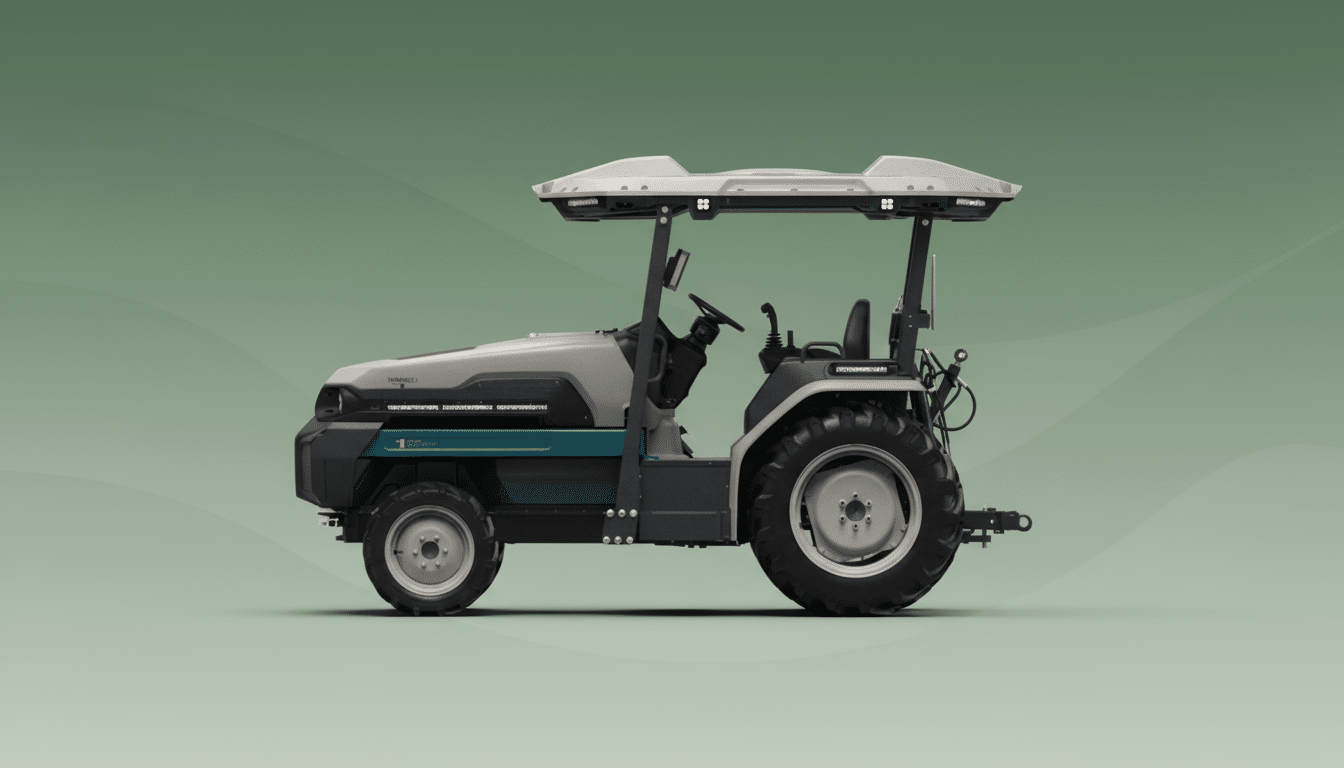

Monarch Tractor is the target of a federal lawsuit claiming it overstated how self-driving its electric farm tractors really are, dealing another setback to one of agtech’s more visible wagers on autonomy. The Idaho-based dealer Burks Tractor says the machines it had agreed to purchase were “not able to work without a driver, as represented” and is suing for breach of contract and breach of express and implied warranties. Monarch has denied the allegations in court papers.

Dealership Alleges Broken Promises in Tractor Deal

Through those brief conversations (“I thought I was talking to somebody who had a nickel”), Burks Tractor allegedly agreed to buy 10 Monarch units and signed on to be one of the startup’s first dealers, according to the complaint. The dealership says it paid $773,088 for the tractors and financed their purchase, so interest costs are still mounting. Spare parts were purchased as separate items, and deliveries were done in two shipments.

