ATM jackpotting is no longer a conference parlor trick. In a new bulletin, the FBI warns that coordinated attacks on cash machines have accelerated, with more than 700 incidents in the past year alone and at least $20 million in cash losses. The agency says crews are blending physical access with malware to force dispensers to spew bills on command, often in minutes and without touching a single customer account.

How ATM Jackpotting Attacks Work, From Access to Cash-Out

Jackpotting typically unfolds in two acts. First, criminals gain hands-on access to the machine—popping the top panel with generic keys that are too widely available, drilling access points, or posing as field technicians to reach the hard drive or USB ports. Second, they trigger a “cash-out” using either internal malware or a so‑called black box that talks directly to the dispenser unit.

- How ATM Jackpotting Attacks Work, From Access to Cash-Out

- Ploutus Malware and Weaknesses in the ATM XFS Layer

- Who Is Being Targeted by Coordinated ATM Jackpotting

- Why ATM Jackpotting Is Growing and Defenses Lag Behind

- What Banks and ATM Operators Can Do to Reduce Risk

- The Bottom Line on Rising ATM Jackpotting and Losses

These jobs are organized. Planners and coders supply tools, while local “mule” teams execute the withdrawals and vanish. Because the attack targets the terminal itself, banks may not see fraud alerts tied to cards, and the loss often isn’t evident until someone reconciles the cassette counts.

