The United States has taken steps to clamp down on foreign-manufactured unmanned aircraft systems as the Federal Communications Commission expands its Covered List to include drones and elements of drone technology from beyond its borders. The change lands most heavily on DJI, the leading player in consumer and prosumer drones, and represents a further tightening of coordination between telecom oversight and national security policy.

Foreign-made drones are assumed to be covered and, therefore, not eligible for new equipment authorizations unless national security agencies grant a waiver under the new framework. In practical terms, that restricts the importation of new models and many replacement parts, but it leaves certified devices already in existence and on store shelves for now.

What the FCC Changed in Its Expanded Covered List

The FCC’s Covered List, which was meant to stop communications equipment that is considered dangerous to United States networks, now explicitly includes drones manufactured abroad. Pursuant to the Secure Equipment Act, the Commission may not authorize new radiofrequency equipment from listed entities or categories, and unauthorized products can’t be legally sold or imported.

Importantly, the rules are not retroactive. As before: Pilots can continue to operate their existing planes, and retailers can sell off remaining stock. Yet foreign brands will struggle to test new models or modules, and distributors probably will find spare parts caught up at the border.

What Consumers and Pilots Will See Under New Rules

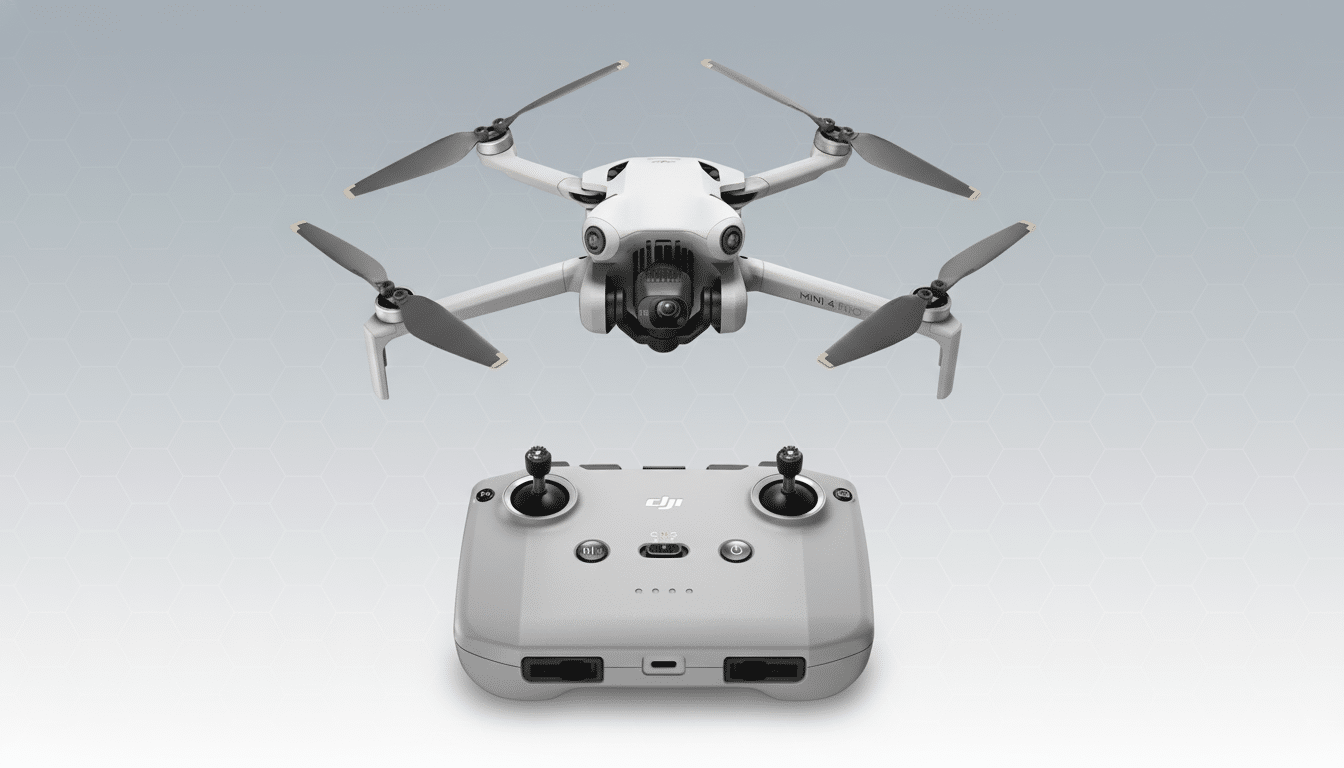

Hobbyists and Part 107 pilots can still fly their drones in normal circumstances. The immediate pinch will be for maintenance — batteries, camera gimbals, flight controllers and other RF-linked components may become more difficult to source, and many manufacturers won’t take U.S. units back for repair at their factories overseas. Independent repair shops could confront a parts shortage if inventories run low.

The possible amount of disruption is vast. The FAA has logged more than 870,000 drones on its registry and over 300,000 certified remote pilots, with DJI aircraft making up a large percentage of both the recreational and commercial markets. Emergency services and inspection companies that standardized on DJI may need contingency plans for keeping the aircraft working through the parts squeeze.

