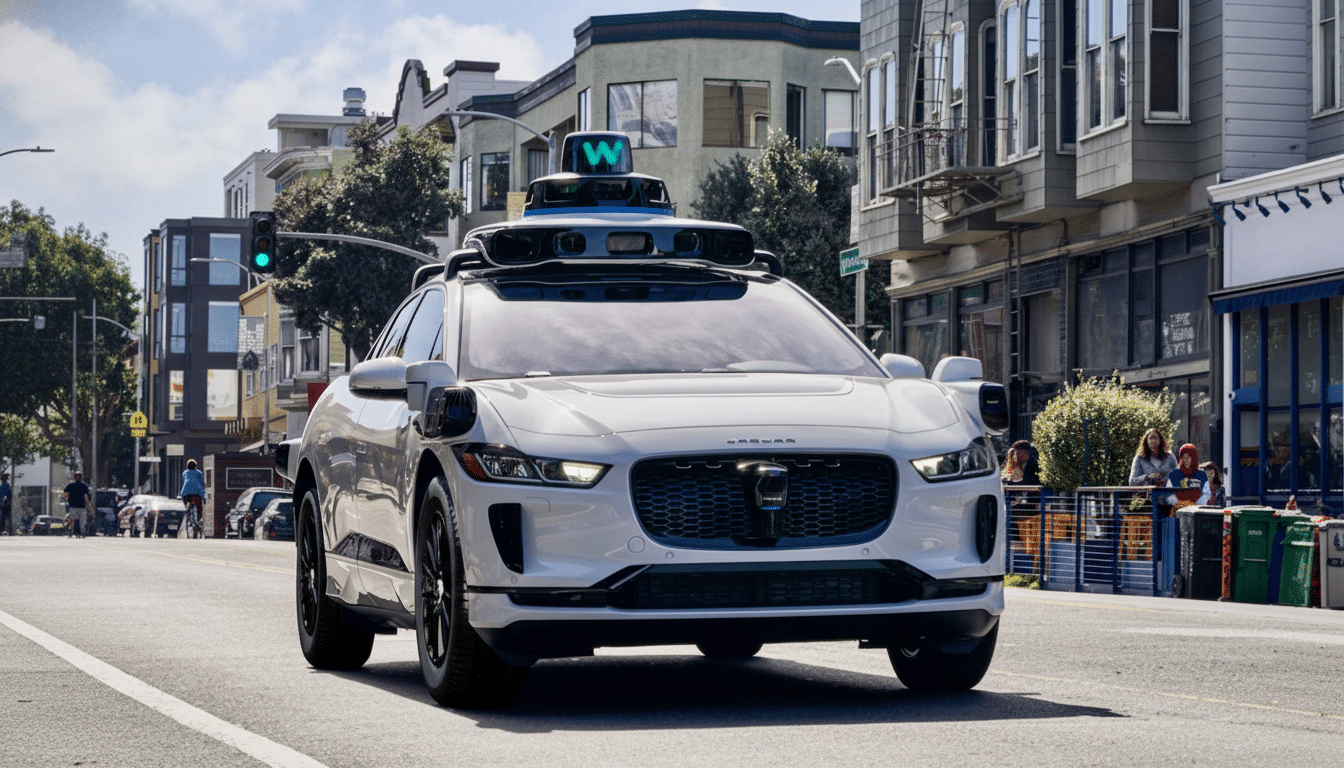

A neighborhood cat that went by the name of KitKat was hit and killed by a Waymo robotaxi, while San Francisco leaders are demanding to have a voice in where driverless cars roam.

The outcry is visceral and neighbor-to-neighbor. The power to act is not. Under California’s model, the city may not unilaterally halt Waymo cars even in the wake of a tragedy that has torn at the fabric of a neighborhood.

- Why City Hall Can’t Just Pull the Plug on Robotaxis

- The New Push for Local Control Over Driverless Cars

- What the Data Says About Robotaxi Safety

- The Patchwork Problem for the Bay Area’s AV Services

- What Executives and Regulators Are Signaling

- Might Washington Call the Shots on AV Deployment

- The Bottom Line for San Francisco and Waymo’s Future

Waymo has admitted responsibility for the accident, expressed its condolences and made a donation to an animal welfare organization. But as mourning residents press for accountability that moves beyond words — and find out how little control City Hall actually has over robotaxis on its streets.

