Meta is delaying the launch of its next-generation mixed reality glasses to, at the earliest, the first half of 2027, Business Insider reported, changing a product that was originally aiming for a late-2026 release. The website cited internal memos in which the device goes by the codename Phoenix and is pitched as a move to focus on quality and long-term viability over speed.

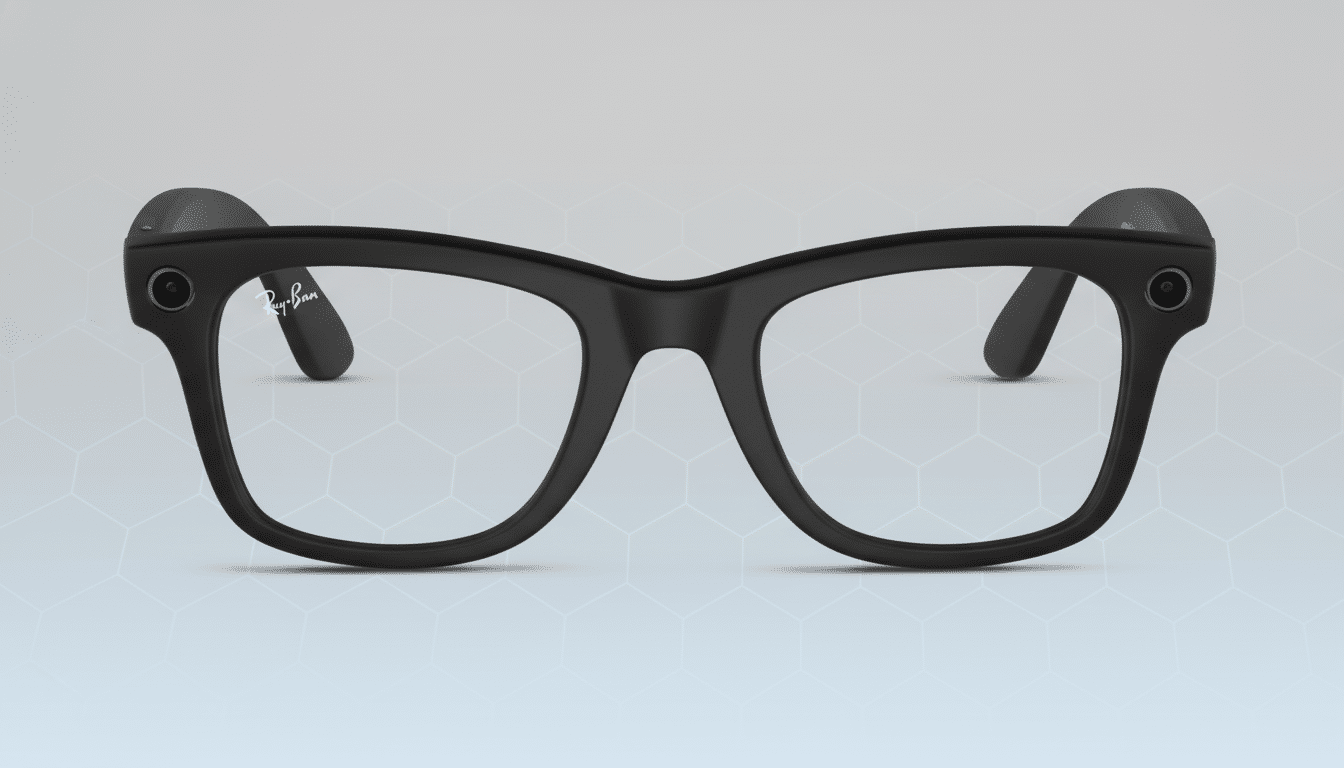

The delay highlights how challenging it still is to ship consumer-ready, high-end mixed reality hardware at scale. It also marks an about-face for a company that has invested billions into immersive tech while managing demand for practical, everyday wearables like its Ray-Ban smart glasses.

What Changed and Why It Matters for Meta’s Timeline

Meta execs told teams about the schedule delay following conference-room meetings where CEO Mark Zuckerberg emphasized prioritizing sustainable business growth and high-quality experiences, according to Business Insider. Managers running the effort, including Gabriel Aul and Ryan Cairns, told employees that the additional time would provide teams with ‘breathing room’ to figure out all of the details, the communication allegedly added.

