The head of Memento Labs admitted that one of the firm’s government customers was caught using its Windows spyware, in a rare admission from an industry known for covert work. The confirmation came after new research by Kaspersky linked the Milan-based vendor to a previously unknown surveillance tool called Dante and documented active targeting of people within Russia and Belarus.

Dante spyware tied to Memento Labs operations

Dante was used by an operator they monitor called ForumTroll, which tricked Russian-speaking targets into clicking on invitations to a highly respected Russian politics and economics conference, the Primakov Readings. The campaign targeted media outfits, universities and government organisations across the country, they said, employing phishing links as vehicles.

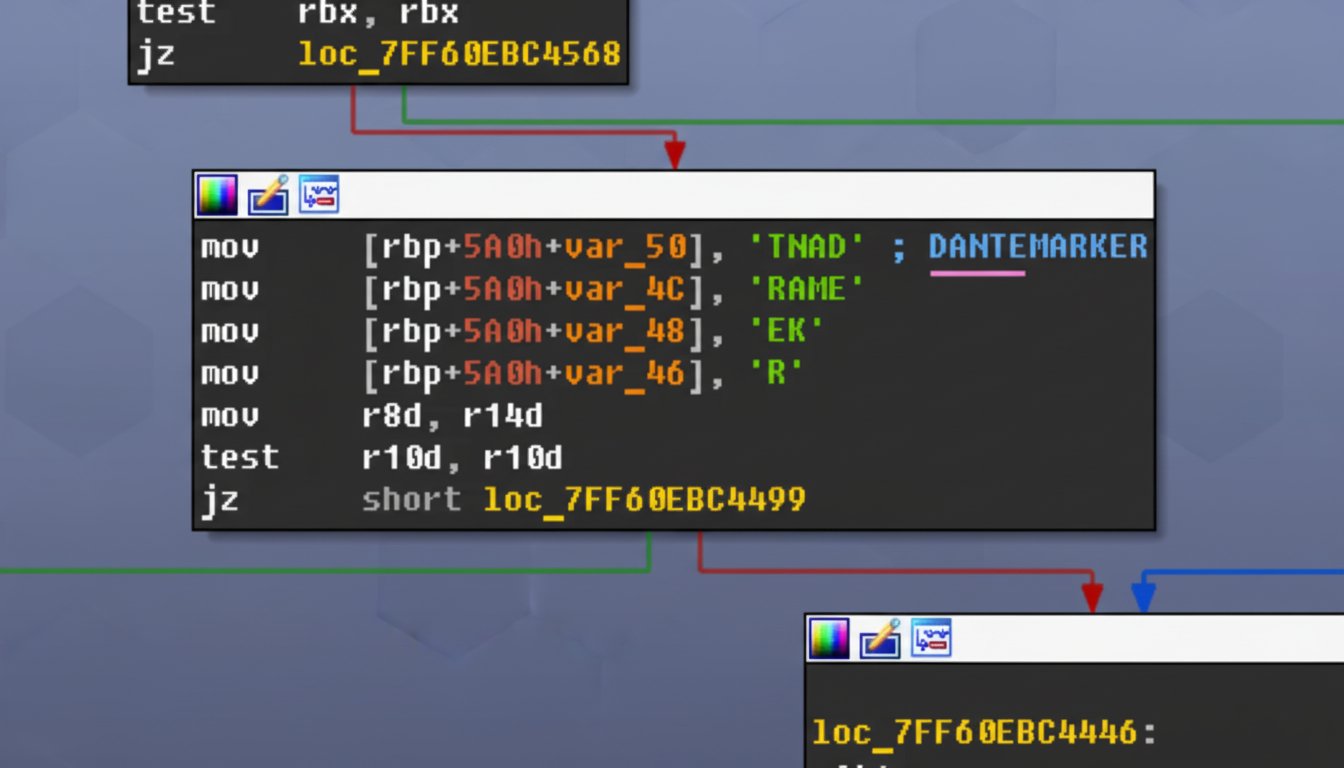

The report also included technical evidence to suggest Memento Labs is behind the spyware, such as a string left in the code that says “DANTEMARKER,” which matches the name of the spyware family that had previously been publicly hinted at.

