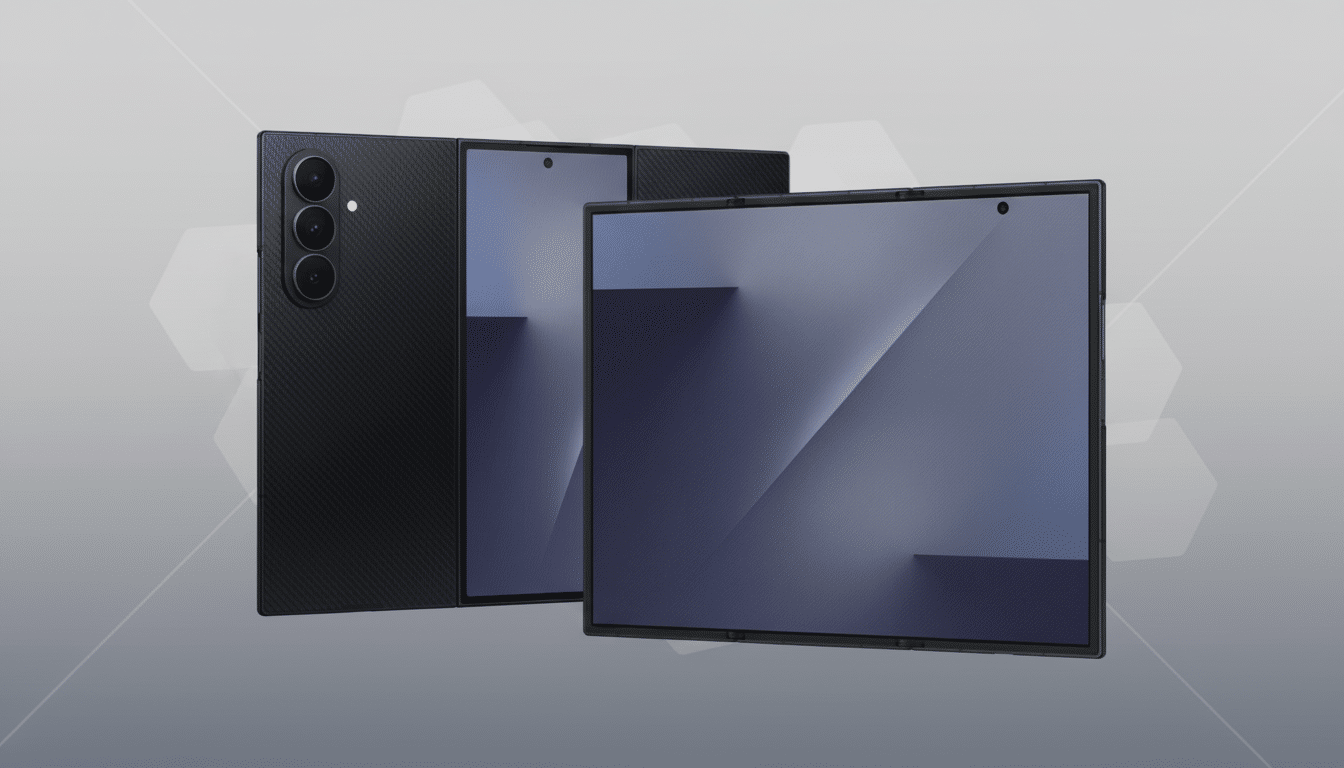

Samsung’s Galaxy Z TriFold sold for around $2,400 in Korea at launch, although industry reports indicate that the company still sells each device at a loss. The strange economics of the device are a reminder of just how difficult and prohibitively expensive triple-folding hardware is, even for a company with Samsung’s size and supply chain reach.

Why a $2,400 Phone Still Loses Money for Samsung

Korean publication The Bell claims the Galaxy Z TriFold actually costs more to make than it sells for, suggesting that Samsung would be making negative margins on the device. It’s not difficult to imagine the outcome there: a multi-fold-radius tri-fold OLED with two hinge systems, layered special ultra-thin glass stacks, stronger chassis components, and segmented batteries is inherently more complicated than a typical foldable. Yields on new displays in early generations are low, and yield pain goes directly to adding to the bill of materials (BOM) and manufacturing overhead.

