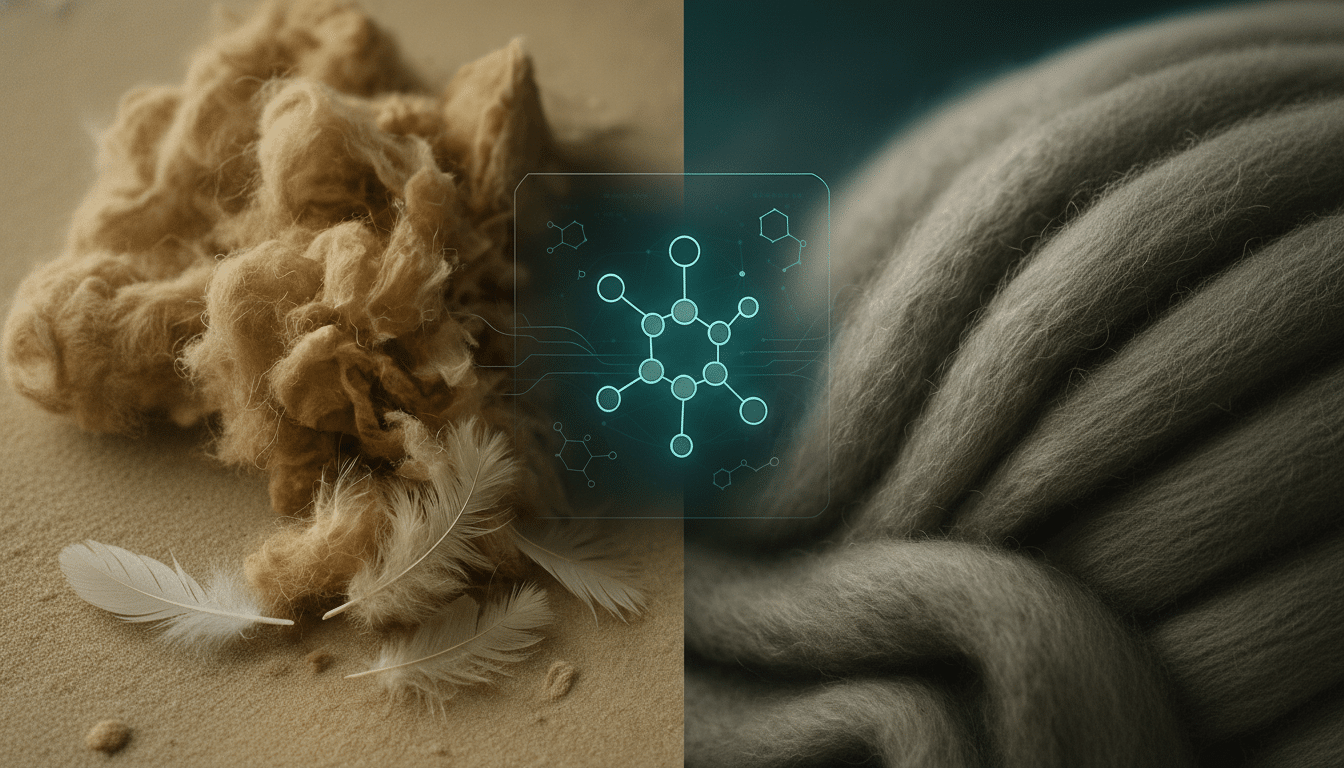

It is cashmere’s meteoric rise that has run up against hard limits on supply, but one start-up thinks it can separate the luxury feel from the goats that provide it. Everbloom, in contrast, claims its new material science platform can turn keratin-rich waste — such as chicken feathers — into fibers engineered to replicate cashmere, and the company argues that it can offer brands a drop-in alternative at a lower cost and standard impact.

How the Fiber Engine Works to Replicate Cashmere

At the core is Braid AI, Everbloom’s formulation engine that tweaks chemistry and processing parameters to hit targeted handfeel and performance numbers. Rather than inventing fancy machines, the company processes keratin waste into pellets that can be fed through a standard plastic-extrusion machine and then conventional spinning equipment similar to what is used for polyester.