Ploutus Malware and Weaknesses in the ATM XFS Layer

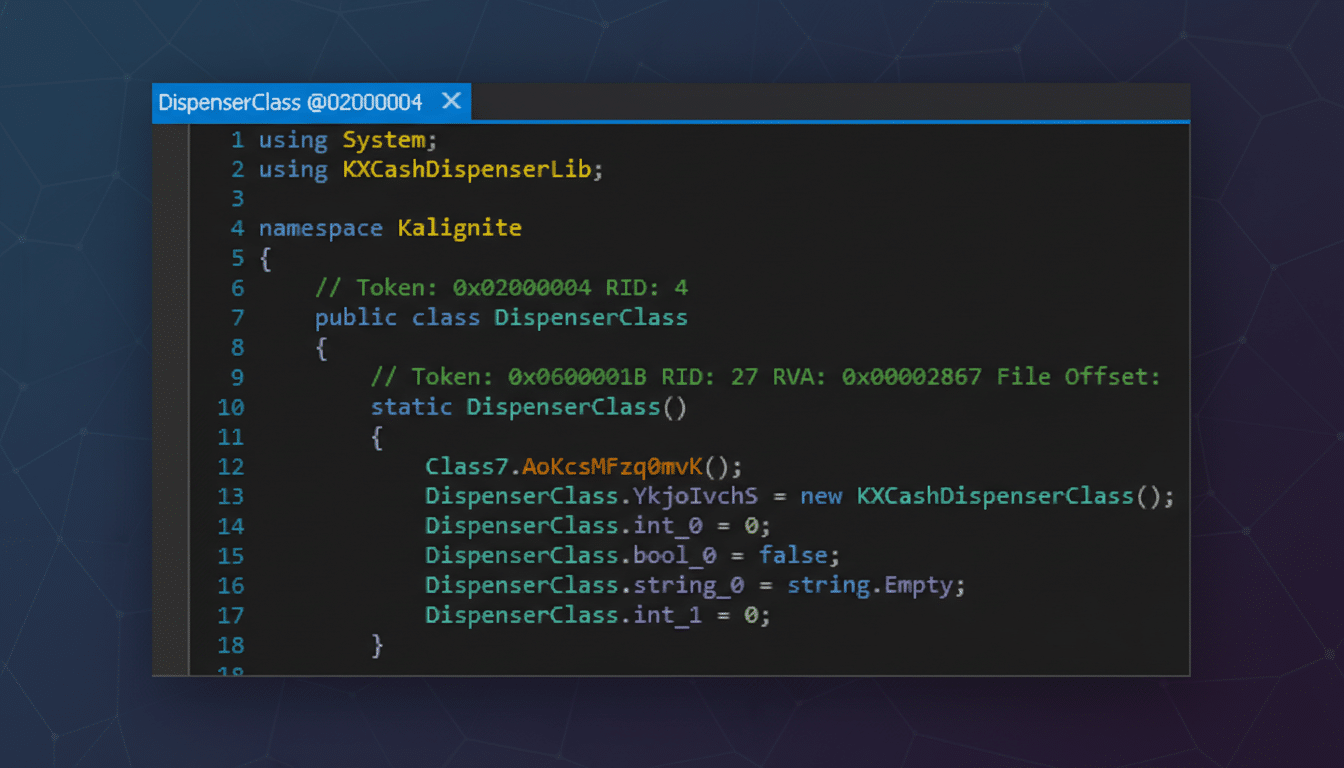

The FBI highlights Ploutus, a mature family of ATM malware that abuses the Windows-based software stack many machines still rely on. By hooking into the eXtensions for Financial Services (XFS) layer—the middleware ATMs use to orchestrate the keypad, card reader, sensors, and dispenser—Ploutus can issue legitimate‑looking commands that unlock the vault of cash without a corresponding ledger entry.

That makes detection hard. The malware targets the ATM, not a customer profile, so traditional anti-fraud systems may stay quiet during a rapid cash‑out. Security researchers and payments networks have warned for years that weak or misconfigured XFS implementations can be coerced into bypassing normal business logic, particularly when devices run outdated operating systems or allow unrestricted local ports.

Who Is Being Targeted by Coordinated ATM Jackpotting

Attackers go where defenses are thinnest. Independent ATM deployers in retail locations, machines with inconsistent maintenance, and models with known physical bypasses are frequent targets. Large banks are not immune either; criminals have hit multiple manufacturers and dispenser types, from lobby units to drive‑ups, wherever they can find predictable locks, default configurations, or lax technician verification.

The U.S. Secret Service has previously cautioned operators about jackpotting on specific legacy models, and the European Association for Secure Transactions has documented waves of logical and black‑box attacks across the region. Law enforcement says many crews are cross‑border, moving quickly to exploit shared parts, cloned service keys, and repeatable playbooks.

