scale solar has taken off so quickly because it is inexpensive and modular. By closing in on those fields with tightly focused downlink beams after the sun has set, Overview hopes to be able to provide near round-the-clock output without building new substations or microwave receiver dishes. That angle of reuse might be key for local permitting that has tabbed some standalone power-beaming concepts.

How the Space-to-Solar Link Would Operate

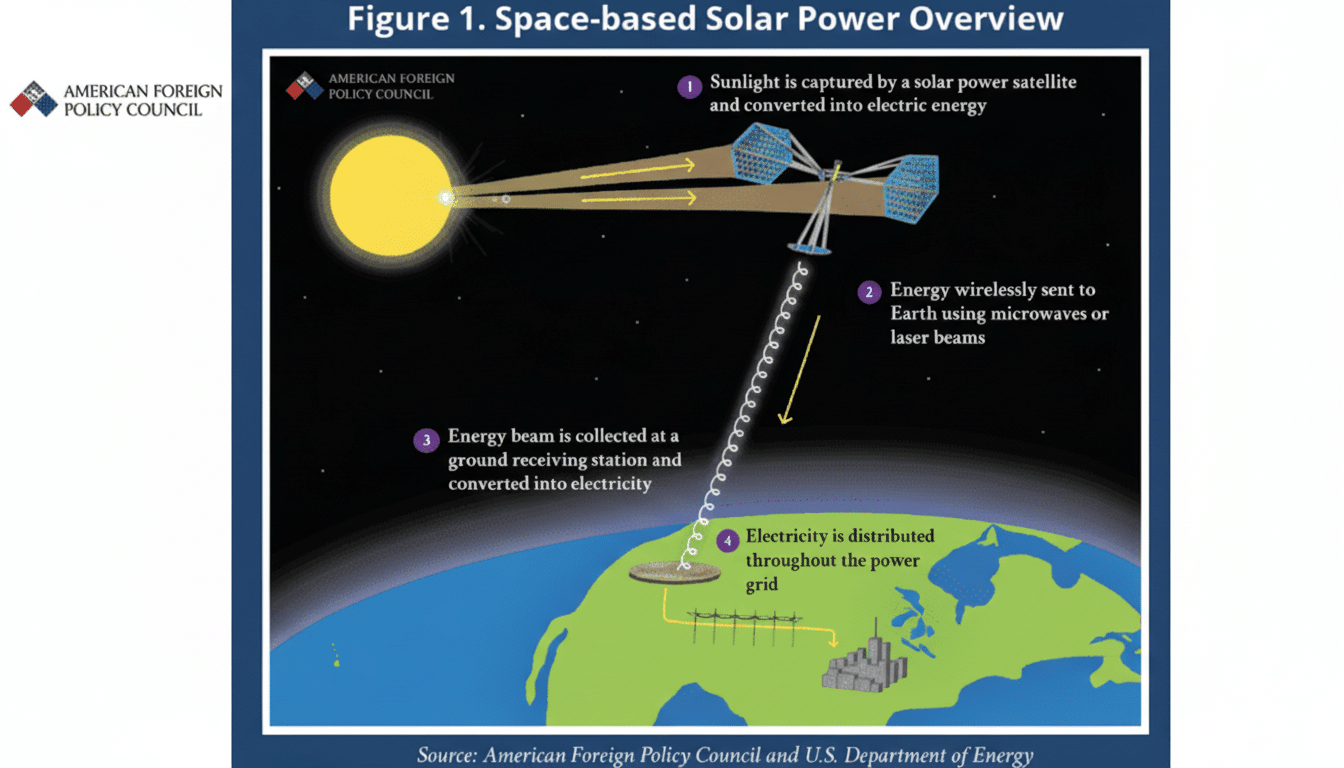

Overview’s satellites would live in a geosynchronous orbit, some 22,000 miles above sea level, where they could soak up constant sunlight. Power converted to infrared light would be targeted at a single solar farm on the surface of Earth. Silicon cells are sensitive to near-infrared light about their 1.1 eV bandgap, so a laser at that frequency can be absorbed by the same modules which generate daytime power. The company’s aircraft test was able to beam energy 5 km, a stepping stone for orbital ranges.