Why City Hall Can’t Just Pull the Plug on Robotaxis

California State led the centralization of federal oversight on autonomous driving. Testing and deployment of AVs are regulated by the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) while commercial ride services and fare collection are governed by the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC). That state-level preemption means San Francisco has the power to issue tickets to any driver — human or not — who violates traffic laws, but it cannot ban a permitted robotaxi service from hitting the streets.

The thinking is this: A trip from San Francisco to Burlingame spans multiple jurisdictions in minutes. State regulators say uniform rules prevent a mishmash of compliance that might suddenly exclude passengers at city borders and hamper the coordination of emergency responses.

The New Push for Local Control Over Driverless Cars

District 9 Supervisor Jackie Fielder (in photo below) is calling on us to keep the pressure on Sacramento and insist that lawmakers allow counties to vote on whether AVs can drive in their area. The effort is reminiscent of SB 915, a bill from state Sen. Dave Cortese that would have permitted local governments to grant AV permits, cap fleet sizes and set fare policies. The bill won backing of the Teamsters, the California Professional Firefighters Association and the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor following high-profile incidents, such as a Cruise robotaxi colliding with a fire truck.

Representatives of business and disability advocacy groups had warned that the measure would create a patchwork of rules that could cut into access and rob residents of reliability. The bill was withdrawn in the face of intense opposition, but the political pressure for “clear local oversight” has not waned — especially after KitKat’s death.

What the Data Says About Robotaxi Safety

Waymo says that its riderless fleet has driven tens of millions of miles, most in San Francisco, with much lower crash rates than human drivers. The companies tout reduced accidents overall compared with human baselines, including 91% fewer crashes causing serious injury or fatality, 80% fewer crashes that cause injury and heavy reductions in crashes involving pedestrians, cyclists and motorcyclists.

No public breakouts are available for crashes with animals. Insurer State Farm says drivers file about 1.7 million vehicle-animal claims a year in the United States, most for deer; California is considered low risk. Physics remain physics: small animals can dart out from cover into the path of a vehicle, and perfect detection is scant help when there’s hardly any room to stop at low speeds if that object now appears beneath the bumper.

Context is sobering. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration tallies more than 39,000 traffic deaths a year across the United States. Speed is a factor in 29% of deaths, alcohol in 30%, and almost half were unbelted. AVs don’t speed or drink and can be programmed not to move until seatbelts click — so large safety gains are plausible even if zero risk is unattainable.

