NASA’s initial asteroid sample return mission returned more than hoped for, as a trio of discoveries broadens ice-filled crater collections in the early solar system. Studying pristine grains from asteroid Bennu, analysts detected biologically important sugars, an enigmatic gum-like organic compound referred to informally as “space plastic,” and a surprising abundance of stardust that formed more than five billion years ago in distant supernovas.

The new findings, published in Nature Astronomy and Nature Geoscience, are from the samples collected by OSIRIS-REx nestled inside a carefully sealed jar of crushed rock and dust. Together, they imply that carbon-rich asteroids such as Bennu carried a fuller complement of prebiotic compounds to young worlds than scientists had direct evidence for until now.

- Why Bennu Matters for Understanding Early Solar System Chemistry

- Sugars Point to an RNA First Step in Life’s Early Origins

- A Peculiar Gum-Like Polymer Found in Bennu’s Organic Mix

- Stardust in Abundance Across Bennu’s Ancient Regolith

- Implications for Life’s Origins From Bennu’s Rich Chemistry

- What Comes Next in the OSIRIS-REx and Bennu Research Journey

Why Bennu Matters for Understanding Early Solar System Chemistry

OSIRIS-REx launched in 2016 and extracted its sample from Bennu in 2020, traveling on a multiyear, approximately 4-billion-mile round trip before leaving the capsule to drop into the Utah desert in 2023. It is the first U.S. mission to retrieve material from an asteroid and return it to Earth-based laboratories, offering a half-cup of fine regolith as welcome cargo.

Bennu is a dark, carbon-rich body that scientists believe may have formed in the outer asteroid belt before moving inward. It hasn’t gone through much geological processing, so it serves as a time capsule for compounds that were around when the solar system was young — an attractive place to study where life’s raw ingredients came from and how they arrived here.

Sugars Point to an RNA First Step in Life’s Early Origins

In the journal Science Advances, a team led by Yoshihiro Furukawa of Tohoku University identified six types of sugar among Bennu’s dust, including ribose and glucose.

Ribose is at the core of RNA, which can store information as well as catalyze reactions; glucose is a basic currency of cellular energy. And importantly, it’s the first time glucose has been found in hyper-clean asteroid material, adding more weight to the argument that complex organics formed far out in space, not just on Earth.

Equally striking is what’s not there: deoxyribose, the sugar that makes up DNA’s backbone. That void buttresses the so-called RNA world theory that contends that RNA predates DNA and proteins in the simplest steps toward life. The prevalence of certain life’s building blocks throughout the solar system means that it is more likely life’s chemistry established itself whenever and wherever conditions were right, according to NASA astrobiologist Danny Glavin, a co-leader for organic analyses on the sample.

The discovery follows previous findings in meteorites and samples from Japan’s Hayabusa2 mission to the asteroid Ryugu, where amino acids and nucleobases were found. Together, researchers are now observing the full suite of prebiotic building blocks — amino acids, bases, and sugars — in space rocks that made it to planetary surfaces.

A Peculiar Gum-Like Polymer Found in Bennu’s Organic Mix

In another study, researchers led by NASA’s Scott Sandford reported that they had found a complex organic material with what is essentially the composition of polyurethane-like chemistry. This is not plastic manufactured by people; rather, it’s a naturally occurring polymer that seems to have assembled in radiation-driven reactions on icy dust grains and then subsequently dehydrated on the parent body of Bennu. When it was young, it is believed to have been sticky and gum-like, and could have served as a scaffold that focused and organized smaller organic molecules.

The find widens the inventory of extraterrestrial organics for studying the impact that compounds like tars and oils from carbonaceous meteorites may have had at an early stage on life. It hints at the possibility that nature may have put polymeric structures together in outer space — perhaps precursors to life that got their start long before planets cooled down and stabilized.

