Madrid’s Orbital Paradigm is stripping back one of spaceflight’s most byzantine feats — bringing hardware safely through hypersonic reentry — without the price tag that normally comes along with it. The early-stage company envisions small, purpose-built capsules that will beat current return systems and enable faster and more frequent trips for research in microgravity and on-orbit manufacturing.

Why smaller, simpler capsules could win

The team’s thesis is simple: Most customers don’t require a crew-rated spacecraft or a cargo hauler the size of a compact car. What they need is routine, lower cost access to minutes or days of microgravity, and then a reliable return. The Orbital Paradigm approach is one a minimalist capsule that flies light, allows for no slack margins, and sticks to mission-essential functions.

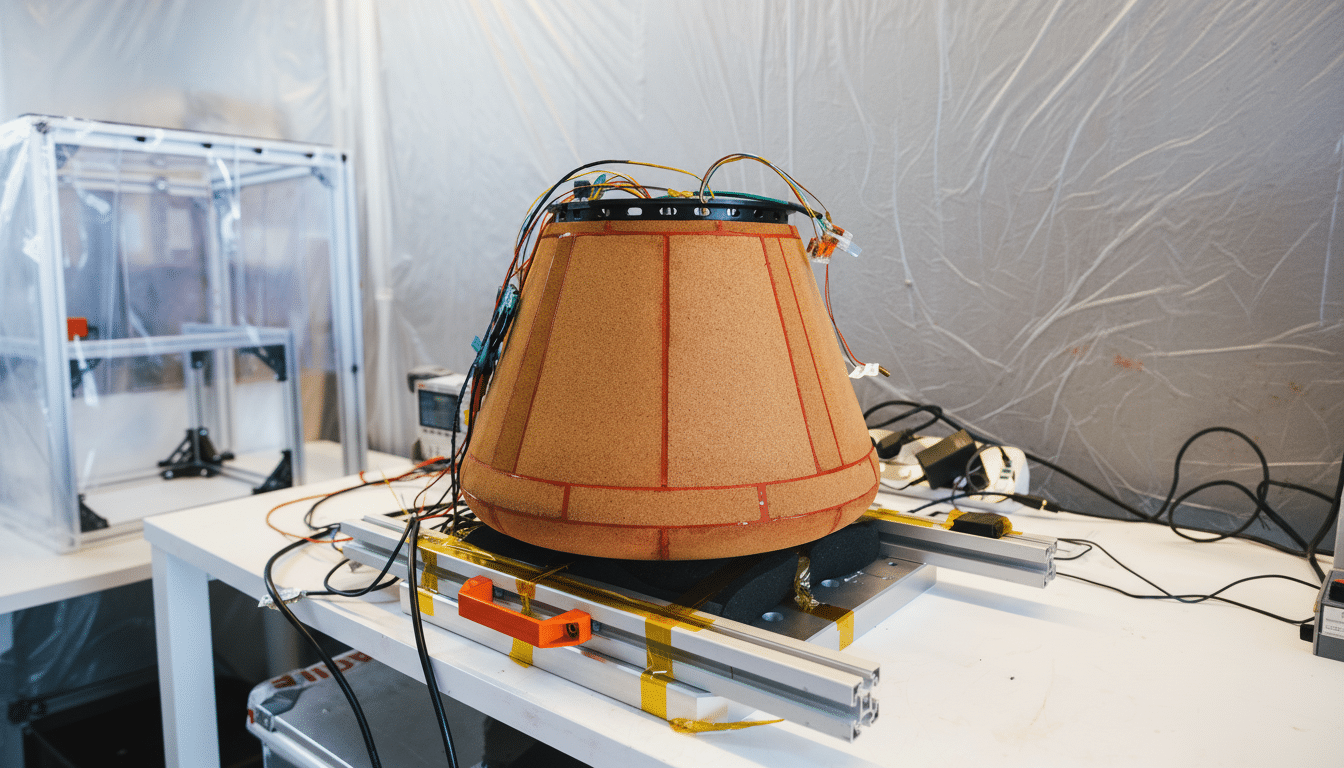

Their first vehicle, a proof of concept called KID, is approximately 25 kilograms and has a span of about 40 centimeters. There is no propulsion, no intricate guidance system, no costly recovery campaign. In the near term, the idea is to get away from a launch vehicle, function in space, endure maximum heating and send out at least one “I made it” ping before, you know. That’s intentionally austere, but it collects the thermal and aerodynamic data required to validate the design at a fraction of its normal cost.