Why ATM Jackpotting Is Growing and Defenses Lag Behind

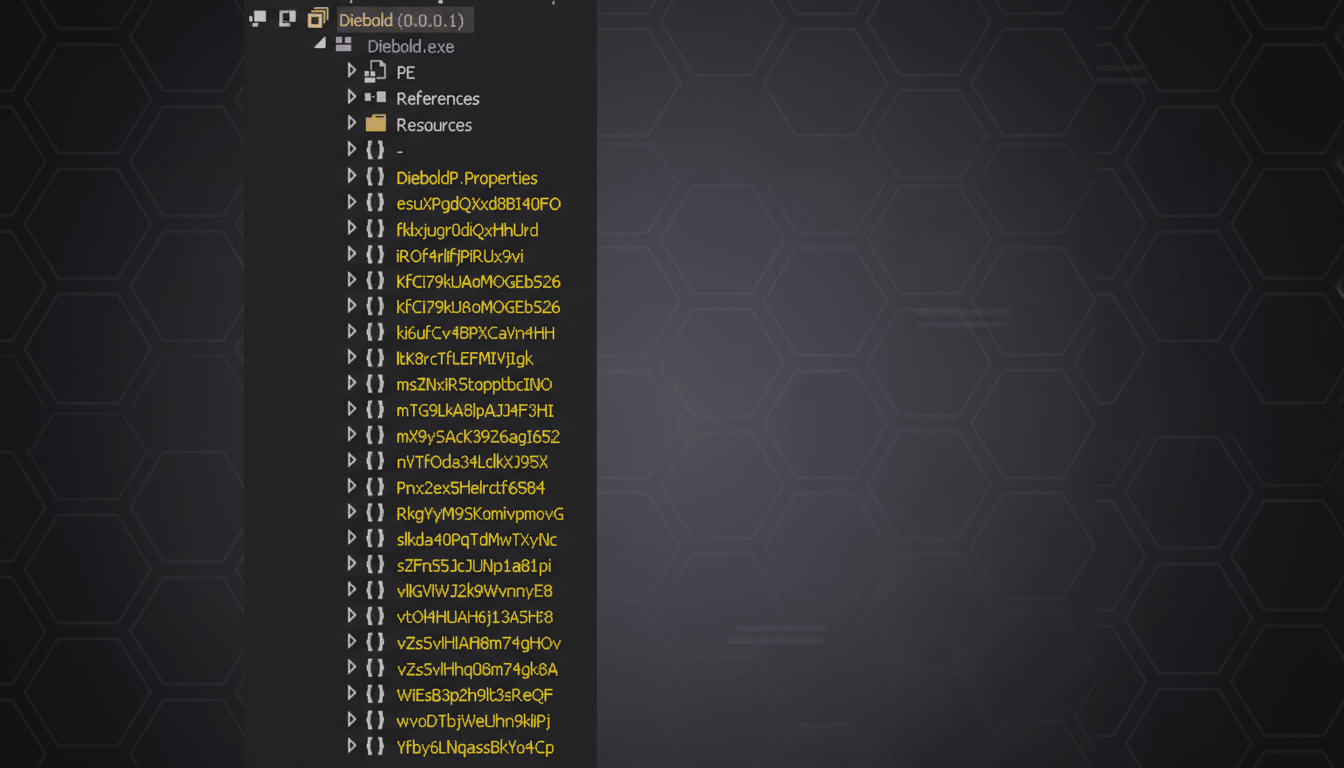

Several trends are converging. First, a robust criminal supply chain now offers turnkey jackpotting kits, from universal lock sets to preloaded drives and step‑by‑step scripts. Second, too many terminals still run end‑of‑support software or ship with permissive XFS settings that make lateral control simple once someone is inside the cabinet.

Third, operational gaps—like single‑person maintenance visits, loosely tracked technician credentials, or unmonitored after‑hours access—give attackers the time window they need. Finally, defenders have historically focused more on card fraud than on the ATM as an endpoint, leaving blind spots in logging, tamper detection, and real‑time cash‑out analytics.

What Banks and ATM Operators Can Do to Reduce Risk

Hardening must start with physical control. Replace generic master keys, rotate locks, and add cabinet and safe sensors tied to alarms. Disable unused ports; add BIOS and USB locks; enforce secure boot and signed firmware. On the software side, move to fully supported operating systems, patch XFS components, and deploy application whitelisting so only authorized binaries can run.

Instrument the dispenser. Telemetry that tracks dispense counts, cassette status, door events, and service‑mode transitions can spotlight a live jackpotting attempt. Pair that with velocity rules, geofencing, and unusual maintenance‑window alerts to trigger rapid response. Reduce cash exposure by right‑sizing loads on vulnerable routes and staggering replenishment schedules.

Tighten people and process controls. Use dual control for service visits, verify technician identities against work orders, and log every cabinet open/close with video. Regularly red‑team ATMs to validate that locks, alarms, and software controls hold up under hands‑on attack. Share indicators with industry groups such as FS‑ISAC and ATMIA, and coordinate with the FBI, the Secret Service, and CISA for rapid takedown of tool suppliers and mule networks.

The Bottom Line on Rising ATM Jackpotting and Losses

Jackpotting exploits a simple reality: if criminals can control the dispenser, they control the cash. The FBI’s alert underscores that this is an at‑scale problem, not a curiosity. Treat ATMs as high‑value endpoints, not appliances. The institutions that standardize unique locks, modernize software, monitor dispenser behavior, and lock down maintenance will be the ones that turn a fast cash‑out into a fast fail for attackers.