Florida is advancing a highway segment that would let electric vehicles charge as they drive, the first such system to emerge in the U.S. and one that could upend transportation if officials are able to track its success. The Central Florida Expressway Authority will get started on the work in 2026 to construct the 3/4-mile inductive charging lane within State Road 516, and open the route up to motorists by 2029.

How the Wireless EV Charging Highway Works

Coils under the road will generate a magnetic field. Vehicles outfitted with receiver coils would then pick up that energy and transform it into electricity while driving, a process called dynamic wireless power transfer. Instead of charging that takes place at the curb or on a pad, power is transferred constantly over a section of pavement to avoid having to sit at chargers and potentially meaning smaller onboard batteries down the road.

It is no longer theoretical. Earlier this month Purdue University and the Indiana Department of Transportation tested a system that transferred 190 kilowatts to a semi-truck at 65 mph, power levels that would suffice for even heavy-duty tasks and are well more than what it would take to charge a typical passenger car traveling the highway. The architecture, Purdue researchers declare, is scalable between Class 8 trucks and compact EVs — given vehicles are outfitted with appropriate receivers.

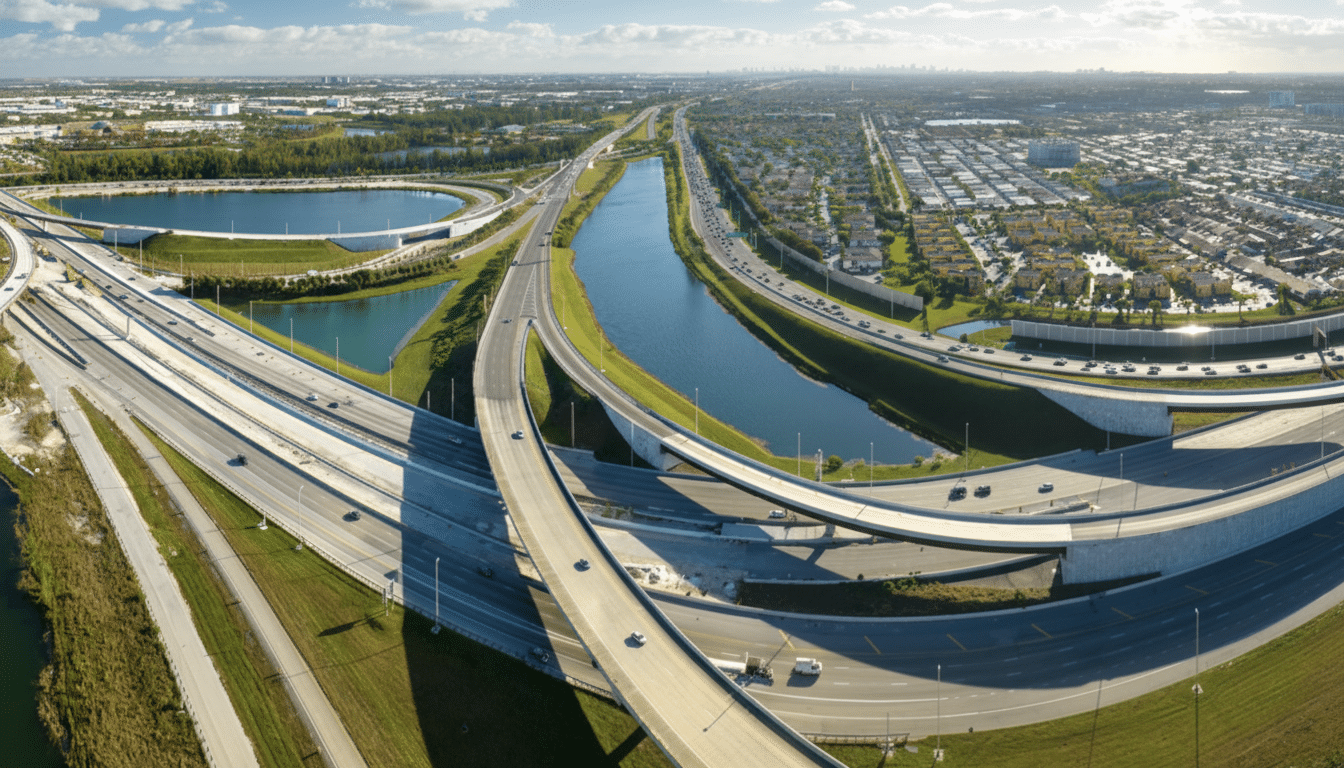

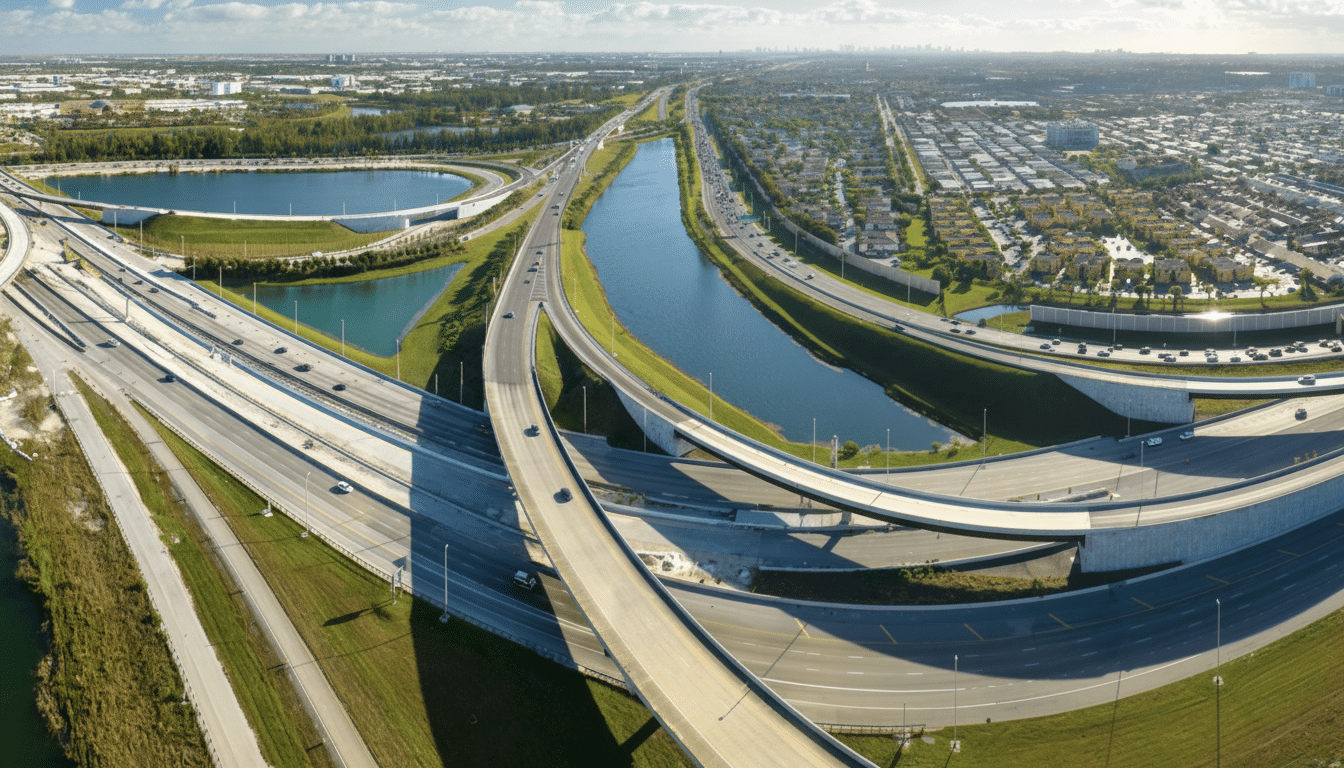

Scope and Timeline in the Central Florida Region

The Florida test operates on the 4.4-mi (7-km) SR 516 Lake/Orange Expressway, which CFX is currently constructing in three sections. The wireless charging lane will cover a 3/4-mile stretch in part of the first section. The road will open to all vehicles after testing is complete, but initially only instrumented “specially equipped” cars will receive power as CFX and its technology suppliers prove out the system’s ability to perform safely and interoperably.

It’s not clear yet whether the pilot would favor trucks or passenger vehicles. Because trucks drive predictable routes and can provide clear total-cost-of-ownership data, many real-world tests have begun with commercial fleets. In France, a live section of highway is wirelessly charging trucks in partnership with Electreon, and Michigan’s Department of Transportation installed a quarter-mile test roadway open to the public in Detroit with the same company.

Why Florida Is Experimenting With Dynamic Charging

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, Florida is one of the fastest-growing EV markets in the country based on total vehicle registrations, second only behind California. But the rush to adopt is meeting some old obstacles: range anxiety on highways, peak-time traffic at fast chargers and grid limitations at popular locations. A highway that overcomes the bottleneck is one where charge is delivered as you drive, directly addressing these bottlenecks by smoothing out energy consumption and by reducing wear on stationary infrastructure.

