Two of the most closely watched founders in the new space economy — Even Rogers, of True Anomaly, and Max Haot, of Vast — will share our Space Stage at Disrupt 2025 and we expect sparks to fly.

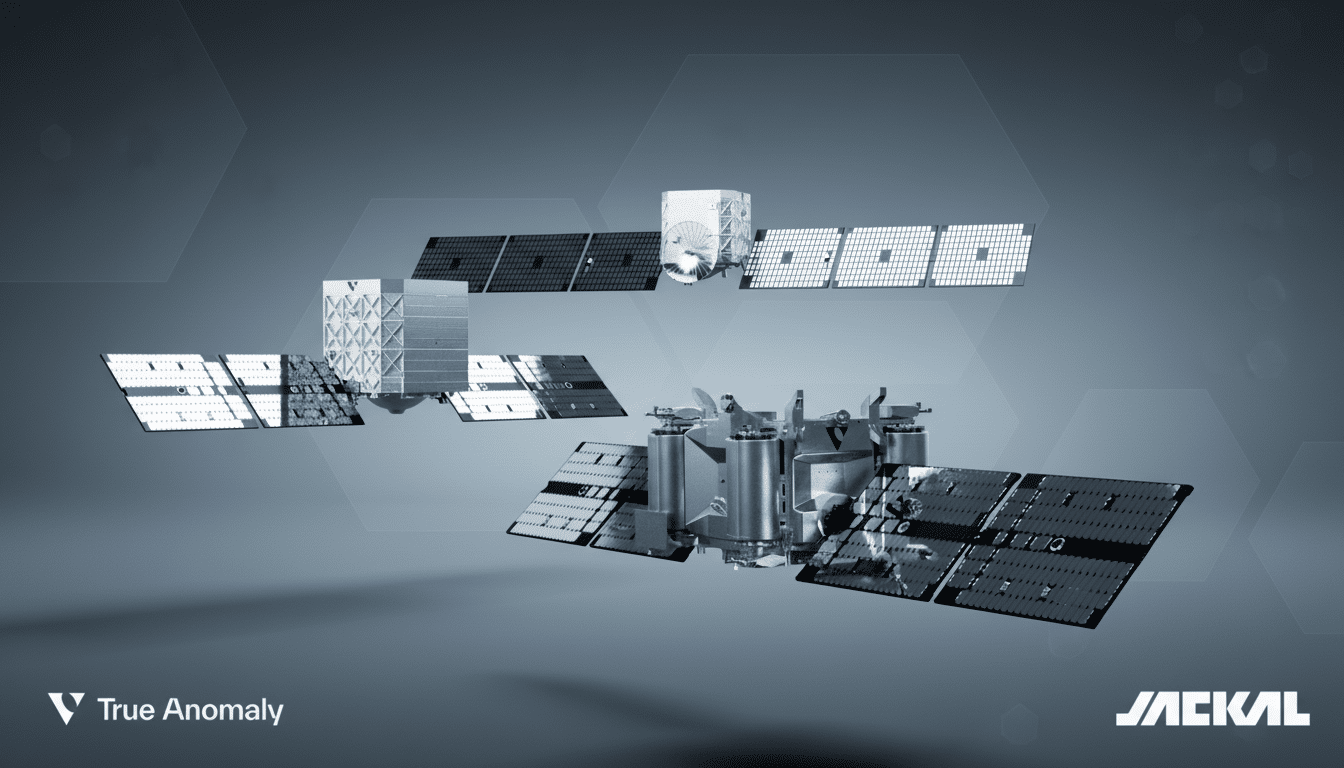

Rogers is also a retired U.S. Air Force officer and DARPA Service Chiefs’ Fellow who now heads True Anomaly, which is developing automated spacecraft and software to safeguard objects in orbit.

Haot, a serial entrepreneur who has sold multiple companies and was the founder of Launcher (which he later sold to Vast) before taking on his current role as CEO of Vast, is racing to prove that commercial space stations — including artificial gravity concepts — can become viable businesses.

