A popular police program that put Sacramento residents under near-constant surveillance in their own homes — secretly recording and then analyzing every noise at more than 200 locations throughout the city — was ruled unconstitutional last week by a U.S. court. The ruling applies to an information-sharing pipeline between the Sacramento Municipal Utility District and city enforcement teams, which relied on near-real-time electricity data as part of efforts to target suspected illegal cannabis grows.

What the Court Found About SMUD’s Data Disclosures

By a 6-1 vote, the court held that SMUD as a publicly owned utility had violated confidentiality norms under California Public Utilities Code section 8381 by making general use of customer consumption data absent case-specific investigations. The judge ruled that the utility and the city had constructed an arrangement that went beyond a typical provider-law enforcement relationship, and that requests from the city were not connected to active investigations — two key elements in finding the data disclosures illegal.

The ruling was in response to a case filed by the Asian American Liberation Network and two Sacramento residents, who were represented by the Electronic Frontier Foundation. “The utilities cannot wholesale boot that data to the police without individualized suspicion or judicial process, and effectively the court’s opinion supports that view,” EFF wrote.

How the Electricity Data-Sharing Program Operated

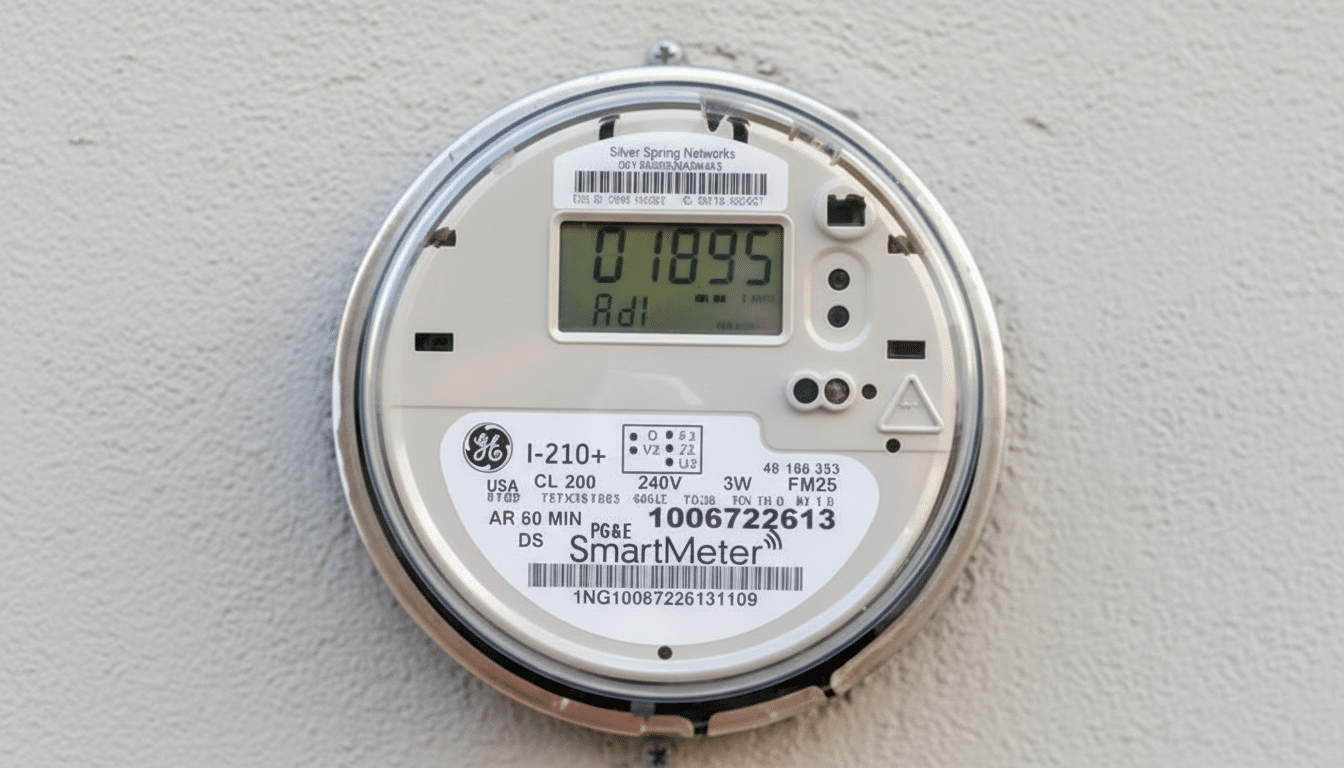

SMUD started taking 15-minute snapshots of residential electricity use in 2009, as required for smart meters throughout the state. The Cannabis Compliance and Investigations Unit within the city sent out quarterly requests for such account lists, organized by ZIP code, according to court filings. And residents appeared on the list if they were using at least 2,800 kilowatt-hours of electricity a month — roughly five times what a typical California home uses in a month (about 550 kWh per month, according to the Energy Information Administration).

Records were scanned for red flags, such as a suspicious case of theft or meter tampering, and the results were shared with city officials when requested. There may be spikes in electric load that correspond to energy-hungry illegal grows, but they can just as likely signal purely legal changes — installation of a heat pump, addition of an EV or hot tub, operation of medical equipment — which is why California’s new privacy rules should have discretion built into them.

Civil Rights Concerns and Alleged Bias in Enforcement

The Asian American Liberation Network argued that the dragnet unfairly affected Asian residents, pointing to city fine data they say showed 85% of penalties falling on people of Asian descent. Though the court’s decision rested on statutory privacy rights rather than equal protection claims, the disparity statistics sharpened concerns about covering all while casting dragnets widely and can make statistical bias permanent, in the name of efficiency.

Privacy groups have long argued that granular utility data can provide insight into daily rhythms — when a light is usually switched on, for example, or when no one is home and the residents are likely sleeping — and be utilized toward investigations far beyond energy theft or safety.

