Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro brandished the phone and declared it impervious to American sabotage, and helping to project Chinese-made communication devices as a ward against, among other things, the world’s most efficient spies. The remark is politically potent. It also misunderstands how smartphone security — and nation‑state hacking — actually work.

Maduro’s brag plays to the wider geopolitics surrounding Chinese technology and U.S. intelligence. But the technical fact is blunt: no modern phone can be “immune from compromise,” particularly when a well‑resourced adversary is involved, according to the report. Even Huawei’s high‑end ‑end handsets and HarmonyOS, the software intended to succeed Android, are no exception.

A message of politics meets a reality of security

Leaders frequently brandish devices totems — of sovereignty, of technological independence, of resistance to surveillance. But symbolism does not decide cybersecurity; it is a world of nudges, bugs and patch cycles. When the adversary is a top‑tier intelligence service, the calculus shifts still more. Resources pay for time, and tooling and access.

As a practical matter, saying a phone “can’t be hacked” is like saying a safe “can’t be cracked.” You don’t have to break the steel every time to get through it; you just need to find the weak hinge, the guard who’s not paying attention, the side door. On phones, such weak points could be the baseband modem, browser, messaging stack, app ecosystem, peripheral drivers or the update channel.

What the record indicates about Huawei and U.S. spies

That U.S. intelligence has targeted Huawei systems before is well documented. Documents leaked by Edward Snowden revealed the National Security Agency penetrated Huawei’s front-runners for networks to observe how they work and to be able to exploit them for future networks. Internal N.S.A. documents said the mission was an effort to target for penetration network equipment, including Internet routers, that is being used by millions of people. The document notes that this is a “team sport.” Prosecutors in the United States have alluded to the China-based company in court proceedings.

Intelligence agencies examine vendor hardware and software, including Huawei, specifically to find vulnerabilities and write exploits. China’s government and its state‑linked researchers have, in turn, blamed the NSA for breaching Chinese networks and telecom infrastructure. None of this makes a specific Huawei phone a bad apple; but it does indicate that if spies are involved, phones are a ripe piece of espionage fruit and both sides sink a lot of resources into finding cracks.