- Why a $2,400 Phone Still Loses Money for Samsung

- Small Batches Kill Economies of Scale in TriFold Production

- Regional Pricing Suggests Cross-Subsidies

- Component Inflation Is Indeed a Headwind

- Snapdragon Mix Muddies the Water for Galaxy S26 Pricing

- The Strategic Argument: Why Attrition Is Rational

- What to Watch Next for Samsung’s TriFold Economics

There is a high price beyond the screen. Extra digitizers, layered wiring harnesses for moving parts, additional camera periscopes to hit the thickness targets, and proprietary thermal solutions are all part of that. Assembly time is longer; quality control is more difficult. In that sort of design, every tenth of a millimeter is expensive.

Small Batches Kill Economies of Scale in TriFold Production

The TriFold is only going to be made in a limited number by Samsung, for several markets. Low volume = weak component pricing, little amortization of R&D/tooling/test fixtures, and more warranty reserve per unit. Display Supply Chain Consultants has said multiple times that the cost of foldable panels does not meaningfully drop off until yields plateau and volumes grow, and a first-wave tri-fold ships before either happens in full.

Analysts at Omdia and Counterpoint Research have also pointed out that a fixed-cost challenge has emerged with new form factors: if you make a small run, each phone carries an outsize share of engineering, validation, software optimization, and service setup costs. That math is brutal — even at ultra-premium price points.

Regional Pricing Suggests Cross-Subsidies

The Korean price of the TriFold still hovers at just over $2,440 when converted to U.S. dollars, but you can buy it for about $3,260 in the UAE. Variations can arise from taxes, distribution, and currency fluctuations, but the spread also implies that Samsung may be leveling out margins on a global basis. In reality, that might mean tapping higher-cost regions to counteract strategic pricing at home, where brand halo and early adopter exposure come with added value.

Component Inflation Is Indeed a Headwind

Industry trackers say input prices are increasing. TrendForce has highlighted continued upward DRAM/NAND pricing pressure from AI server demand and limited supplies, which is cascading to high-end phones stacked with the most memory. DSCC wrote that a cost premium for such advanced foldable OLED stacks continues to exist, especially when it comes to new substrates and cover lens treatments. At the same time, image sensor manufacturers have been driving larger-format, higher-resolution modules that carry a premium.

When you add pricey parts with low yields, even a $2,400 sticker may not make the cut. Shipping a tri-fold at scale is a manufacturing marathon, not a sprint, and the early laps are expensive.

Snapdragon Mix Muddies the Water for Galaxy S26 Pricing

The Bell also claims that Samsung is struggling with pricing for its Galaxy S26 series, citing expensive memory, OLEDs, and camera modules. One major variable is the chipset mix: while Samsung switches between Qualcomm Snapdragon and in-house Exynos chipsets for its different markets, Snapdragon is said to account for at least 75% of this cycle’s crop. This also means that if retail prices can’t sync, Qualcomm’s flagship silicon tends to carry a premium above Exynos and margins come under pressure.

That calculus goes back to the TriFold. If the company’s mainstream flagships come under cost pressure, then it has even less wiggle room to subsidize experimental hardware. But halo devices frequently deserve separate math, particularly when they put a shine on core competencies from Samsung Display and dictate terms for future categories.

The Strategic Argument: Why Attrition Is Rational

It’s possible to ship a limited-run TriFold product at negative margin and still be rational. The device claims multi-fold UX leadership, sows developer interest in humongous Android interfaces, and stress-tests manufacturing processes that may trickle down to cheaper models eventually. And it reinforces the ecosystem around Samsung’s foldable brand and helps keep competitors from owning the narrative about multi-fold designs.

Internally, part of the value accrues to Samsung Display, which can claim its own benefit from growing the foldable panel frontier even if that means taking a temporary hit on the mobile division’s P&L. Or, in other words, the group-level payoff might exceed what the per-unit math suggests.

What to Watch Next for Samsung’s TriFold Economics

Three signals by which we’ll measure the TriFold’s success in making it from loss leader to product line:

- Display yields improve quarter over quarter.

- A second-generation design that combines hinges and reduces thickness.

- Broader market exposure rather than just several regions.

Watch for memory pricing from TrendForce, panel cost roadmaps from DSCC, and any clues about Samsung’s Snapdragon–Exynos split in next year’s flagships. If those inputs all break toward Samsung, the $2,400 sticker might someday look like an investment rather than a wager.