I woke up, checked my Oura app, and saw something I rarely do: Symptom Radar flashing major signs of strain. I felt fine, shrugged, and went to work. By nightfall the next day, I was shivering under a pile of blankets with a low-grade fever, wishing I had paid attention.

Most mornings, I skim my sleep and readiness scores out of habit. This time, there was a clear advisory even though no single metric looked dramatic. I assumed it was noise—maybe poor sleep quality or a stressful week. I hydrated diligently and carried on. Within 24 hours, a scratchy throat became heavy fatigue, then chills and a 100.7°F temperature. The ring had sounded the alarm before my body made it obvious.

Over the following days, my app lit up with the classic pattern of getting sick: elevated resting heart rate, suppressed heart rate variability, higher respiration rate, and a sustained temperature deviation. I spent most of the week resting, checking those lines each morning to see whether the trend was turning the corner.

What The Oura Ring Detected Before I Noticed It

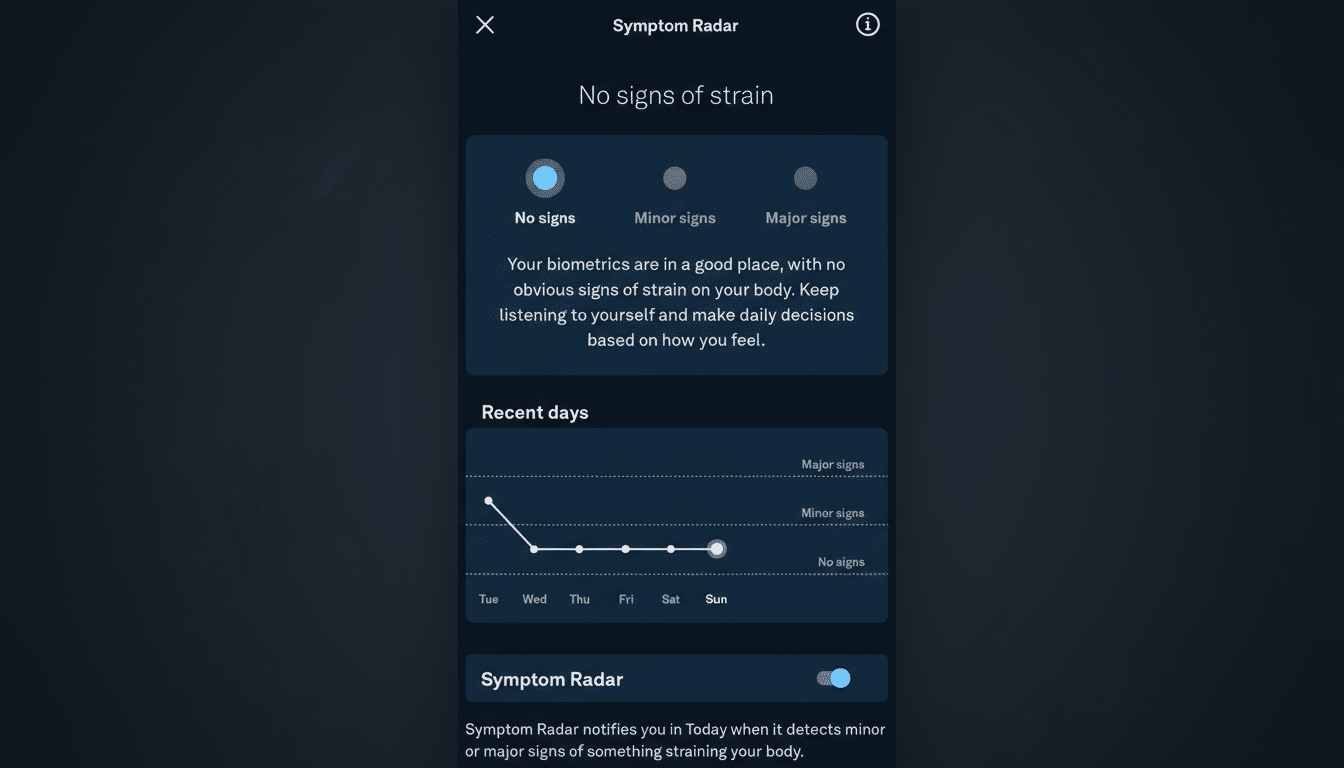

Oura’s Symptom Radar looks for a constellation of small departures from your baseline rather than a single red flag. When the system sees a cluster—slightly hotter skin temperature, a bump in resting heart rate, a dip in HRV, and faster overnight breathing—it infers strain. In my case, the numbers weren’t extreme at first. But together, they suggested my immune system was spinning up.

This multi-signal approach matters because illness rarely announces itself in one metric. A modest resting heart rate increase of 3–10 beats per minute, an HRV drop, and a respiratory rate climb of 1–3 breaths per minute are common in early infection. Skin temperature tends to rise a fraction of a degree before an actual fever. None of these alone proves you’re sick; together, they tell a story.

The Science Behind Early Illness Alerts From Wearables

Several research groups have shown that wearables can flag infection before symptoms emerge. Stanford Medicine has reported that continuous monitoring of heart rate, HRV, and skin temperature can detect respiratory illnesses one to three days before people feel unwell. During the pandemic, UCSF’s TemPredict project with Oura found that ring-derived temperature deviations often anticipated fever onset, supporting early-warning models.

Scripps Research’s DETECT study similarly demonstrated that changes in resting heart rate and sleep patterns from consumer wearables can help track influenza-like illness at both individual and community levels. Public health agencies such as the CDC have noted that these aggregated signals can mirror real-world waves of cold and flu activity—even though they are not diagnostic tools.

Real-world anecdotes echo the data. Health-care workers have credited rings and watches with flagging abnormal patterns that prompted checkups, sometimes leading to serious diagnoses caught earlier than they might have been. Others have described unplanned pregnancy detection when temperature and heart rate trends shifted unexpectedly. The common thread: continuous data surfaces subtle physiologic shifts that sporadic measurements miss.

How To Read The Signal Without Overreacting

Context is everything. Alcohol, late-night workouts, red-eye flights, high stress, and poor sleep can all mimic “strain.” Before you panic, scan the previous 48 hours for obvious confounders. If none apply—and you see two or more metrics moving in the wrong direction—treat the alert as a nudge to ease up, prioritize sleep, and watch for symptoms.

Wearables are sensitive, which means they will occasionally be wrong or early. They aren’t medical devices and can’t diagnose illness. But when a pattern persists across multiple nights, it’s rational to scale back intensity, hydrate, and consider a rapid test or a call to a clinician if symptoms appear. Early rest can shorten recovery; early denial often does the opposite.

Lessons From Ignoring A Good Early Warning Signal

I used to glance past subtle alerts. This week changed that. The ring didn’t prevent my cold, but it gave me a 24–48-hour head start to avoid hard training, reduce exposure to others, and plan a lighter workload. Once I was sick, the data helped me track a turnaround: resting heart rate drifted down, HRV rebounded, and respiration rate settled—signs that the fever had broken before I felt fully normal.

My takeaway is simple: don’t treat an early-warning banner as a diagnosis, but don’t treat it as noise either. Continuous biometrics are good at noticing when your body is fighting something long before your brain admits it. The cost of heeding the signal is small—an easier day, extra sleep. The cost of ignoring it can be a week lost to bed and regret.