Dynamic charging also happens to complement future autonomy. Vehicles that can drive themselves to a charge zone don’t need a driver to plug them in, and fleets — whether robotaxis or delivery vans or buses — could benefit from more time on the road. It is no accident that the auto and mobility sectors are looking at wireless charging more extensively; Tesla, for example, has openly discussed potential wireless pathways to power robotaxis in the future—demonstrating the operational benefits of cable-free energy transfer.

Technical and Policy Hurdles Facing Dynamic Charging

Yet despite the momentum, there are formidable barriers. Working coils into pavements requires a new construction technique, waterproofing challenges and planning for periodic repaving. The extreme heat and rain of Florida have added additional guidelines for durability. Utility operators will have to plan grid upgrades and smart controls to handle high draws, especially if more than one vehicle parks in the charging lane at once.

Cost is another swing factor. Industry estimates put the cost of dynamic charging infrastructure in the low millions of dollars per lane-mile, depending on power level and site condition. Policymakers will want to see clear metrics: cost per delivered kilowatt-hour, efficiency over time, maintenance requirements and pavement performance. From the standards perspective, SAE’s J2954 has provided a stepping stone toward light-duty wireless charging, and its cousin, J2954/2, aims to standardize a dynamic system—interoperability in this context is important to minimize vendor lock-in.

Finally, the project would have to reinforce—rather than replace—stationary fast charging. National-level programs like Australia’s National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure project concentrate on DC fast-charging stations on highways. If successful, Florida’s dynamic pilot would layer a new capability on top of that network, clipping peak loads and stretching usable range without compelling more frequent stops.

What Success Will Look Like for Florida’s Pilot

CFX and its partners will be examining whether vehicles do not drop their charge while cruising at highway speeds, whether energy transfer is optimal even during extreme rain events or high temperatures, and how pavement holds up to wear and tear without emitting dangerous substances through repairs that could cost more than standard asphalt.

If trucks are in the mix, freight operators will weigh whether dynamic charging shrinks battery requirements, boosts payload or enhances route economics.

If Florida’s 3/4-mile stretch proves out the model — and is made part of projects in Indiana, Michigan and Europe — it could open the door for longer segments on freight corridors and strategically targeted urban arterials. Now that the state has reliable data on performance, safety and cost, it could help to propel dynamic charging from pilot to playbook, transforming a short stretch of SR 516 into a map for next-generation EV infrastructure.