After three decades with Linus Torvalds at the helm, the Linux kernel community has outlined a formal continuity plan that spells out how a new top-level maintainer would be chosen if he steps aside or becomes unavailable. It’s not a named successor, but a concrete process—designed to safeguard mainline development and calm the long-standing “bus factor” anxiety around the project’s single point of final approval.

The plan emerged from discussions among senior maintainers at the Linux Kernel Maintainers Summit in Tokyo and was drafted by veteran contributor Dan Williams. Rather than anointing an heir, it defines who convenes, how candidates are evaluated, and how the decision is ratified to keep merges and releases moving without drama.

- Why This Succession Planning Moment Arrived

- How The Linux Kernel Succession Would Work

- Who Might Step In To Lead The Linux Kernel Project

- The Bus Factor And Linux Governance Options

- Maintainer Pipeline And Long-Term Sustainability

- What It Means For Linux Users, Vendors, And Partners

- Bottom Line: A Pragmatic Plan For Continuity In Linux

Why This Succession Planning Moment Arrived

Several forces converged. Torvalds recently renewed his contract with the Linux Foundation, prompting the Technical Advisory Board to revisit long-term governance and risk. Maintainer fatigue has also become a recurring concern, with senior leaders noting the cohort at the core is “getting gray,” and onboarding fresh maintainers into high-trust roles remains hard work.

The conversation is not a retirement teaser. Torvalds continues to review and merge code at his usual cadence. The objective is pragmatic: reduce key-person risk in a codebase that underpins everything from cloud infrastructure to smartphones.