The Prime Target Is DJI, Despite Not Being Named

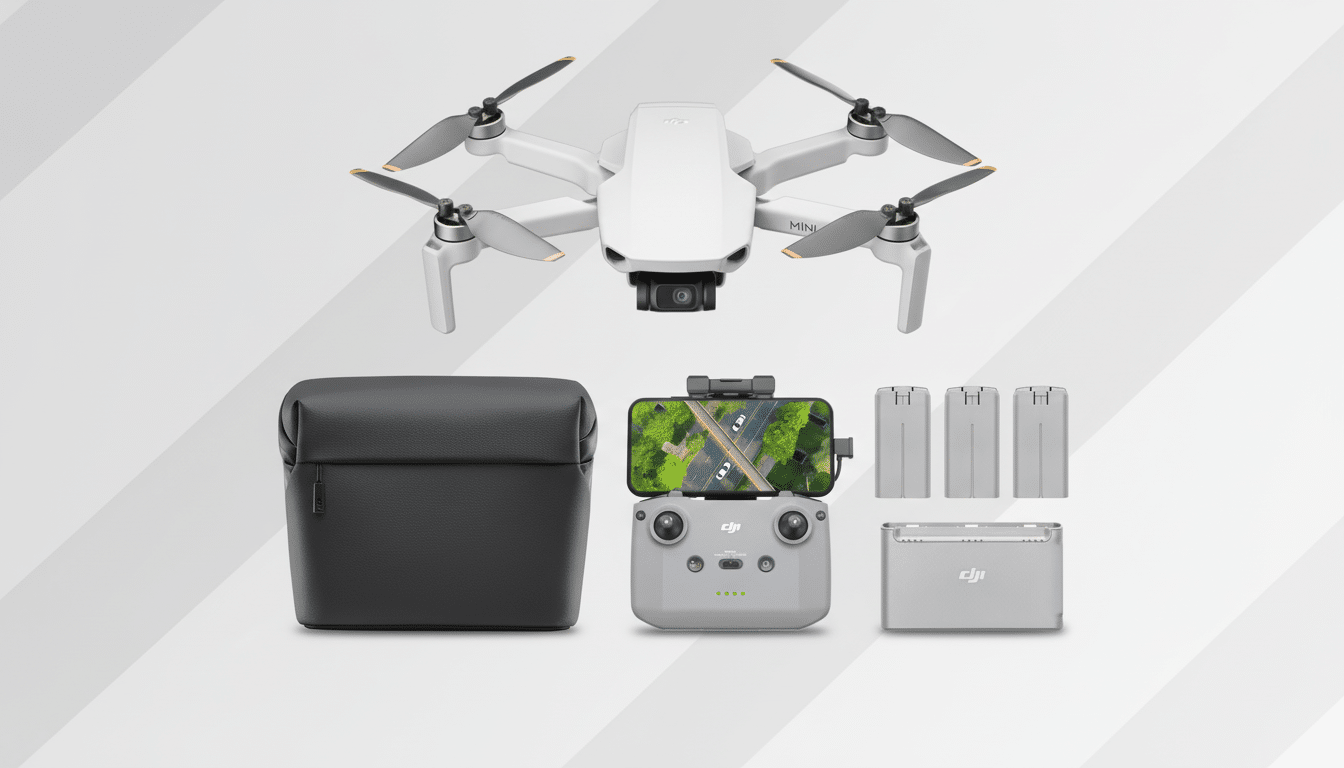

Analysts say DJI has about 70% share in the global consumer drone market and is well represented in U.S. public safety and infrastructure inspection. The new restrictions add to existing headwinds: U.S. Customs and Border Protection has stopped some DJI shipments under the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, which the company has contested. Products like the Neo 2 are still not available domestically, and those same restrictions can widen as supply lines prove vulnerable.

Autel, another Chinese manufacturer, is also in the crosshairs. The FCC action doesn’t mention DJI by name, but it erects a boundary that would largely prevent foreign-made UAS from entering the U.S. market — unless carve-outs are offered to national security agencies. DJI has reacted with disappointment and queried the evidence behind the decision, public statements carried by national media said.

Security and Policy Backdrop Driving the FCC Move

Washington has been particularly wary of foreign drones, citing fears that the telemetry or imagery or flight logs from such devices could be retrieved by adversarial governments. Blue UAS, a program for the Defense Department, has approved a vetted list of platforms for use by the federal government, and an arm of Congress known as the Government Accountability Office cited risks related to data flows through software supply chains. Recent cybersecurity advisories by CISA have advised agencies to assess UAS data paths and the origin of firmware.

The federal stance has influenced states and cities. Florida, for instance, ordered agencies to phase out certain foreign-made drones, requiring law enforcement and public safety departments to ground fleets and seek replacements. The FCC’s action brings the consumer and commercial markets one step closer to the purchasing requirements that are already standard in government.

Winners, Losers, and Workarounds in the Drone Market

Manufacturers in the United States and its allies could capitalize. Skydio and others, including Teal Drones, Inspired Flight, along with Parrot’s ANAFI USA and Sony’s Airpeak, are well-positioned to take a level of demand from public safety and industrial inspection. The challenge: scale — matching DJI’s breadth of models, accessory ecosystems, and price points will take time, and buyers should expect squeezed inventories and higher sticker prices in the short term.

Enterprise buyers could hasten multi-vendor strategies — keeping legacy DJI aircraft in the air while adding Blue UAS options for sensitive missions. Data residency, on-device encryption and offline workflows are going to be much more common in RFPs than they were before, as organizations re-baseline security requirements.

Pilots: What You Can Do Now to Prepare for Changes

If you fly a foreign-made drone, plan to stock consumables like props and batteries; verify compliance with Remote ID regulations — which have yet to be hammered out on the Texas Gulf Coast, let alone in Beijing or Seoul — and map domestic repair sources in advance.

For agencies and businesses, audit fleets, prioritize mission-critical aircraft for parts reserves, and re-evaluate standard operating procedures to segregate low-risk legacy use cases from sensitive, high-risk operations that justify U.S.-approved platforms.

The bottom line: This isn’t an instant grounding, but it’s a dramatic resetting of the market. With foreign-made drones at least now all but frozen out of new FCC approvals, the U.S. drone market will soon tilt to domestic and allied providers — or at least faster for government buyers than over a longer period for everyone else.