Everbloom claims that because of the process limitation to extrusion and spin, capital costs are low while scalability is high. The gamble is straightforward: Dozens of the world’s largest mills can easily adopt a fiber that runs on the same equipment spewing out most of the planet’s synthetics right now — with no costly retooling. That same kind of equipment is used in about 80 percent of the textile market, according to the company.

From Poultry Waste to Premium Handfeel in Textiles

Feathers might seem an unusual feedstock, but they are nearly pure keratin — the structural protein also found in wool and cashmere and human hair. The Food and Agriculture Organization has calculated that billions of pounds of feathers are produced globally annually through poultry processing, a lot of which ends up as low-value animal feed or waste in landfills.

Everbloom’s procedure liquefies and conditions keratin waste, then adds in proprietary biodegradable supplements. The mix is extruded into pellets and spun into continuous fibers, with Braid AI adjusting inputs to hit targets such as fineness, crimp and tensile properties. One goal is to mimic the softness of cashmere; with another push of a button, that same platform can produce polyester for applications in which durability and price take precedence over plushness.

Cashmere Needs a Rethink — and Here’s Why

Traditional cashmere is from the fine undercoat of some goat breeds, and the supply constraint is glaring: A single goat gives up only about 4 to 6 ounces of usable fiber a year. As demand has skyrocketed, the numbers of animal herds have swelled in some parts of Mongolia and Inner Mongolia. Conservation groups and researchers have tied that expansion to degradation of grasslands and increased frequency of dust storms, illuminating the strains that luxury fibers can place on fragile ecosystems.

By sourcing keratin from predistributed waste streams such as feathers, wool and cashmere scraps and off-cuts of down bedding, Everbloom is pitching a decoupling of handfeel from herd size. Textile Exchange and others have been pushing brands to develop suites of garments with lower raw-virgin inputs and larger-scale circular feedstocks — here’s a promise to do so while not taking the “tactile qualities” that garner sales out back and shooting them.

Cost Parity and Scale as Systemic Constraints

The company has raised over $8 million from investors including Hoxton Ventures and SOSV to prove that performance and economics can match up.

Instead of asking brands or mills to pay a “green premium,” Everbloom is aiming to hit or beat existing price points. That requires building a supply chain from available waste, minimizing process energy and making sure the fiber fits on today’s high-throughput equipment.

And the drop-in is a promise that matters to fashion houses. Material changes frequently stall not for lack of working lab science, but because the fibers misbehave on looms or dye lines or knitting machines. Everbloom is hoping to sidestep the trust gap that has felled a number of next-gen textiles in recent years by designing toward existing specs and using machinery fashion’s supply chain already knows.

Biodegradability and Verification for Everbloom Fibers

All Everbloom fibers are biodegradable, including content meant for replacing polyester, the brand says. The company is conducting accelerated aging and biodegradation tests to back up those claims, a requirement that brands increasingly make in addition to life-cycle assessments. Separate frameworks like those offered up by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and the Apparel Impact Institute have pushed for verifiable end-of-life pathways, not just lower upstream impact.

If it touts partner brands’ figures, a cashmere-like fiber that degrades at end of life and is sourced from waste could take a bite out of landfill weight and help reduce shedding into the microplastic stream. It could also assist brands in reaching circularity targets without having to sacrifice the soft, warm handfeel that makes sweaters sell.

What Brands Do Now to Evaluate Everbloom’s Claims

Short-term milestones are related to mill trials, colorability, pilling resistance, wash durability and certification.

Brands are looking for alignment with standards like OEKO-TEX and Global Recycled Standard, as well as third-party LCAs to measure impact versus traditional cashmere and polyester.

The bigger question is supply. Given the estimated multi-million-ton annual pool of feathers alone, theoretical potential is high. The execution challenge is turning that waste into consistently soft, spinnable fiber at industrial volumes. Should Everbloom meet its promises, the tag on a future cashmere sweater may recount a strange story: luxury handfeel, engineered from yesterday’s poultry waste.