Stardust in Abundance Across Bennu’s Ancient Regolith

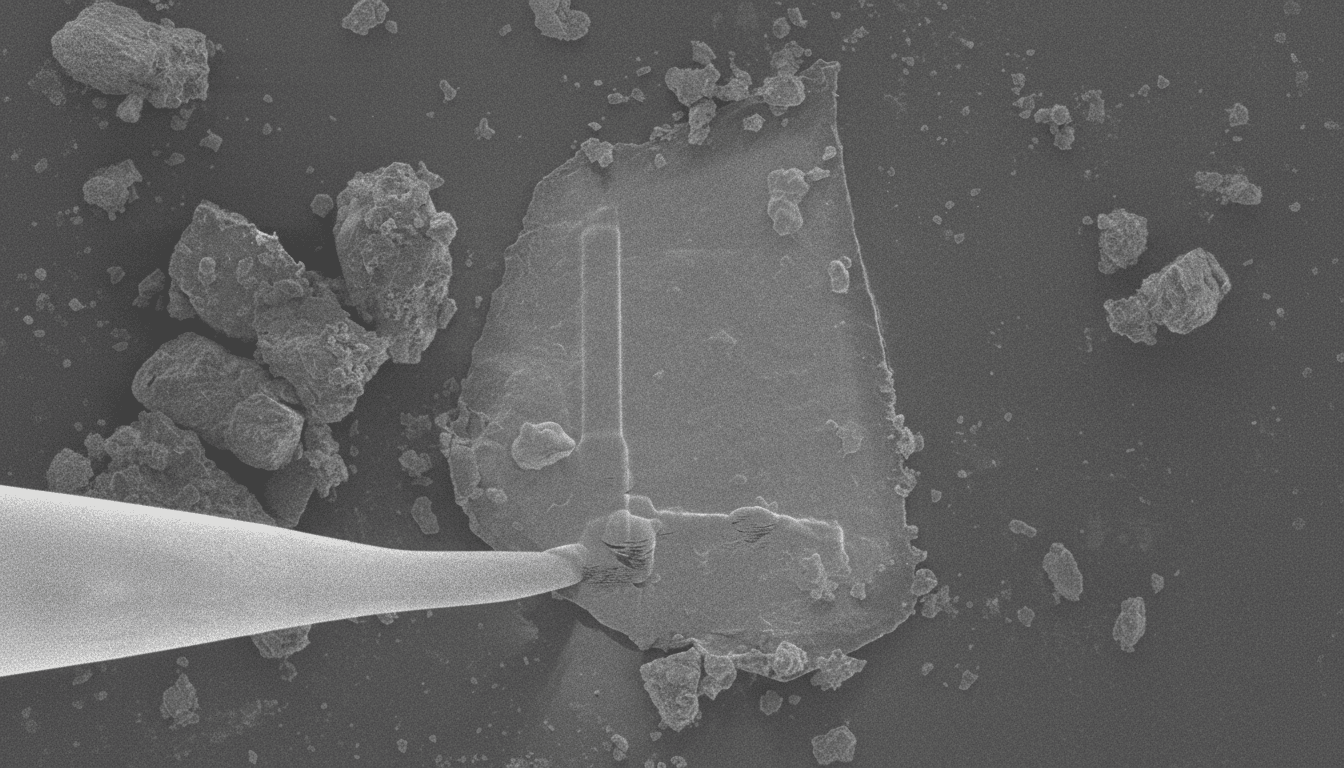

A third study, led by NASA planetary scientist Ann Nguyen, is about “presolar grains” — microscopic minerals that condensed around dying stars, and somehow survived the birth of our solar system. Bennu’s sample has an exceptionally high abundance of such grains, about 30 times more than ever measured in the previous extraterrestrial material studied in labs.

That enrichment means Bennu’s parent body formed in an area filled with debris from explosive deaths of massive stars. While the evidence suggested liquid water changed some of the asteroid’s rock, pockets that remained relatively unaltered revealed delicate presolar grains and organics. Those sheltered crannies are a rare window into the pristine stardust and channels by which exotic atoms and molecules were mixed into the earliest building blocks of planets.

Implications for Life’s Origins From Bennu’s Rich Chemistry

The findings together reinforce an enduring notion: that early Earth was laden with biologically relevant molecules delivered by carbon-rich asteroids. Repeated impacts of sugars, amino acids and nucleobases might have blended in wet-dry cycles, hydrothermal systems or tidal flats to steer chemistry toward self-replication and metabolism. The Bennu findings strengthen the case it was feasible because key ingredients were plentiful and readily shunted around.

They also help to account for why meteorites like Murchison and the Tagish Lake falls are enriched in organics, and serve as a so far uncontaminated baseline that meteorites simply can’t beat. That rigor — plus clean-room handling at NASA’s Johnson Space Center and extensive blank controls — renders Bennu an anchor point for testing origin-of-life scenarios.

What Comes Next in the OSIRIS-REx and Bennu Research Journey

Only a small sampling of the contents has been analyzed so far. Now teams are studying isotopic fingerprints to look for reaction pathways that could account for the formation of sugars and polymers, and comparing Bennu’s chemistry with Ryugu’s in an effort to chart diversity among carbonaceous asteroids. All the while, a spacecraft known as OSIRIS-REx (it has since been renamed) is headed toward the asteroid Apophis, offering a unique opportunity to see how solar system bodies change over time after having a close encounter with Earth.

For astrobiology, the news is increasingly the same: The cosmos is good at both making and moving life’s starting kit. Now, armed with Bennu’s chemistry, researchers have a better roadmap for how those incipient systems of life might have pieced themselves together — and where else we should be looking now on the hunt to hear echoes of that process.