The Patchwork Problem for the Bay Area’s AV Services

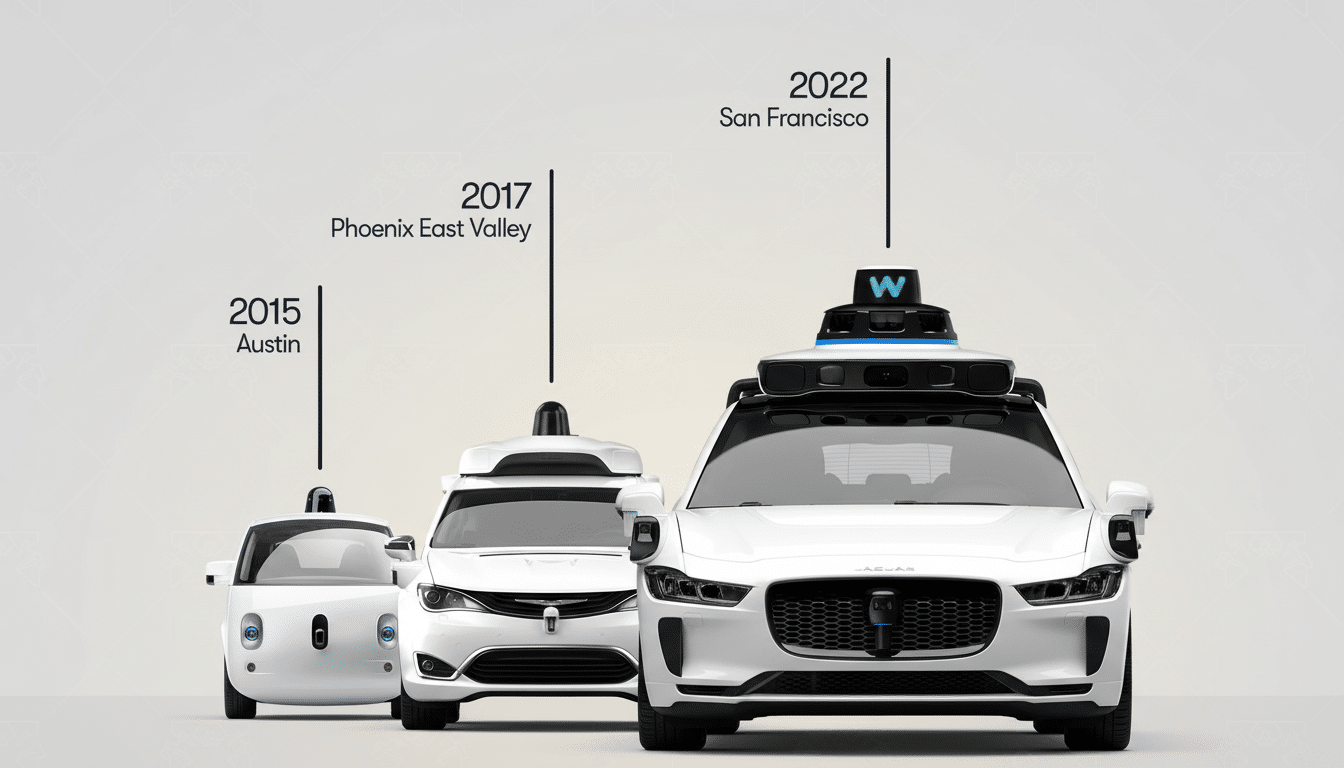

The Bay Area encompasses nine counties and over half the cities. Waymo has partnerships across San Francisco, Los Angeles and has begun expanding its reach all the way down to San Jose. When every jurisdiction is free to choose its own hours of operation, cap on fleet size or no-go zones, service could easily become unreliable.

Geofenced boundaries would necessitate “deadheading” detours, trap wheelchair users at city lines and return the arbitrariness of late-night transit conditions that cause BART to stop running before bars close.

That’s not to say that the locals are without power. Cities can influence curb management, designate pick-up zones, mandate construction-site coordination and negotiate data-sharing that flags sticking points — say, certain alleys or bike corridors or nightlife meccas. Those micro-policies impact safety in ways that do not contravene the authority of the state.

What Executives and Regulators Are Signaling

Waymo co-CEO Tekedra Mawakana has said that companies must candidly discuss safety records, as well as crashes. After Cruise’s DMV-ordered permit suspension and the subsequent pause in operations, regulators made clear that they would step in when there was evidence to justify doing so. The message to industry is quite clear: Continue publishing data, perform better in increasingly crowded urban applications and move cautiously as service areas expand.

Might Washington Call the Shots on AV Deployment

At the federal level, pre-emption could eventually streamline the patchwork across the country. NHTSA sets vehicle safety standards, but the agency does not control how and where vehicles can be used; that’s up to the states. Previous congressional attempts at uniformity in AV deployment have sputtered, leaving states like California to play referee. Until Congress acts, San Francisco’s proper role involves Sacramento, not declaring its own ban.

The Bottom Line for San Francisco and Waymo’s Future

San Francisco can’t halt Waymo because state regulators hold the keys to AV deployment and to ride-hailing authority. Local leaders can turn grief into action, some quite practical (like targeted curb rules or better incident reporting) and others entirely pragmatic (pressure for stricter statewide standards), while the larger safety math shows major cutbacks in human-caused harm. Justice for KitKat, in policy language, probably won’t come in the form of a ban. It will be wiser statewide rules and better local coordination that make the streets safer for one and all — on two legs or four.