Boom Supersonic is expanding beyond aviation, raising $300 million to start commercializing a natural gas turbine designed for data centers. The inaugural buyer is Crusoe, which has an agreement to buy 29 units rated for 42 MW each, or a total of 1.21 GW, for $1.25 billion, as it moves quickly to provide its carrying capacity with on-site generation capable of supercharging energy-thirsty AI workloads.

Crusoe Deal Underpins New Power Business

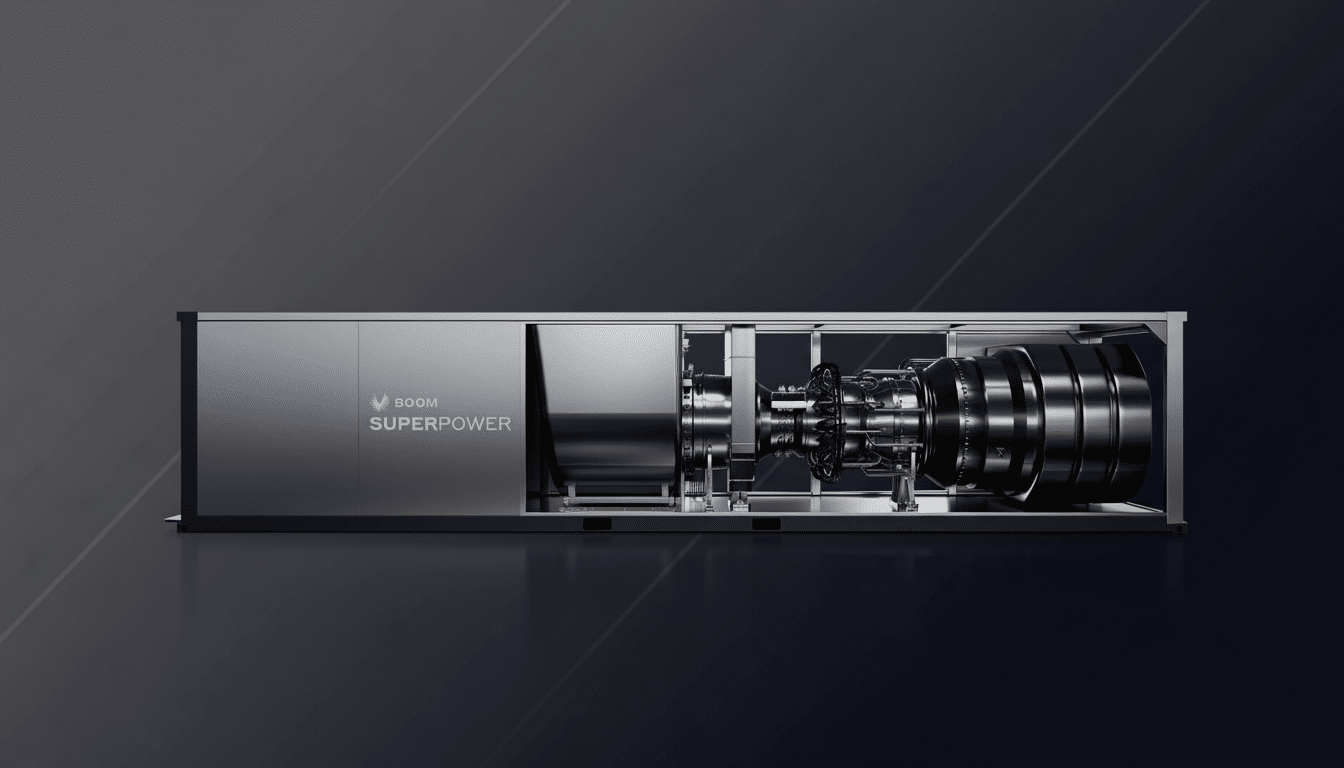

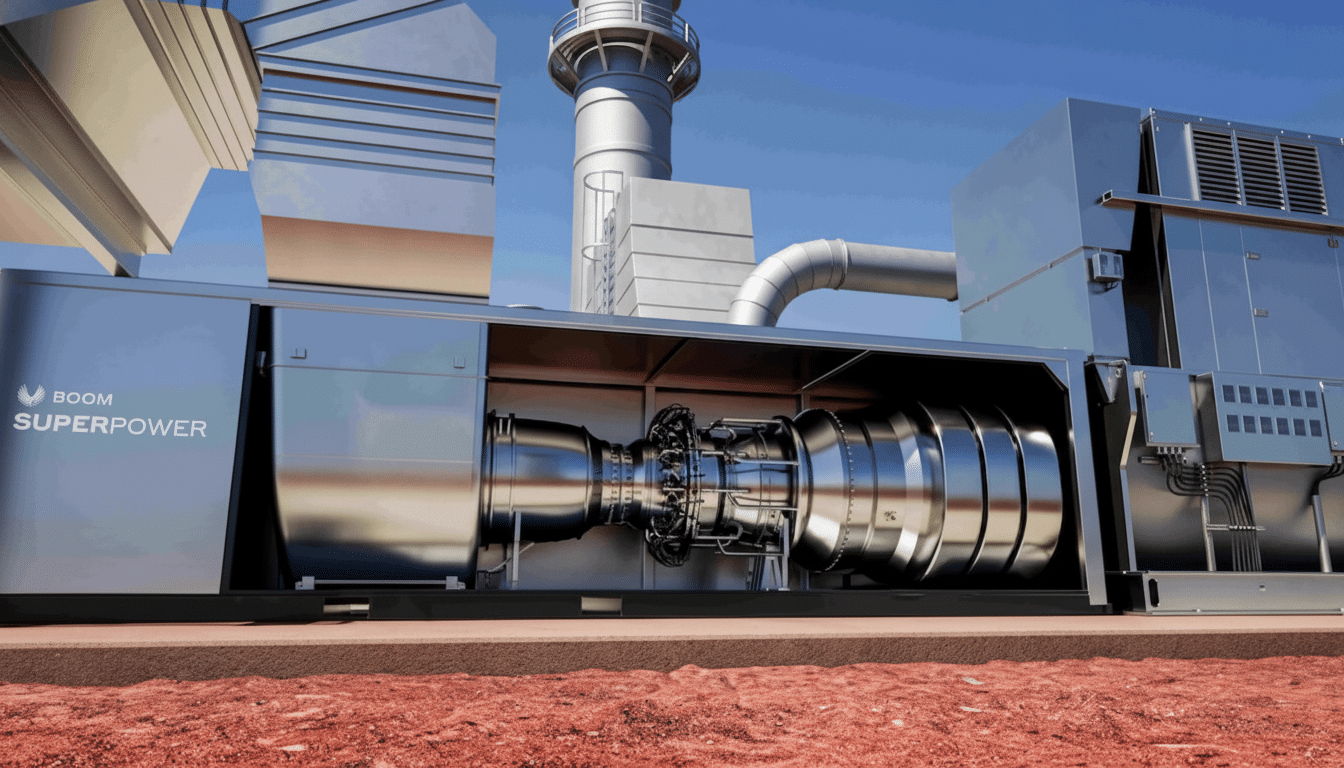

The new stationary device, named Superpower, reconfigures Boom’s aerospace engine architecture for land applications. Crusoe will be paying about $1,033 a kilowatt for equipment that includes the turbines themselves, generators, controls, and preventive maintenance. The rest is up to the buyer — interconnection, emissions equipment, and site build-out — a structure that keeps Boom’s offering modular and quick-deploy.

Deliveries are scheduled to start in 2027, with information on a separate turbine factory to follow. The initial units will be built at existing plants, with production ramping up as part of Boom’s goal to reach 1 GW of capacity in 2028, followed by 2 GW the next year and finally reaching 4 GW in 2030. The round was led by Darsana Capital Partners, as well as investors including Altimeter Capital, Ark Invest, Bessemer Venture Partners, Robinhood Ventures, and Y Combinator.

Boom is running the move as a strategic twin-track: pulling in cash from a near-term commercial product while developing its Symphony engine for next-generation supersonic aircraft.

Superpower and Symphony have about 80 percent of their parts in common, management says, which compresses supply chains and spreads R&D across two markets.

Cost and efficiency in perspective for data center buyers

The Crusoe price point is at the high end just for the turbine component on its lonesome, without accounting for significant balance-of-plant costs. As much as 46 percent of the total installed cost in many power projects can be attributed to the turbine and pollution controls. Divide that by Boom’s figure and the all-in spend may be more than $2,000 per kilowatt — closer to combined-cycle plants planned for the early 2030s than a simple-cycle unit.

Boom states that Superpower aims for 39% thermal efficiency, similar to other aeroderivatives when operating on simple cycle. Efficiencies above 60% are possible if the engine is operated in a combined cycle system where exhausted heat from a secondary power stage is captured for use as additional energy. “Boom sees a field upgrade route to combined cycle; there are already customer kits in the industry that can accomplish this today but upgrades will move projects from fast installs to heavier construction times laid out,” he added.

For data centers, speed-to-power, predictable economics, and location flexibility can justify the premium.

A containerized turbine that shows up largely assembled could be worth more than a cheaper plant that languishes in an interconnection queue for years.

