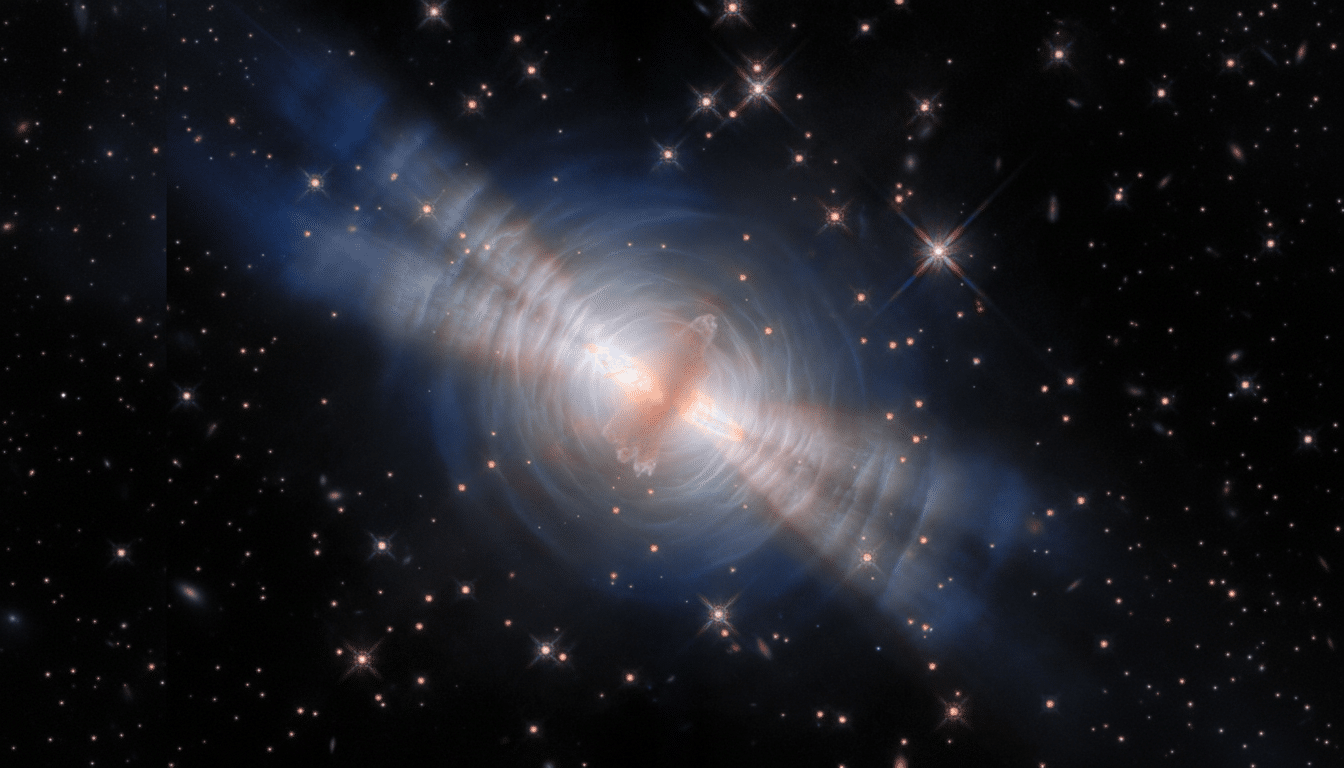

The Hubble Space Telescope has delivered a piercing new look at the Egg Nebula, capturing the faint, last gleams of a Sun-like star as it enters its terminal phase. The object, cataloged as CRL 2688 and located roughly 1,000 light-years away in Cygnus, is swaddled in dust so dense that only narrow shafts of starlight escape through polar openings. The result is a striking, mirror-bright spectacle that astronomers say records a crucial, fleeting stage of stellar death.

A Rare Glimpse Of A Brief Stellar Phase

The Egg Nebula is a prototype of a pre-planetary nebula, the short transitional interval between a bloated red giant and a fully formed planetary nebula. In this window—lasting only hundreds to a few thousand years, a sliver far below 0.001% of a Sun-like star’s lifetime—the central star is hotting up but has not yet ionized its surroundings. According to NASA and the European Space Agency, the glow we see is predominantly starlight scattered off soot-rich dust grains, not gas excited by ultraviolet radiation.