Analysts said there were continuities with behavior from earlier tools linked to Hacking Team — an Italian maker of spyware now defunct, but whose assets and engineering know-how were taken over, then rebranded Memento Labs in 2019.

At the same time, Kaspersky noted that the most recent wave of intrusions used a Chrome zero‑day as part of their watering hole attacks to assist in victim compromise. The exploit used against Memento, the chief executive said, was not their own, and the company often buys browser and mobile exploits developed by others rather than builds them all themselves.

Outdated build prompts CEO to order spyware phase‑out

After the research was published, the CEO—whom Motherboard refers to as Lezzi—replied with a statement that one of the company’s government clients had used an older Windows implant that Memento plans to phase out by year’s end.

“I thought [the government customer] didn’t even use it anymore,” he said, and the company had already informed customers that Dante infections were being detected as early as 2024.

Lezzi said it was unclear which client was at risk, but that Memento would remind everyone to immediately cease use of its Windows spyware. The company had declined to tell his team how their tools work, he said, and a few months later sent them another Twitch clip saying that the iPhone had not been compromised by a specific technique the ZeroCleare researchers discovered to bypass Apple’s security protections. (A spokesman for Vupen acknowledged making that claim in an email but said it was mistaken.) The company now works on mobile surveillance products, he added, and keeps only a small internal program focused on zero‑day research while buying others from the market.

From Hacking Team’s legacy to Memento Labs today

Memento’s ancestry goes back to Hacking Team, which was one of the giants in Europe’s commercial spyware sector before a crippling leak of its internal data at the hands of the hacker known as Phineas Fisher. That breach revealed contracts and client operations, revealing usage among customers in Ethiopia, Morocco and the United Arab Emirates against journalists, dissidents and political opponents. Later reporting also linked the company’s sales to countries with poor human rights records including Bangladesh, Saudi Arabia and Sudan.

Having paid only a nominal sum for Hacking Team’s assets, Memento Labs pitched a fresh start and new controls. Kaspersky’s findings indicate, however, that the company apparently kept working on fine-tuning the aging Windows platform until about 2022 when it was supplanted by Dante. The handoff is visible in design patterns and code markers, such that the throughline from the latter development to Memento’s implant families was strengthened.

Less running room for mercenary spyware vendors

The case points to a reeling environment for “mercenary” spyware vendors. Detection is gaining ground as endpoint security vendors and independent testing labs focus on commercial surveillance tooling in addition to nation‑state malware. The proliferation continues, says Citizen Lab, a research group at the University of Toronto that has monitored abuses for more than a decade, despite headline‑grabbing exposures, in part because new customers and intermediaries continue to surface even as some tools are burned.

Pressure from governments is also growing. Export‑control regimes have also increased their scrutiny of intrusion software, and some countries have banned procurement or restricted trade with vendors implicated in abuses. That has led companies to promote their compliance programs and customer vetting processes — but this episode is a reminder that even cursory protections don’t work if an operator takes an old or shabby build into the wild.

Key technical takeaways from the Dante campaign

Key points from the Dante campaign for defenders include:

- Phishing remains the primary initial access vector.

- Browser zero‑days are still used alongside second‑stage payloads.

- Unique code markers, such as stray strings, aid attribution.

Kaspersky’s monitoring of infections for several months indicates the operator emphasized stealth and longevity ahead of quick mass compromise, in line with other targeted surveillance operations.

For Memento Labs, it will need to focus in the near term on containment: retiring its Windows toolset, herding any customers that are still using those tools away from them, and trying to prevent cross‑contamination between legacy code and more recent mobile offerings. Whether the company can persuade regulators and watchers that it has cast off its worst inheritance will depend on a level of transparency to which the sector has been historically allergic, and whether questions continue to be asked about how much more misuse is being uncovered in real time, often by independent researchers.