According to Burks, the issues were immediate: The tractors did not work as promised or run on their own. The dealer says Monarch’s sales team tried to diagnose the problem but ultimately admitted in communications that the autonomy they promised was not functional, including being unable to work indoors. Burks says that the equipment went for months without proper support, and they received no acknowledgment to their many attempts at repairing, replacing or returning the equipment.

The case originated in state court in Idaho and was transferred to federal court. Monarch’s chief executive and its counsel did not make any public statement, but court documents indicate that the company is contesting the allegations and plans to fight them.

Autonomy Claims Under Scrutiny in Farming Equipment

At the heart of the dispute is what “driver optional” looks like in practice on a conventional field. That level of autonomy in agriculture usually requires a stack of technologies — GNSS with RTK corrections for centimeter-level location, multi-sensor perception (LiDAR, cameras, radar), and path planning tuned to particular crops and terrain. Even well-established systems can be limited by tree canopy, signal multipath around buildings, dust contamination and changing lighting. Beyond this, it is particularly challenging to operate indoors where satellite positioning does not work: vendors are forced into use of SLAM-based solutions and pre-mapped environments which can be difficult to rollout and maintain.

Dealers and growers are not strangers to precision guidance systems and supervised automation, yet hands-off operation in a wide range of fields across multiple terrain types is demanding. The question, perhaps, is whether Monarch described its tractors as autonomous “without limitation by location or time,” it did so in the language of those allegations and what disclaimers accompanied the representations — as well as whether the dealer unreasonably relied on marketing materials or demo videos to reach an agreement.

Strains at the Startup Reflect Changing Strategy

Monarch has spent years positioning itself as a technology pioneer for electric, software-defined tractors designed for vineyards and dairy operations. The company has also been through a series of layoffs and strategic changes. And Monarch, the factory in Ohio where contract manufacturer Foxconn had assembled tractors, is now being converted into an AI data center — a sign of broader disruptions and turbulence around supply and production across the sector. More lately, Monarch has focused on software and licensing, hinting at a shift to a lighter-asset model as hardware timelines elongated.

Those pressures are reflective of what a lot of startups developing autonomous farm equipment encounter: a capital-intensive hardware roadmap, long validation periods with growers and heavy support demands once machines leave the pilot phase. Dealers in turn have expectations around consistent uptime, clear service paths and contracts that replicate real-world performance — not staged demo results.

Industry Context And Technical Challenges

Autonomy is marching forward in agriculture, although today most commercial deployments are geofenced and monitored.

John Deere has demonstrated autonomous features on high-horsepower tractors and incorporated technologies from acquisitions such as Bear Flag Robotics and Blue River Technology. CNH Industrial has also advanced supervised autonomy through Raven. There are also European players, like Naïo Technologies and AgXeed that have concentrated on specialty robots for vineyards and arable fields. These systems often do work in narrow applications, settings with strict safety protocols and remote supervision.

The market forces are undeniable. For its part, demand for automation remains high as chronic labor shortages were reported among producers and rising wages in USDA surveys. Analyst houses monitoring agricultural robotics see strong double-digit growth throughout the decade as electrification, computer vision, and connectivity all improve. But there remains a chasm between a slick demo and a reliable, dealer-supported product. Even programs with reasonable funding are still struggling in the areas of indoor autonomy and mixed terrain, as well as complex crop canopies.

What Comes Next for the Lawsuit and Autonomy Claims

Legally, the battle will be one of contract terms, express and implied warranties and remedies under the Uniform Commercial Code — any or all which might include rescission, repair and replacement, or damages. In practical terms, it’s a test of confidence for Monarch dealer strategy and buyers considering early autonomy deployment.

You can anticipate a sharper eye on performance guarantees, acceptance testing and service-level agreements on all ag autonomy deals. For startups, that’ll entail getting a handle on your operating envelopes with more precision — what “outdoor vs. indoor” will look like, line-of-sight requirements, base-station placements — and aligning marketing language with the reality of sensor fusion and perception limits. For manufacturers and growers, it highlights the importance of a staged rollout, clear KPIs and trial periods associated with payment milestones.

Whether this case settles or goes to judgment, it makes a larger point about autonomous agriculture: the reliability that stands up under uncontrolled conditions that fluctuate by season is an output — it’s not a feature. It is narrowing of that gap where the winners in the category will come from.