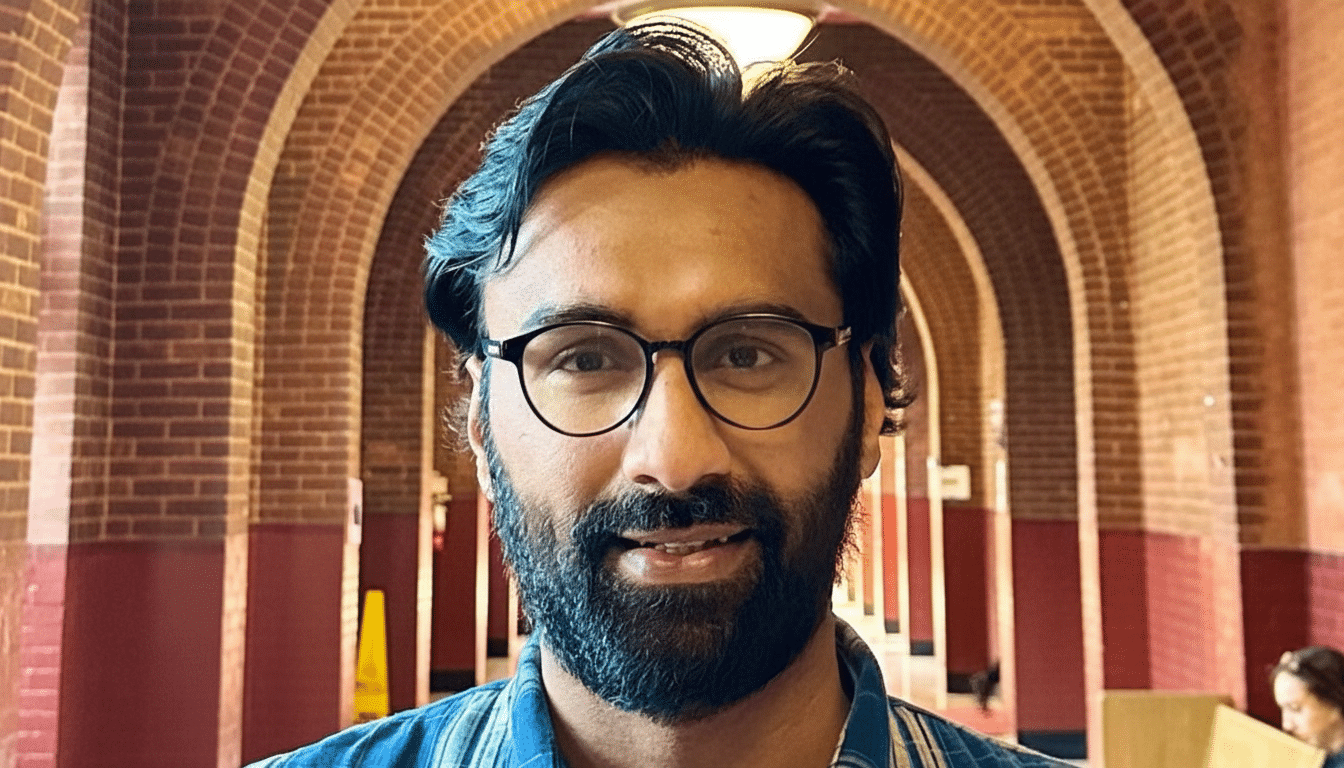

A federal judge has temporarily barred the Trump administration from arresting or deporting Imran Ahmed, chief eXecutive of the Center for Countering Digital Hate, a high-profile social media watchdog organization, in a case testing the limits of executive power over lawful permanent residents and freedom to scrutinize social media platforms.

Ahmed is one of five researchers and regulators that the State Department has taken action to block from visiting the United States, considering them “radical activists and weaponized NGOs,” according to The New York Times. The court’s order maintains the status quo as the challenge plays out, automatically suspending an effort that critics say would censor research into online abuse and disinformation.

Ahmed, a U.K.-born researcher holding a U.S. green card, resides in the country with his American wife and child. The government’s action, he said in an interview with PBS News, should be seen as part of a larger campaign by powerful tech interests to suppress independent scrutiny.

Why This Researcher Is a Target for Government Action

Ahmed is the head of the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH), a nonprofit that routinely publishes industry reports on how hate speech, harassment, and fake news infect major platforms. For example, the group’s “Disinformation Dozen” study contended that a small number of big super-spreaders accounted for an outsize proportion of anti-vaccine lies — a finding that got a lot more public and policymaker attention and led companies to reconsider enforcement policies.

His work has also dovetailed with the business interests of platforms. X, which is owned by Elon Musk, sued the group for its research methodology and claims about ads running alongside extremist content. A federal judge in California dismissed the case in 2024; it is under appeal. The bruising litigation highlighted the stakes for watchdogs whose findings can guide advertisers and mold public perception of brand safety online.

The administration’s decision to exclude Ahmed and others comes at a challenging moment already for disinformation research. Academic centers and nonprofits have been served subpoenas, sued, and subjected to political pressure over partnerships with platforms on election integrity and abuse prevention.

