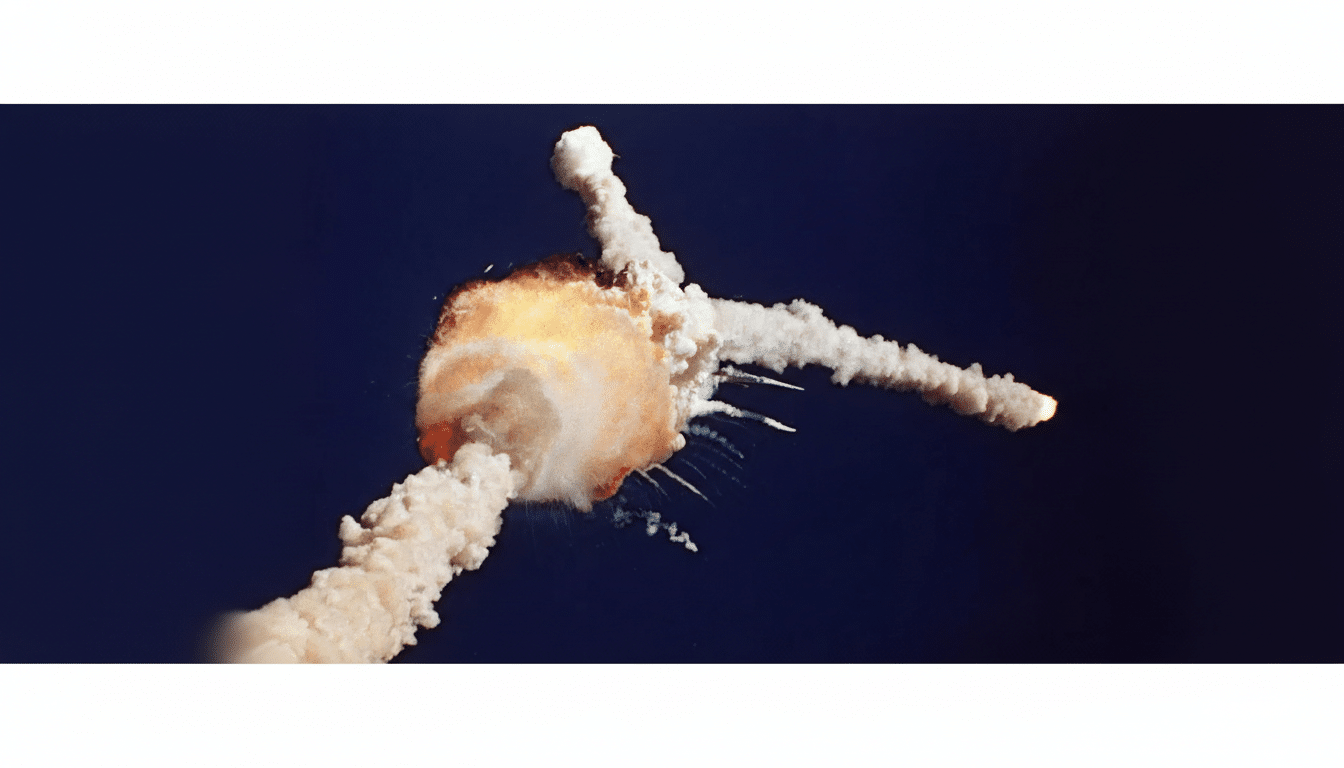

I was seated on a communications console inside NASA Mission Control when the shuttle broke apart. The board in front of me—green lights for healthy telemetry links—blinked to red, one after another, as data vanished mid-climb. In the viewing rooms, Americans watched with us, including classrooms waiting for Christa McAuliffe’s first lessons from orbit; instead, the sky wrote a different, awful script.

My role was mundane until it wasn’t: keep the NASCOM circuits clean, confirm the downlink streams, fight noise on the loops. We worked the S-band paths and tracking network connections that fed Houston the numbers flight controllers live by. Seconds after liftoff, the streams turned ragged, and instinct drove hands to switches before eyes lifted to the screen.

In The Mission Control Room Where Links Went Silent

Mission Control is choreography. Every loop has discipline, every call sign a purpose, yet at crisis scale no one person owns the whole picture. From our seats, data died first: pressures and temperatures that should have marched upward simply stopped, while voice loops tightened into clipped exchanges and long silences. We waited for callouts that never came.

What looked like a single fireball to the public was structural breakup. A solid rocket booster joint failed, exhaust impinged on the external tank, and aerodynamic loads tore the stack apart. The orbiter did not explode in the cinematic sense; it was destroyed by forces far beyond design limits.