This “minimum viable reentry” approach reduces cost in three high-burn areas: mass and complexity (no deorbit propulsion or precision landing), ground infrastructure (no dedicated recovery ships or aircraft on the first flight), and certification burden (demonstration-class risk posture instead of crew or cargo ratings).

Smaller capsules fly better aerodynamically too: a small ballistic coefficient generates earlier drag and less peak heating than a larger more dense body.

The first flights: test, learn, then save

The maiden mission has three payloads manifested, from French space robotics startup Alatyr and Leibniz University Hannover in Germany.

The company added that a third customer will be revealed closer to launch. The flight will be booked with an unnamed launch provider and represent the startup’s first on-orbit hardware demo.

_Recovery isn’t the goal this time; data is._ The capsule is intended to survive the most brutal phase of reentry and verify communications, offering real world heating and loads for comparison with computer simulations. That data feeds into a follow-on campaign where Orbital Paradigm is planning to add propulsion and a parachute to land in a controlled splashdown.

That second mission, which aimed to make a controlled descent into the Azores, matches Portugal’s effort to build a spaceport in Santa Maria led by its national space agency. Although the initial version emphasizes microgravity “research windows” (vs. long-term orbital footprints), adding in recovery means customers can iterate fast on materials, biotech and components – something that both the ISS National Lab and European research programs repeatedly identify as key to maturing space-enabled products.

A crowded field and a higher reentry bar

The company joins the race to develop a more competitive transatlantic service. In the US, Varda Space Industries launched a re-entry and landing of a commercial capsule, which has secured a re-entry license at the US Federal Aviation Administration and demonstrated a complete end-to-end flow from orbit to ground. For Europe, the Future M2M and BepiColombo investigations included the controlled reentry of a test vehicle in a modular platform for future operational services. Inversion Space, among others, is also developing logistics, defense and research-sized rapid-return containers.

Where Orbital Paradigm diverges is in cost discipline and cadence. By doing away with the mass and operational footprint of big capsules, the team is targeting a price point that would make it economically viable for several flights per year for a single customer — a pattern common in biotech and advanced materials, where the protocols insist on frequent, repeatable runs. Thaikourey said that industry roadmaps, such as those established by ESA, identify microgravity-enabled processes (crystal growth, fiber optics, organoids) that require iterating on experiments, not sending one-and-done missions.

Europe’s skinny way, U.S. tailwinds

Orbital Paradigm has collected around €1.5 million in seed funding from backers such as Id4, Demium, Pinama, Evercurious, and Akka. That’s modest by aerospace standards. U.S. peers frequently supplement venture rounds with nondilutive government contracts—via programs like SBIR and defense hypersonics projects—that can add tens of millions in R&D spending. “Most European start-ups are more used to not having such injections of other people’s cash, generally using private money and selective national, or ESA, grants which can encourage closer engineering cycles, as well as an earlier commercial focus.

Scant funding can serve as a forcing function. Building to sell from the very first day, the product is defined around pragmatic needs: adequate thermal protection rather than tailored tiles, basic avionics rather than redundancy-rich architectures, and flight test sequences that emphasize retired risk metrics, not station keeping. It’s a different rhythm than the flagship capsules, but one that’s increasingly in tune with those that use microgravity.

What success would look like for orbital return

If KID’s flight proves out the models, Orbital Paradigm’s follow-on steps, adding deorbit capability and recovery while remaining small, may lower the bar for return from orbit again. Think of it as an airfreight envelope for space: simple, standardized, and built for speed rather than size.

For researchers, that could mean faster design cycles and clearer unit economics for startups. Instead of reserving the one or two scarce slots on a bus-sized vehicle, you’d reserve quality time to run multiple experiments per year, so that you could isolate variables and progress from proof of concept to product qualification. Spacefuel:Menchikov Space agencies and their university partners would have a new platform alongside the ISS and forthcoming commercial labs, “especially for short-term experiments”.

Reentry will forever be merciless physics. But by defining the mission more narrowly, to what many actual users really need — and demonstrating the same with a deliberately spartan first flight — Orbital Paradigm hopes to make the point that it is less moonshot than a matter of right-sizing the problem.