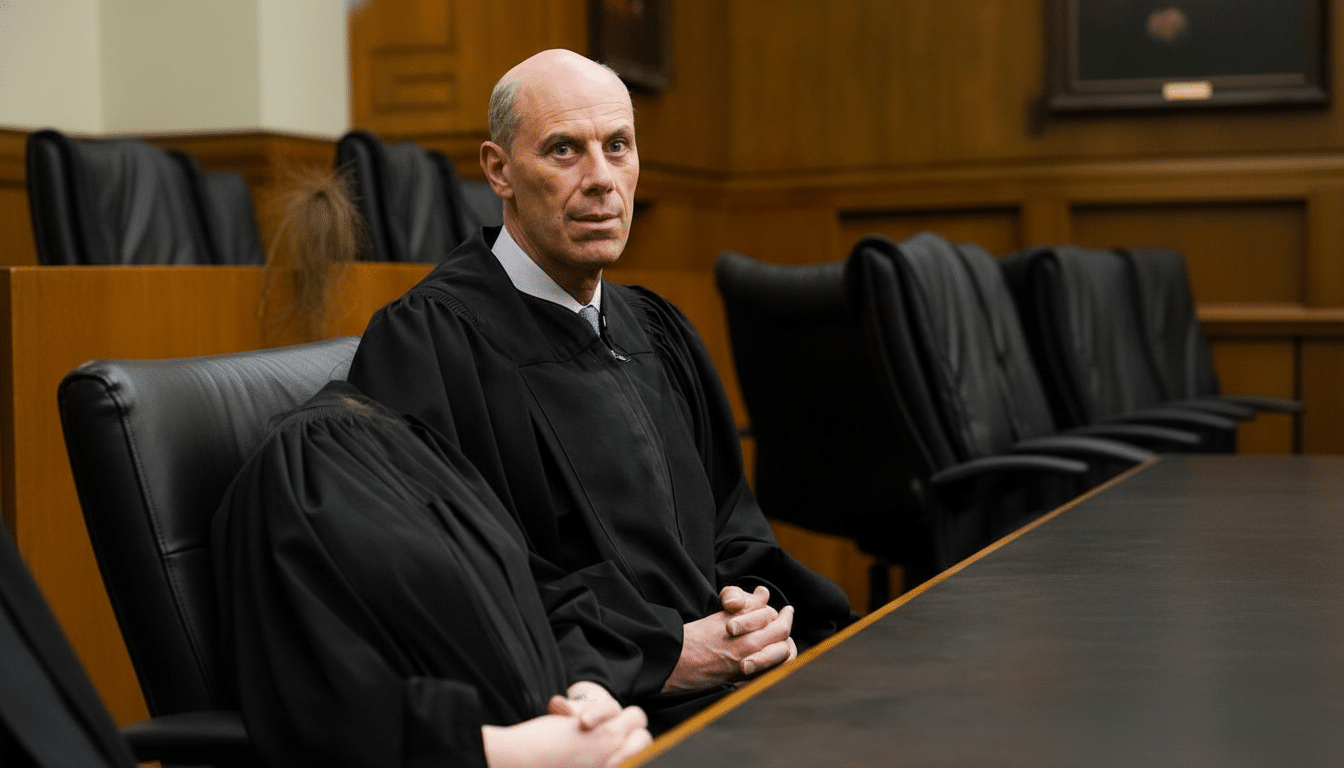

The Legal Questions Around Deportation and Due Process

Legally, the case asks whether the executive branch may categorically exclude or remove a lawful permanent resident based on broad national interest claims and how far the State Department’s exclusion authority reaches within the United States. Green card holders have due process rights; removal usually occurs in immigration courts, not through unilateral executive acts.

The judge’s 30-day temporary restraining order halts any arrest or deportation, at least signaling preliminary concern that the government’s reason may collide with constitutional protections. Civil society organizations, among them the Knight First Amendment Institute, have cautioned that severe steps against researchers risk leaving a chilling effect on inquiry fundamental to platform accountability and public understanding.

For the government, the case is a test of its contention that some researchers and entities have crossed over from analysis to coercive campaigns that “pressure” platforms into suppressing viewpoints. Secretary of State Marco Rubio invoked that framing in announcing the exclusions, accusing them of gaming content policies under the rubric of safety.

Platforms, Pressure, and the Business of Moderation

Independent audits of harmful content can send companies into a tailspin, and quickly. And major brands have pulled groups of ads dozens or hundreds of times when they are reported as appearing next to slurs, other hate speech, and extremist posts. The pauses have an echo: They can shave quarterly ad revenue and prompt policy tweaks around brand safety — including on other platforms after high-profile controversies.

It’s that feedback loop that helps explain the conflicts between watchdogs and the platforms. Without outside measurement, companies skimp on counting or punishing the worst material, especially if they serve engagement metrics. Platforms, however, argue that outside studies suffer from methodological weaknesses or unauthorized access to data and that heavy-handed pressure can tip into censorship.

It’s also increasingly up to the courts to referee those lines. The rejection of X’s suit against CCDH was based in part on the protections regarding speech and research on subjects of public concern. And courts have whittled away broad theories that government coordination with the platforms necessarily amounts to a First Amendment violation, focusing on proof of coercion instead of mere conversation.

What Comes Next in the Legal Fight and Research Climate

The immediate question is whether the administration will defend its exclusion decision based on evidence that courts find persuasive, or pare back its action. Ahmed counts the restraining order as a practical victory, albeit temporary: It allows him to remain with his wife and children while pursuing their case.

More broadly, the battle will be a symbol of whether it is safe for researchers to publish inconvenient findings about big platforms. If the government can refocus immigration tools to go after critics, advocates warn, the risk calculus for cross-border scholars and nonprofit leaders will shift overnight.

Regardless of how the court rules, the case will shine a spotlight on a quintessential tension of the digital age: where to draw the line between protecting open debate and insulating harmful speech. Independent research — so messy, so contested, and so often inconvenient — is one of the few levers the public has to see how that line is drawn.