That’s one of the reasons the California Public Utilities Commission and state law strictly limit sharing usage data outside a provider — including with police — unless the customer consents, it’s pursuant to a warrant, or in other specific emergencies.

What the Ruling Means for Utilities Across California

The decision works as a wake-up call for publicly owned utilities across California. Under section 8381, providers must establish and enforce privacy policies that severely restrict access to usage data. In the wake of this decision, utilities will probably adjust their law-enforcement policies — enshrining warrant requirements, restricting search terms, recording responses (from ‘Yes’ to ‘No’) and training employees to say no to broad ZIP code requests not based on individualized suspicion.

The message to cities is just as unequivocal: if investigators want energy data, they must come with particularized requests based on a specific investigation, not quarterly rundowns of high-use addresses. Post-legalization enforcement against cannabis has often relied on electricity spikes to identify unlicensed grows, but the court signaled that efficacy cannot supersede statutory privacy protections.

Privacy on Smart Meters, Beyond Sacramento

At this point, smart meters are everywhere — EIA says that about 80% of U.S. electricity customers had one in the last report, so clearly drawn rules are essential. Sensor and reading intervals are equally sensitive; indeed, even federal courts have recognized that interval energy data of the kind Kittleman sought here may be subject to Fourth Amendment protections, despite the fact that in that case, a compromise program was upheld under proper limiting protocols.

California’s structure has been seen as one of the most stringent for quite some time, because of Public Utilities Code sections 8380–8381 and CPUC privacy decisions that mandate utilities to “minimize sharing” and protect customer data.

This ruling puts enforcement teeth on those policies, and sends a message that utilities can’t serve as investigative proxies.

The Bottom Line on Electricity Data and Surveillance

The court’s order closes off a powerful, tech-assisted surveillance shortcut and confirms that electricity usage records — ultra-granular, revealing and easily misread — are not fair game for state dragnet policing. Stories of residents who have mismanaged water resources or relied on them in weeks when they don’t need them are crucial to the legal victory, officials say. Expect utilities to tighten gates on smart meter data, and investigators will turn more to old tools, such as warrants, targeted tips, and fire or safety code inspections keyed to individual addresses rather than full ZIP codes.

As the network of connected infrastructure expands, so does the risk of “mission creep.” The case of Sacramento is likely to be the reference point for lawmakers as they face off against utilities and police departments across the entire state, which will have to remember that the march toward smarter grids cannot do so at the expense of residents’ privacy.