An Indiana bankruptcy lawyer named Mark Zuckerberg has sued Mark Zuckerberg, the chief executive of Meta, claiming that Meta’s automated enforcement repeatedly treated his legitimate Facebook business presence as an impersonation attempt. This, all of it, is all possibly funny to you, not because it’s obviously a punchline, but because on a granular level you disagree about the authenticity of the platforms and of their moderation, and on the advertising spend on the platforms in support of the surrounding issues of identity.

A name collision turns into a legal battle

The lawyer, a 21-year practitioner in Indiana, said his professional Facebook page has been removed several times over the past eight years because the systems had mistaken him as being an impostor of the famous tech executive.

He isn’t. He just has the same name, and has for decades.

Local coverage from Indianapolis station 13WTHR was the first to highlight the filing and the years-long paper trail of appeals. In a statement to the station, Meta said it knows that many people have the same name and is looking into the issue.

The complaint: ads paid for, pages taken down

The attorney’s commercial Facebook page “is at the heart of his means of client intake,” the suit says. He said it has been disabled three times over eight years, disrupting communications with potential clients and eroding the effectiveness of paid campaigns to promote his services.

He lists more than $11,000 in advertising buys on Meta’s platforms, and claims those expenses did not stop when his page was mistakenly deactivated.

The filing includes correspondence going back to 2017 that shows repeated efforts to have the page restored and to make sure the same misstep did not happen again.

Off-the-charts confusion around his name — missed calls, wrong number fan mail, even nasty messages for the CEO — is chronicled on a personal website kept by the attorney to vent over the misidentification. But the actual harm occurs when those mix-ups spill over into his business via automated enforcement, the lawsuit argues.

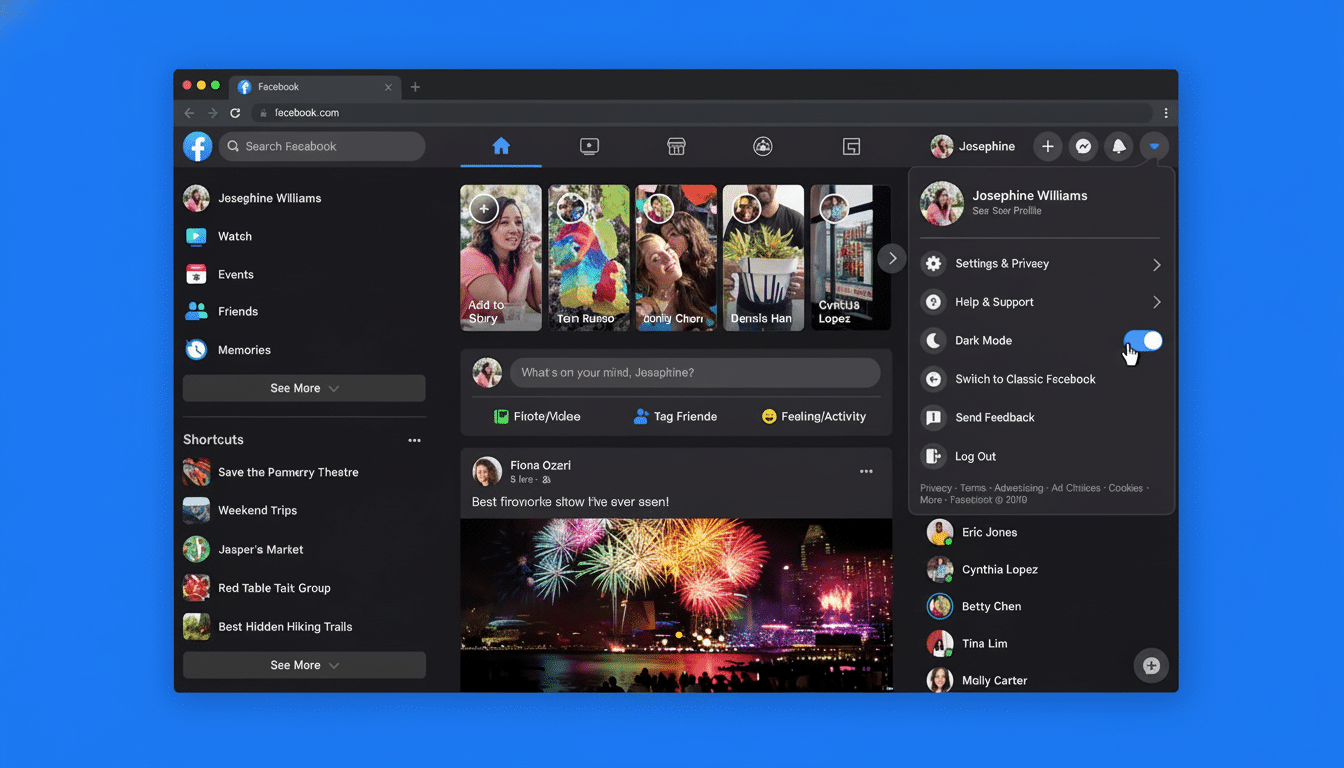

Meta’s scale moderation and false positives

Impersonation is a serious threat on these networks, and Meta spends heavily to prevent it. The company’s regular Community Standards Enforcement reports highlight in the billions the number of fraudulent accounts that are taken down each year — an indication both of the size of the threat and the number of automatic decisions made by the detection systems.

But those systems can misfire. The Oversight Board, Meta’s independent content review body, has told the company on several occasions that it should deliver better, clearer notices, stronger appeals and customize its enforcement when the automated tools catch real users in their net. Civil society organizations, such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation, have also cautioned that name-based heuristics may produce unfair results for individuals who have common or popular names.

Identity verification was updated — Meta offers a range of verification and business authenticity tools — and small companies frequently use basic business pages and ad accounts. When a page is taken down without notice, the consequences are fast and furious: ad spend is wasted, leads disappear, and the appeals process can be murky.

What’s at stake, beyond a funky headline

At one level, this is a novelty: Mark Zuckerberg vs. Mark Zuckerberg. In essence, it points to a recurring problem for social networks running at planetary scale — how to tell fraud from coincidence without mashing up real users in the gears.

Facebook and Instagram serve as storefronts for small law practices, clinics and local businesses. Turning off a page can seem like the digital equivalent of locking the door during business hours. If a case of name collision could significantly lead to impersonation filters being aroused, the example may argue in favour of remedies like better identity checks for verified advertisers, faster human review when a false positive is repeated, or issuing clear credits when paid campaigns are obviously disrupted by a mistaken enforcement action.

Legal observers point out that platforms have a wide range of discretion to moderate under the terms of service, but are also subject to consumer protection scrutiny when paid services are disrupted without remedy. The result could affect how platforms record and make amends for takedowns that pause paid campaigns — especially when the user can show a verified identity.

The broader signal to platforms and professionals

There are a lot of Mark Zuckerbergs or John Lewises or Michael Boltons in the real world. Now that digital advertising is table stakes for small companies, platforms will be pushed to refine systems that equate fame with fraud. A single, name match of a high-profile entity, should not stand between verifiable business documentation, consistent account history, and, for example, our previous investigations and determinations that enforcement was mistaken.

For the moment, the suit from the Indiana attorney elevates a running gag to a legal question of moderation, identity and accountability. If it also leads to clearer rules around advertiser protection and faster remediation for false positives, a lot of less-famous names will benefit, no matter how famous their look-alikes may be.