The timeline matters because it puts Meta’s most ambitious glasses well into multiple product cycles ahead of rivals. Apple’s Vision Pro set the mold for today’s high-end mixed reality, and Meta’s own Quest line is chasing mass volume at lower prices. Locking Phoenix out of the market until 2027 implies Meta knows it needs major improvements in comfort, optics, and battery life before it dares take on the premium tier with glasses you’d actually wear for hours, not minutes.

Inside Project Phoenix and Its Evolving Design

Phoenix is a mixed reality glasses platform with a more compact, headset-like design than actual eyewear. The post mentions that it comes with an external puck-shaped power source — similar to the battery pack Vision Pro comes with — to reduce weight (on your head, at least) and heat. That option suggests the company is talking more about power-hungry displays and compute, perhaps with advanced microdisplays and a solid sensor stack.

Getting that architecture correct is anything but trivial. High-brightness micro-OLED panels, the precision in alignment of waveguides, and low-latency passthrough are extremely demanding with regard to tolerances and thermal design. The trade-offs that come with this are felt everywhere, from comfort to field of view to price — every gram and watt matter. The 2027 target provides Meta with time to iterate on optics, weight distribution, and cost before scaling up production.

Budget Squeeze and Market Reality for AR/VR Growth

The tactical pause follows financial pressure. Meta, led by Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg, is cutting metaverse-related spend by as much as 30%, Bloomberg reported this week, in a significant scaling back after years of heavy investment. Meta revealed in 2023 that Reality Labs was accruing close to $16 billion in operating losses despite building up a leading share of consumer VR with the Quest line.

Market dynamics add pressure. Market research firms including IDC and Counterpoint have pegged global annual shipments of AR/VR headsets in the single-digit millions, with Meta enjoying a commanding lead by unit share. It’s a significant scale for developers to take seriously, but still smaller than smartphones and harder to justify investing in bleeding-edge, expensive hardware that doesn’t have an obvious path toward volume.

Competition and Supply Constraints Shaping the Roadmap

Apple’s Vision Pro, a prototype that set the bar for mixed reality fidelity, also underscored bottlenecks in the category: expensive microdisplays with poor yield and ergonomic trade-offs of tethered batteries.

And there has been a series of supply chain reports suggesting limited availability for high-quality micro-OLED panels and complex lens assemblies, components that directly affect weight, brightness, and price.

For Meta, taking the long view may be pragmatic. Costs for components are expected to decrease as manufacturing gets off the ground, and next-wave silicon can often offer better performance per watt. By 2027, the company might be able to bring Phoenix into an ecosystem of parts with higher yields, better optics, and a clearer cost envelope — necessary if it wants to land on a price that opens up the addressable market beyond enthusiasts.

How It Fits Meta’s Wearables Strategy and Product Mix

Meta already straddles dual tracks — mainstream VR headsets for immersive gaming and productivity, and lightweight Ray-Ban smart glasses for capture, communication, and hands-free AI support. The latter indicates that form factors that fade into the background are a major contributor to daily use, with or without complete mixed reality visuals. Phoenix seems to bridge the divide — significantly more immersive than sunglasses, but pushing toward all-day wearability.

Pushing back Phoenix might also allow Meta to intensify work on software and services. The company is investing in multimodal AI and spatial computing frameworks, while a more polished OS, hand tracking, and developer tools make for a more perceptible increase at launch. The optics are as important as a strong content pipeline.

The Outlook for 2027 and What to Expect Next

If that 2027 target holds, Meta will spend the next two or so years tweaking hardware, securing supply, and reining in costs for a market that is growing but still in its infancy. It’s a broader industry lesson as well: mixed reality is going to be, in large part, about whoever can wait and who puts in the polish rather than who gets there first.

The message is unequivocal for developers and partners. Look for Quest and Ray-Ban platforms to continue receiving support in the short term, with Phoenix sitting as a more ambitious next step once the ‘drunk girl at a party’ that is technology meets similarly drunken app economics. If Meta is able to do that — make a lighter, brighter, and longer-lasting device available at consumer-friendly prices — the wait will instead be remembered not so much as a delay, but rather the table stakes of what’s next for spatial computing.