HarmonyOS and the patch pipeline

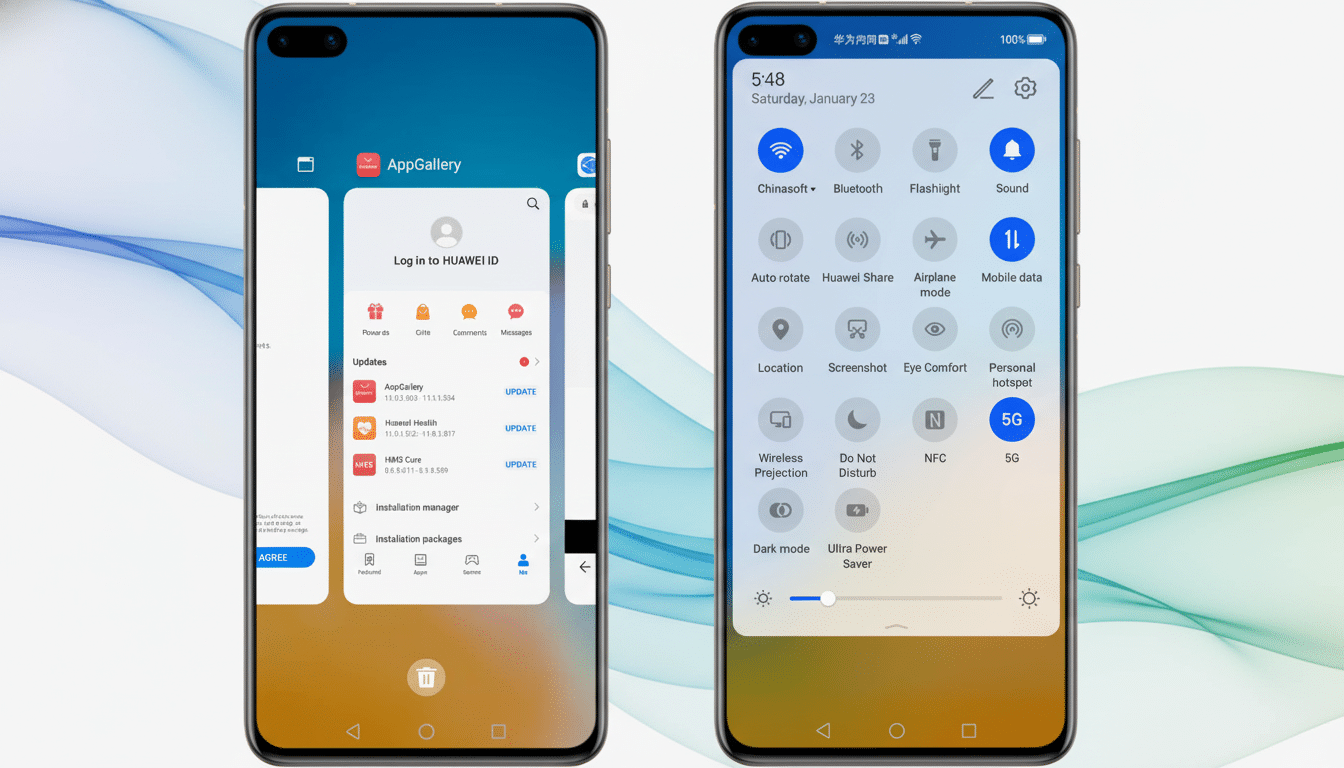

Huawei’s smartphones have an offshoot of HarmonyOS that has developed quickly, straying farther from Android while maintaining compatibility layers. Rapid evolution is a mixed blessing. New code reduces reliance on U.S. tech, but churn can introduce new bugs. Security researchers consistently caution that big rewrites and new interfaces create attack surfaces ripe for exploitable mistakes.

Advisories from Huawei itself spell out the scope of the job. In a recent bulletin, the company detailed 60 HarmonyOS vulnerabilities that were fixed in one go, 13 of which were rated as high severity. Huawei tells its customers that it issues monthly patches for most of its flagship devices, but also warns that coverage and timing may vary depending on the model and whether someone’s carrier has its own software or restrictions. That variability is important, as patch lag is often the thing that makes a bug into a breach.

But the attack surface isn’t just the operating system. Baseband processors that manage cellular communications have traditionally contained vulnerabilities across vendors, which can be exploited to compromise them over the air in some cases. Browser engines, media parsers, and Bluetooth stacks are common origins of zero‑click bugs. None of this is particularly unique to Huawei; it’s the shared fate of complex, interconnected devices.

No unhackable phones, only harder targets

Commercial exploit brokers have paid seven‑figure sums for reliable, zero‑click chains for both Android and iOS—indicating that combat-ready, high-end smartphones could be compromised when the motivation was there to cover the expense. Government teams have larger budgets and legal authorities, and they have the aid of classified vulnerability stockpiles and purpose‑built tooling.

Defensive tech has improved. For instance, hardware‑backed encryption, secure enclaves, memory safety advancements, and exploit mitigations increase the level of effort required by attackers. Huawei claims to offer the same protections in its flagship devices, and at least some aspects, such as encryption at rest, have been verified by independent laboratories. Nevertheless, real-world cases — be they with spyware on other brands or baseband bugs — prove that “harder” is not “impossible.”

Why the claim matters, and what users should do

Maduro’s pronouncement is more geopolitical signal than technical judgment: an endorsement — or shows of support — for Chinese technology coupled with a swipe at American surveillance. Yet you overstate security at your own peril. The moment anyone thinks one of these devices is invulnerable, they stop updating it, they install unvetted apps and they ignore basic operational security — all of which erase even the best-engineering advantages.

For average users, the math is simple: update the phone, stick to official app stores, refuse to allow side‑loading where you can, and treat unsolicited links or attachments with wariness. For high risk users like politicians, journalists, and activists, the guidance is even more restrictive: Run as few apps as necessary, break out of accounts, and maybe even consider specialized mobile threat defenses. Above all, know that your threat model is the enemy. If the enemy is a nation‑state, every smartphone on the planet is a target, including Huawei.

The bottom line. Huawei is capable of making devices with modern protections, but the idea that American spies “can’t” hack them is a political slogan, not a security promise. In cybersecurity, confidence is a warning; only vigilance and timely patching have any hope of delivering.