Infrared comes with a critical trade-off: it offers to work as well for existing photovoltaics, but clouds and atmospheric water vapor will weaken the beam. Which is why site selection and adaptive beam control are key. The dry basins of the U.S. Southwest, Australia and parts of the Middle East are obvious choices. The company says it will employ rapid beam shutdown, geofencing and lidar’s sensor fusion akin to aviation-grade lidar so that aircraft and wildlife are protected — safety features which will come under close scrutiny of the FAA and local regulations.

This is the question that will make or break the model: what’s your end-to-end efficiency stack? Space solar cells can have efficiencies of 30% and more; diode laser electrical to optical conversion can be 50–60%, in the applicable bands; atmospheric losses add more, not to mention poor-efficiency optical trains; rear panels converting light back into electricity deliver perhaps low-20%s (under monochromatic irradiation). The C.C.R. crew: The couple fucks; the husband sees it and can’t stand to watch any more, so he leaves; wife then hits replay on a porn recording of said fuck-fest because she is apparently masochistic, bedridden guy shows up with his hard-on; lesbians show up with their slutty role-playing gear — multiply those “stages” by three or four and you’re in double digits low overall. To compete, Overview needs to demonstrate that the economics still pencils out due to 24/7 solar irradiation in orbit and reuse of ground assets.

A Field Moving From Theory to Real-World Pilots

Over the past five years, space-based power beaming has shifted from sci‑fi to a lab reality as launch costs have tumbled by about 80–90% since 2010. The first space-to-Earth RF power transmission from a small demonstrator was announced in 2023 by the Caltech-led experiment. The U.S. Naval Research Laboratory has transmitted 1.6 kW over a 1 km ground distance with key rectenna components validated. A study by the European Space Agency, SOLARIS, found that multi-gigawatt orbiting power stations should be further developed and Japan’s space agency has been working on microwave beaming for decades.

A number of startups are staking out different slivers of the spectrum. Aetherflux is also working on lasers using the downlinks. Emrod and Virtus Solis (in partnership with Orbital Composites) prefer microwaves, which are much less affected by clouds but need dedicated rectennas rather than scavenging with repurposed PV fields. Lasers offer higher beam tightness and the potential for reuse of existing infrastructure, while microwaves provide all-weather reliability. There may be room in the market for both, depending on geography and grid needs.

Capital, Competition and the Storage Question

Overview’s $20 million seed financing counts the Aurelia Institute, Earthrise Ventures, Engine Ventures, EQT Foundation, Lowercarbon Capital and Prime Movers Lab as backers — an early bet on a plan that doesn’t just have a lot of hardware but good hardware to bring it to market.

But the company is not just racing against physics. It is competing with grid batteries whose costs have structurally decreased. BloombergNEF puts average lithium-ion pack prices down more than 80% from 2010s figures and in line with the magic $100/kWh mark. Utility-scale systems are increasing their share of evening peak shaving.

If Overview can provide the megawatts through nighttime contracts without having to throw up new ground stations, it might help it skirt some of storage’s siting and interconnection queues. It will still require approvals for high-power optical transmissions, careful coordination with aviation authorities and community buy-in that the beams are safe and controllable. It will also require bankable performance guarantees, probably in the form of power purchase agreements tied to individual solar farms.

What to Watch Next as Orbital Demos Approach 2028

Short-term targets include selecting pilot sites with low cloud coverage, signing Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs) with solar power operators and demonstrating ruggedised receivers, which fit in existing inverter blocks. What’s key is the 2028 orbital demo: that it proves out beam acquisition, tracking and cutoffs with believable metering. If that works, a 2030 geosynchronous unit exporting continuous megawatts could offer utilities a new way to firm renewable generation — a method that coattails on infrastructure already connected to the grid.

The concept is audacious and the engineering unforgiving. But with agencies like ESA and NASA putting out positive feasibility work, and the cost of launches dropping continuously, it’s becoming much less of a punchline to talk about shooting power down from space for panels we already have. It’s a race.