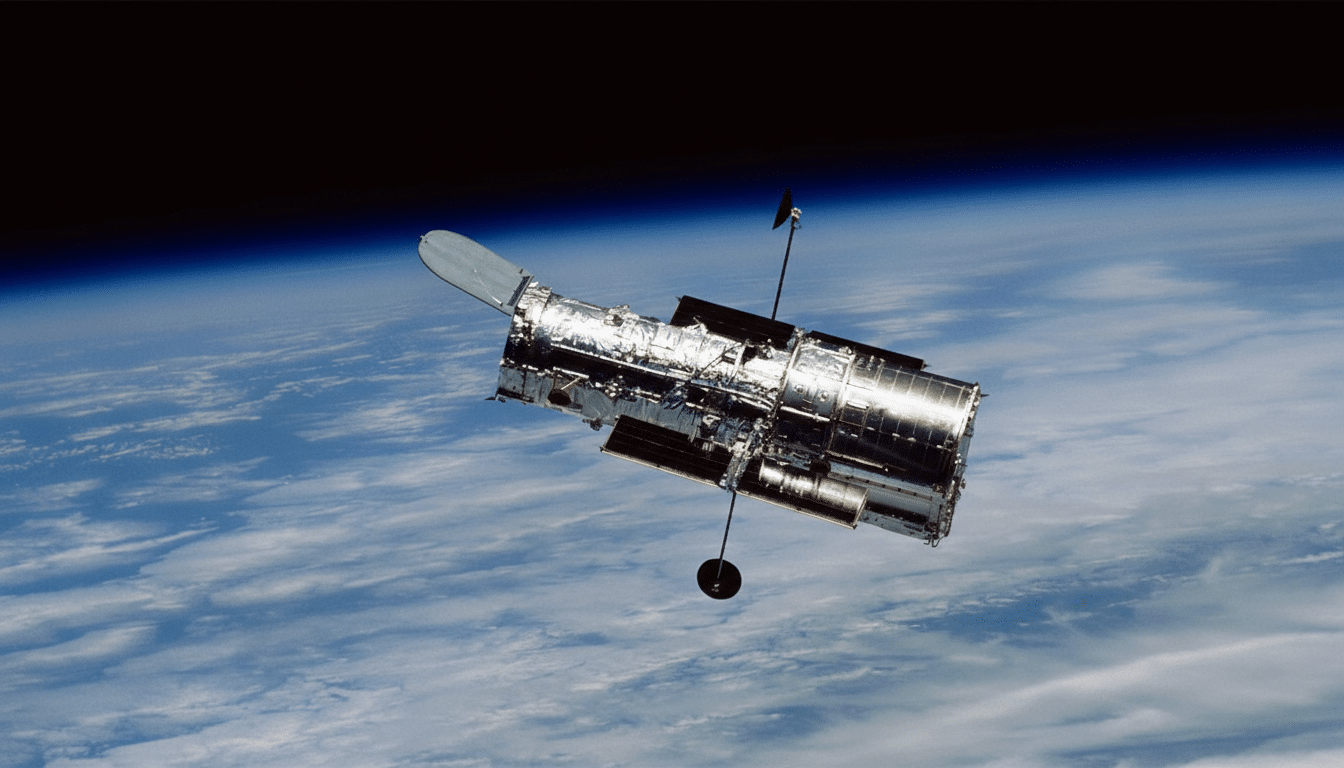

Hubble’s latest portrait stitches together multi-epoch observations to reveal how the scene is changing in real time. That’s unusual in astrophysics: structures here shift over mere decades, allowing researchers to trace the tempo of mass loss as the star sheds its outer layers and approaches white dwarfhood.

Inside The Egg Nebula: Structure, Jets, and Dust Dynamics

At the nebula’s heart is a dying star cloaked by a thick, carbon-rich disk ejected only a few hundred years ago, based on expansion measurements from repeated Hubble imaging. Light leaks out near the poles, projecting crisp searchlight beams that illuminate lobes hollowed by fast-flowing outflows. Those jets likely reach speeds of more than 100 kilometers per second, boring through an older, slower wind moving at several tens of kilometers per second—classic signatures of late-stage stellar evolution.

Surrounding the lobes are evenly spaced arcs, like tree rings, that chronicle episodic puffs from the star’s envelope. Their regularity rules out a single cataclysmic blast and instead points to recurrent mass-loss bursts, potentially tied to pulsations or magnetic cycles during the asymptotic giant branch phase. By comparing the spacing of the arcs with their measured drift, astronomers can estimate the cadence of these outbursts—on the order of centuries.

Clues To A Hidden Companion Shaping The Egg Nebula

The Egg’s bilateral symmetry and sharply collimated jets hint that the star may not be acting alone. Increasingly, studies of pre-planetary and planetary nebulae suggest that companion stars—or even massive planets—help shape the gas through gravitational torques, accretion disks, and precessing jets. The tidy geometry in CRL 2688 aligns with this picture, where an unseen partner inside the dust disk could be steering the flow, carving canals through which the light now escapes.

Image credits list Bruce Balick of the University of Washington among the astronomers who have long scrutinized the Egg Nebula with Hubble. Their work, alongside teams supported by the Space Telescope Science Institute, has turned this object into a benchmark for testing how binary dynamics sculpt dying stars’ envelopes.

Why Hubble’s Time-Lapse Matters For Stellar Endgames

By revisiting the Egg Nebula over decades, Hubble enables “expansion parallax” measurements—tracking the outward motion of structures to refine the object’s distance and age. Subtle motion of dust clumps, shifting jet tips, and brightening or dimming filaments offer a laboratory for calibrating models of mass loss, momentum injection, and dust formation. These empirical constraints are vital: the amounts and speeds of material expelled now will determine the shape, brightness, and chemistry of the planetary nebula that follows.

NASA and ESA note that the star’s ultraviolet output is still too low to energize the gas, which is why CRL 2688 shines by reflection rather than emission. As the core heats past tens of thousands of kelvin in the coming millennia, the gas will ionize, and the object will transition into a luminous planetary nebula—before fading as the remnant contracts into an Earth-sized white dwarf of roughly 0.6 solar masses.

A Preview Of The Sun’s Distant Future After The Red Giant

The Egg Nebula’s choreography offers a sobering preview of what awaits our own Sun. Billions of years from now, the Sun will expand into a red giant, likely engulfing the inner planets and expelling vast shells of gas and dust. That debris will be shaped by winds and possibly by unseen companions, before the Sun’s hot core lights up the cloud as a planetary nebula. Eventually, all that remains will be a cooling white dwarf amid a fossil shell—an echo of the spectacle Hubble is currently recording in CRL 2688.

For now, the Egg Nebula stands as one of the nearest and youngest examples of a star’s final exhalations. With each return visit, Hubble sharpens the timeline of stellar death, turning an ephemeral moment—measured in centuries—into a richly detailed narrative written in beams, arcs, and dust.