Defense-grade tech meets a commercial buildout

Rogers’ own work spans strategy and hardware. He had a hand in writing fundamental doctrine for the U.S. Space Force and is now working on operational tools to make orbit more transparent and predictable. “The thesis that True Anomaly is based on is simple yet urgent: there are thousands of satellites in orbit, with more being launched every week, and satellite operators require accurate rendezvous/proximity operations and space domain awareness to avoid accidents and deter adversarial actions.”

The European Space Agency calculates that more than 36,000 debris objects are tracked in orbit, with hundreds of thousands of smaller flotsam presenting potential collision hazards. That backdrop has prodded governments to tighten up disposal rules and increase monitoring. For startups such as True Anomaly, it’s an opening to deliver dual-use tech that supports both commercial operators and national security customers while advancing norms for how spacecraft move around each other safely.

Vast’s push for artificial gravity space stations

Haot’s journey illustrates how quickly commercial space is growing up. Launcher’s propulsion and orbital transfer vehicle work was subsumed into Vast, which is focused on creating free-flying space stations for crews and research and, eventually, facilities that can exhibit artificial gravity to support longer stints in space. Close-in projects include small stations and human-tended launches, with the long-term vision of making larger spacecraft that can be assembled and serviced in orbit.

This work comes as NASA pivots from the International Space Station to commercial Low Earth Orbit destinations. Government research organizations, such as the NASA inspector general and the U.S. Government Accountability Office, have cautioned that schedules are aggressive and maintaining a continuous U.S. presence in space will rely on aggressive industry implementation. This urgency will favor founders comfortable with hardware iteration, firm-fixed-price contracts and milestone-driven development — a playbook Haot is intimately familiar with.

Why these developments are accelerating in space now

The global space economy, meanwhile, has been growing rapidly, having cleared the half-trillion-dollar threshold and with major banks forecasting a trillion-dollar industry in another two decades or so, according to The Space Report. Satellite production and launch cadence have spiked, driven by proliferated constellations and reusable rockets that have bent cost curves. But safely scaling will require new capabilities: in-space training, formation flying (propelling the approach of several craft), on-orbit servicing and transparent norms for close approaches.

Look for Rogers to advocate for more technical verification in measures that also include policy, like authenticated navigation data, maneuver “keep-out” zones and transparency measures designed to decrease misinterpretation during proximity operations. For his part, Haot will likely focus on how commercial space stations will open up new markets — from microgravity manufacturing to in-space biotech — and why artificial gravity could be the difference-maker for longer-duration human missions and healthier crews.

Public–private momentum and market signals

Policy tailwinds are building. The Federal Communications Commission is pulling back on the regulation of smallsats and tightening up disposal requirements, while the National Space Council is pushing a mission authorization framework for emerging enterprises such as on-orbit servicing. On the defense side, fast acquisition pathways and “as-a-service” buying models are pulling startups into national security programs without years of lead time.

For investors and operators, the convergence of these trends points to a clear way for LEO to finally generate returns: providing security and situational awareness in clogged orbits; logistics services that move and maintain spacecraft on-orbit; and commercial stations that remove barriers to research and tourism. Insurance, data proof and verification services — all-too-often-overlooked parts of the market — could be the connective tissue that de-risks transactions throughout the entire ecosystem.

What to watch on the Disrupt 2025 Space Stage

Attendees should pay attention to how True Anomaly is thinking about real-time decision support in space — not just tracking, but actionable autonomy during close passes — that can be audited by regulators and allies. From Vast, attend for details on station module architecture, human-rating pathways and timelines to artificial gravity demonstrations that transition from renderings to flight-proven hardware.

Together, Rogers and Haot straddle the two-force engine propelling the sector: defense-guided urgency in keeping orbits unfettered, and commercial bravado in building the platforms where new space business would occur. Their session is aiming to provide a no-nonsense take on what it will mean to have both visions make sense — together — at scale.