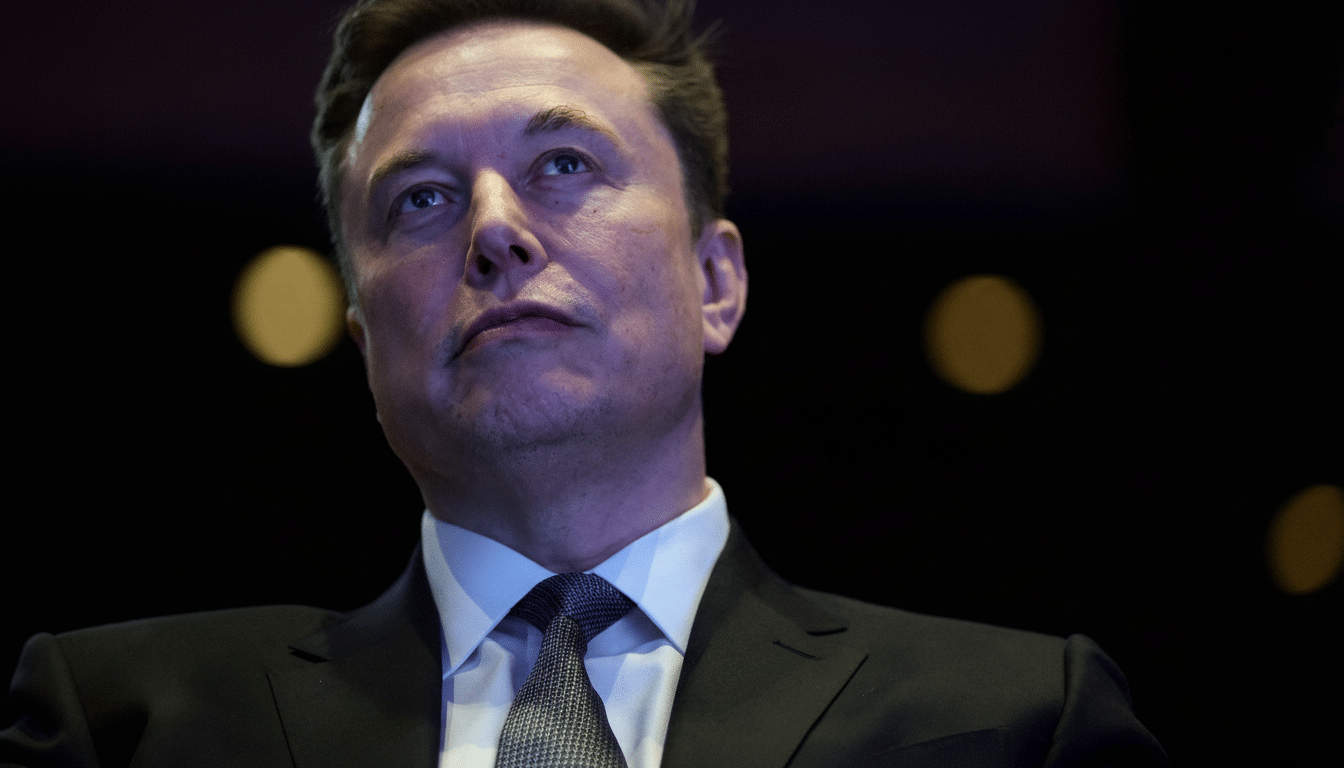

A lawsuit by Elon Musk against OpenAI that he had boasted would detonate in a “nuclear” explosion on Wednesday has been resolved without damaging both the lab and Musk, who did not back up his swagger with any evidence at trial. A federal judge has found that there is enough evidence for jurors to consider whether leaders at OpenAI led Musk to believe the organization would keep its mission to focus on beneficial AI — which benefited everyone — and whether those assurances still mattered once power and money were in play.

What the judge signaled about evidence and promises

U.S. District Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers said the record contains “supportive evidence” that OpenAI’s leadership has made parallel commitments about keeping its original nonprofit structure. That doesn’t make the case, but it crosses the threshold for a jury to determine whose story stands up under cross‑examination. Now the central questions are whether there were any concrete promises, whether Musk could be considered to have reasonably banked on them, and if OpenAI’s later restructuring and commercial move went back on some binding pact.

Juries, by and large, focus on contemporaneous documents and credibility. Emails, board materials, fundraising decks, and governance memos could be damning. If jurors encounter specific language that reads like a pledge, Musk’s claims carry more weight; if they encounter standard-issue nonprofit boilerplate about intent and values, OpenAI has the stronger defense.

The core claims and defenses each side will present

Musk claims he put in about $38 million, provided reputational capital, and advised the lab on the theory that OpenAI would stay mission-first and noncommercial.

He says subsequent decisions — to bring frontier models to market, woo large corporate partners, and raise the profit pressure he warns against — violate those pledges and led to “ill‑gotten gains” for which he seeks damages.

OpenAI argues that it designed a capped‑profit model to scale gradually and support huge compute, research, and safety expenses while still maintaining a mission lock. (It later spun off of the for‑profit arm into a Public Benefit Corporation, with the original nonprofit holding 26 percent equity, an architecture intended to formalize public‑interest duties.) Leadership has argued that these measures are in line with, not against, the mission and that revenue maximization was never a means unto itself. The company’s well‑publicized collaboration with Microsoft is often invoked as required capital and infrastructure to remain competitive at the frontier.

Context matters: Musk co‑founded OpenAI, then left the board and started his own AI effort, xAI. He also put forth an unsolicited $97.4 billion takeover bid that OpenAI rebuffed, highlighting a strategic divide over governance and control. You can expect the defense to argue that his interpretations are self-interested; you can expect the plaintiff to argue that competition doesn’t have the power to wipe out a broken promise.

Why a trial by jury matters in this nonprofit dispute

Most of these nonprofit governance disputes never make it to a civil jury; they’re usually resolved by judges interpreting bylaws, charitable trust doctrines, or attorney general oversight. Bringing this case before jurors ups the ante. Donors and early backers generally don’t have strong standing to enforce broad mission statements unless they are backed up by contracts or evidence of reasonable reliance — that’s where promissory estoppel and implied‑contract theories can factor in, according to commentaries provided to The Times by the American Bar Association as well as nonprofit law experts.

From a pragmatic standpoint, the most likely solution is monetary damages, not unwinding OpenAI’s formation. Injunctive relief to enforce governance reversals is unusual, particularly following a concluded restructuring involving third-party stakeholders. Still, a verdict against Musk could deter bold restructurings throughout the industry, leading to more explicit founder agreements and clearer donor contracts. A victory for the defense might lend legitimacy to mission‑linked profit models if governance checks are adequately documented.

Potential impacts on the AI industry and governance

The trial comes at a time when it costs ever more to train and deploy cutting-edge models, with compute workloads, data center build-outs, and specialized chips demanding deep, sustained investment. Research outfits like Stanford HAI and Georgetown’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology have documented this capital intensity, as well as the increasing dependence on strategic partners. That dependence collides with purist nonprofit values, and this case will test whether hybrid models can truly harmonize public benefit with the scale the field needs.

Key signals to watch:

- discovery disclosures on early governance promises

- board deliberation around the capped‑profit and PBC structures

- how mission‑priority provisions play out in practice

- conversations among jurors on whether a 26% nonprofit stake is meaningful guardrails or window dressing

Wherever it falls, the jury’s decision will shape more than one company’s story. It may help establish what weight legally binding mission pledges should have in an era in which AI development is simultaneously a global public good and a capital‑intensive dash for advantage.