How The Linux Kernel Succession Would Work

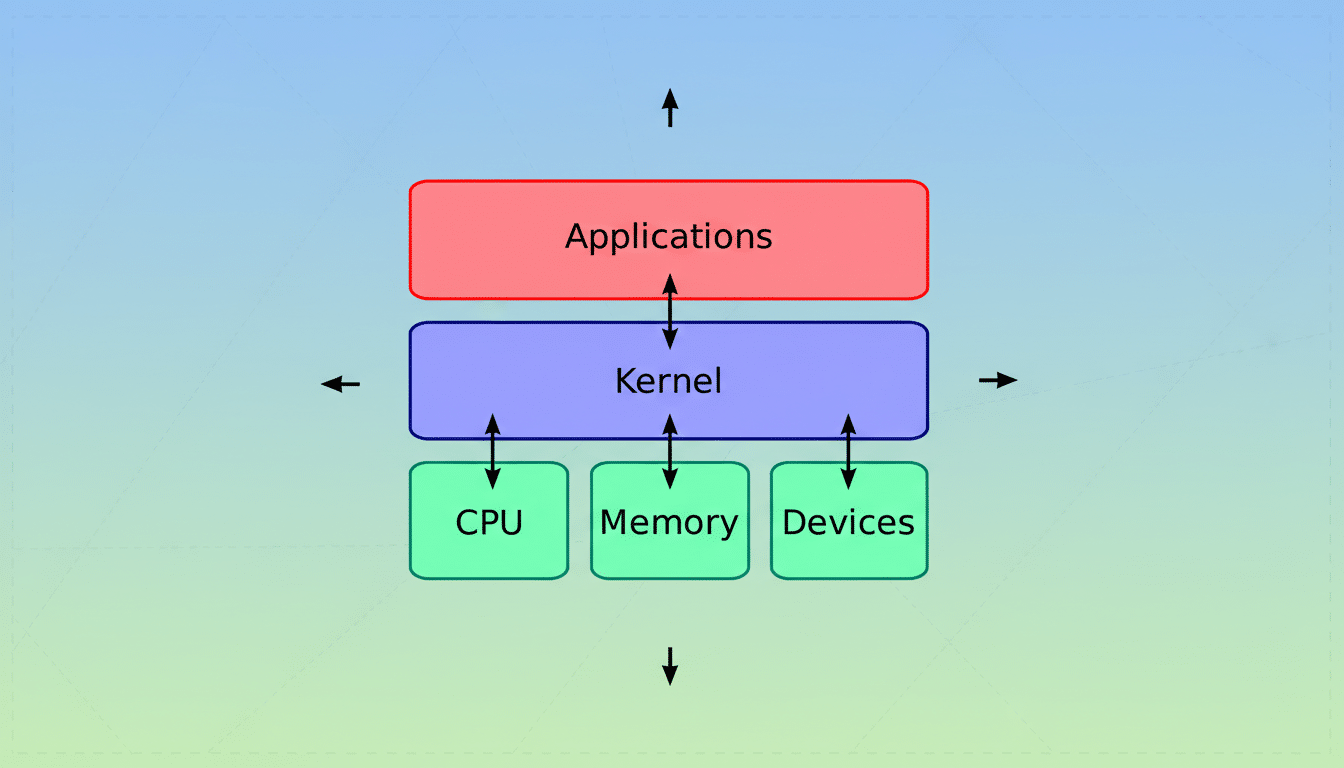

The continuity document sketches a selection conclave of trusted maintainers to choose one or more people to manage the top-level tree. The group’s mandate is to maximize long-term project health, not simply pick the most senior engineer. Criteria emphasize demonstrated technical judgment, community trust, and the ability to keep weekly release trains on time.

The framework anticipates two paths: a rapid response for emergencies and a deliberative handover for an orderly transition. It stops short of fixing the model to a single “BDFL” replacement, leaving room for a shared role if consensus points there.

Who Might Step In To Lead The Linux Kernel Project

While the plan avoids naming names, one figure inevitably surfaces: Greg Kroah-Hartman, who runs the stable branch and briefly covered for Torvalds during his 2018 hiatus to reset community conduct. Historically, the top maintainer mantle has shifted among trusted hands—think Andrew Morton and Alan Cox—and any future choice will hinge on trust built through years of visible, level-headed decision-making.

Industry voices like Dirk Hohndel have noted the need for experience and continuity, while acknowledging that a council model could distribute load and extend longevity. The plan keeps both options open.

The Bus Factor And Linux Governance Options

Today, torvalds/linux.git still depends on one final arbiter, which means the bus factor is effectively one. The new process lifts that risk by making the path to a successor explicit. Other ecosystems offer precedent: after Guido van Rossum stepped back, Python moved to a Steering Council model that preserved velocity and legitimacy. Linux has different workflows—dozens of subsystem trees, an 8–10-week release cadence, and a relentlessly high patch volume—but the principle of predictable governance translates.

Linux Foundation reports show more than 15,000 developers from over 1,300 companies have contributed since 2005, with typical releases incorporating patches from 2,000+ individuals and 10,000–15,000 commits. With a codebase exceeding 30 million lines, stability depends on sustained, collective stewardship.

Maintainer Pipeline And Long-Term Sustainability

Veteran maintainers have flagged the need to broaden the bench. Recruiting new subsystem leaders is slow because trust is earned through years of consistent reviews, regressions handled gracefully, and thoughtful reverts when needed. Programs such as the Linux Kernel Mentorship initiative and Outreachy help develop contributors, but the jump from contributor to maintainer remains steep.

Large stakeholders—cloud providers, chip vendors, and enterprise distros—are investing in kernel teams to keep that pipeline healthy. Companies like Intel, Red Hat, Google, and Collabora regularly field maintainers and reviewers, spreading the load across corporate sponsors and independent contributors alike.

What It Means For Linux Users, Vendors, And Partners

For most users, nothing changes now. Mainline development continues as usual, and long-term support kernels remain the backbone for distributions and embedded systems. The real value is risk reduction: the project now has a map for preserving cadence, release quality, and subsystem autonomy, even if an unexpected transition is required.

Vendors depending on stable APIs and security response windows gain confidence that the merge window, release candidates, and LTS backports will proceed without governance drama. That matters for Android device makers, hyperscalers, and enterprise environments where Linux is mission critical.

Bottom Line: A Pragmatic Plan For Continuity In Linux

Torvalds remains firmly in charge, but the kernel community has finally written down how to carry on without him. By separating process from personality, the plan acknowledges reality, strengthens institutional memory, and ensures that Linux’s most important project is bigger than any single individual—exactly as open source intended.