Why data centers would want their own turbines

AI training clusters are jetting power planning into uncharted, God-knows-where territory. Under high-growth scenarios, the International Energy Agency models that data centers, cryptocurrencies, and AI could double total electricity demand from data centers this decade. Meanwhile, interconnection queues are bloating in regions around North America, according to a report from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, with many projects facing several years for completion.

On-site natural-gas turbines offer operators firm capacity; independence of the grid; and compute near users (or cheap land) rather than near-substation headroom. They can not only be built to generate on demand, they present a dispatchable generation profile that pairs nicely with less predictable renewables. Crusoe, which has made money off effectively turning stranded gas into energy and reducing the amount of methane that’s flared in oil production, is an early proponent of modular self-powered data infrastructure (and was a logical first customer for Boom’s approach).

The trade-offs here are noise and air permits. Aeroderivative turbines are not silent; people living near large turbine-backed campuses have experienced audibility out to significant range, emphasizing the necessity for careful siting and sound mitigation. Deployment speed will be just as much a function of emissions controls, fuel sourcing, and local permitting as hardware readiness.

Aerospace DNA and production ambitions at Boom

Superpower’s background, meanwhile, is in aerospace: high power density, rapid ramp rates, and maintenance regimes developed for aviation. The units will be delivered as containerized packages, and developers must provide fuel and electrical connections, and emissions systems. Should Boom achieve its manufacturing goals, it could significantly increase the supply of aeroderivative turbines, a market currently controlled by incumbents who pool demand from aviation and industry cycles.

The company’s testing pedigree gives it credibility. Its XB-1 demonstrator has already proved out crucial supersonic milestones, and the shared parts strategy is meant to enable data center power revenue to sustain long-cycle aerospace development—an echo of how satellite internet has bankrolled space launch vehicle programs.

What to watch next as Boom enters the power market

There will be a good many indicators as to whether Boom’s pivot sticks:

- The pace of factory build-out

- The real-world delivered cost per kilowatt when balance-of-plant is included

- How quickly combined-cycle upgrades materialize

- How much siting, noise, and air permits slow rollouts

For data center operators, the calculus is straightforward — megawatts you can count on, fast. If Boom and Crusoe can bring that about at scale, the line between aerospace and energy could blur in ways that remake both industries.