Warnings That Went Unheeded Before Challenger

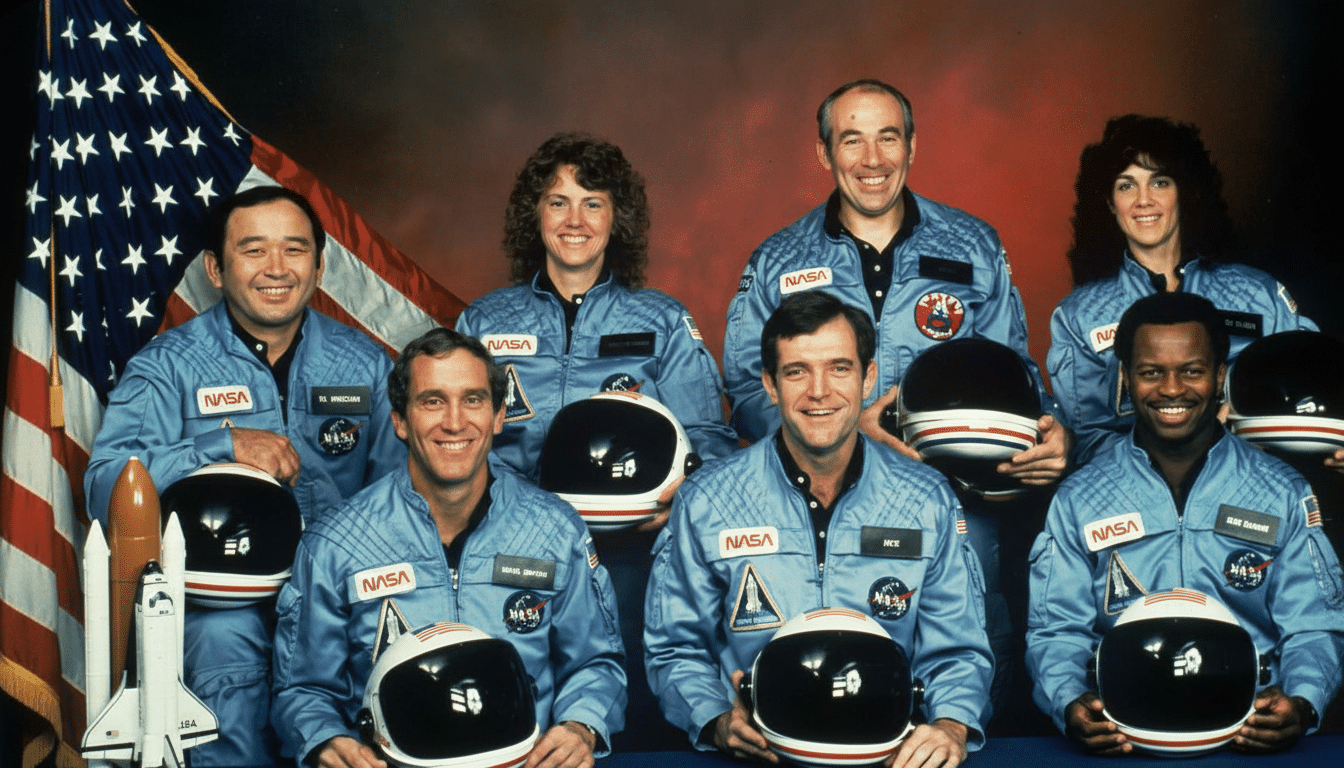

The Rogers Commission would later document what some engineers had already feared: cold-sensitive O-ring seals in the booster field joints had eroded on earlier flights. Morton Thiokol engineer Roger Boisjoly warned of a “catastrophe of the highest order” if those seals were asked to perform outside their tested temperature range. The memo existed; the risk was real; the arguments were lost in the noise of schedule pressure.

Commission member Richard Feynman dipped an O-ring into iced water on live television to show loss of resiliency—an instant, unforgettable demonstration. But the deeper failure was organizational. Decisions filtered upward through layers that softened dissent, a pattern later called normalization of deviance and echoed years afterward by the Columbia Accident Investigation Board.

What The Data Tells Us Now About Challenger

By the end of the shuttle era, 135 missions had flown; two were lost with their crews, a roughly 1.5% catastrophic failure rate. That is an extraordinary achievement by the standards of experimental flight—and an unacceptably high number by the standards of routine transportation. Spaceflight lived between those two truths, and culture too often chose the latter before engineering had earned it.

Telemetry reconstructed the sequence: a right booster leak, flame impingement near the intertank, structural compromise of the external tank, and rapid disassembly under aerodynamic load. Those traces became case studies for generations of controllers—how to read weak signals in real time and when to trust a gut alarm that says something fundamental has changed.

The Commission’s technical fixes were clear: redesigned booster joints with capture features and heaters, tougher flight readiness reviews, and an independent line for safety. Equally vital were the cultural repairs—empowering engineers to stop a countdown, rewarding bad-news candor, and treating uncertainty as a hard constraint, not a hurdle to finesse.

Why The View From Mission Control Still Matters

From the console, the lesson is personal: if your link goes red, you own it; if your data says no-go, you say it plainly on the loop. Space does not forgive euphemism. The organizations that thrive are the ones that make it easy to voice doubt and hard to bury it.

Budgets shape behavior. NASA’s share of federal spending has hovered near 0.5%, enough to do world-class science but not always enough to refresh every aging system. In our control rooms, redundancy sometimes meant coaxing life from legacy circuits built decades earlier—a testament to ingenuity, and a reminder that ingenuity is not a substitute for investment.

Human spaceflight now spans agencies and industry. NASA’s Commercial Crew program restored domestic rides to orbit, Soyuz remains a proven workhorse, and companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin are pushing toward deeper space. The engineering changes after Challenger—and Columbia—flow through all of them, in joint designs, hazard analyses, and flight test doctrines.

I still hear the quiet of that room when the numbers stopped. The only enduring tribute worthy of the crew we lost is discipline: evidence over optimism, dissent over deference, and the courage to wave off when conditions drift outside the box. Exploration will always carry risk; our duty is to refuse the preventable kind.