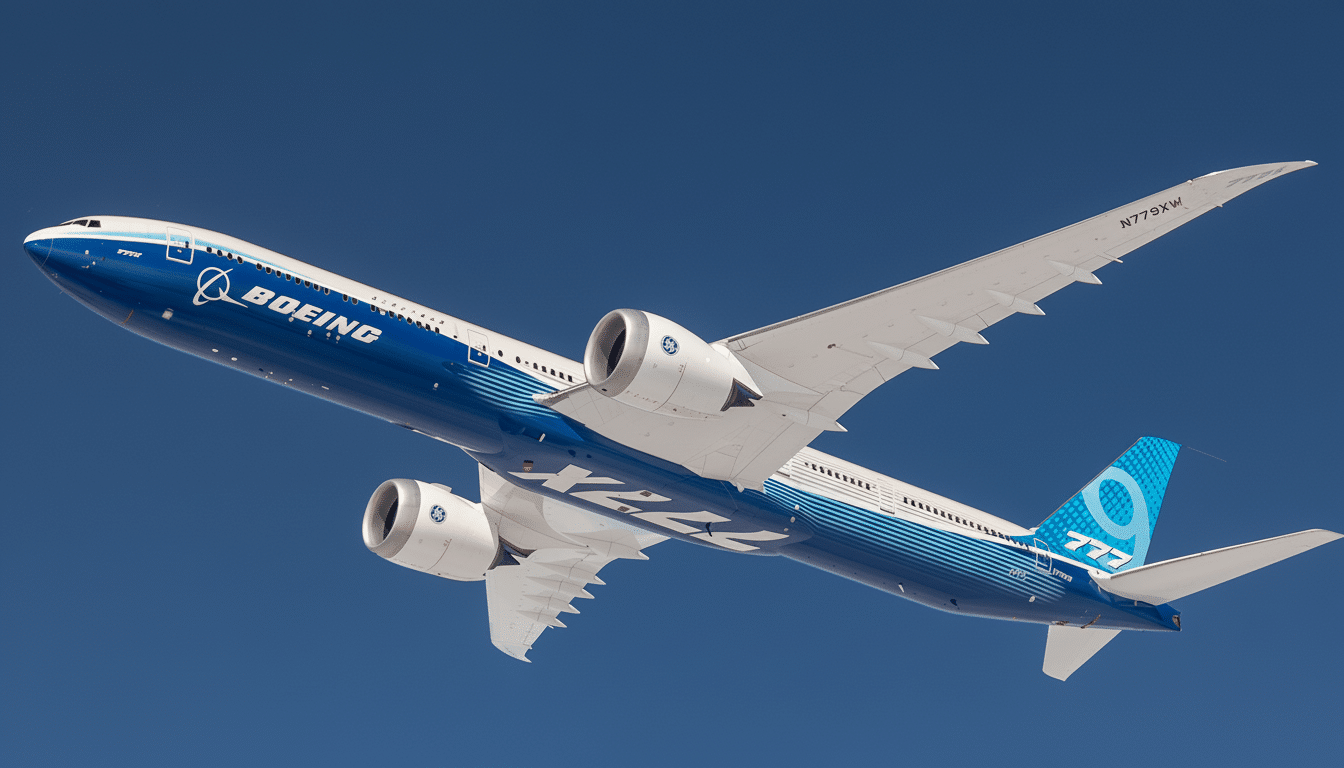

Boeing is taking a frontier approach to tamping down aviation’s indelible climate footprint, inking a sales contract with Charm Industrial that will remove 100,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The move, reported earlier by Axios, highlights how hard-to-abate sectors are moving from efficiency tweaks and sustainable fuels to contracting for durable carbon removal at industrial scale.

Why Boeing Is Buying Carbon Removal Credits Now

Aviation contributes in the range of 2% to 3% of global CO₂ emissions, but its warming effect is greater when taking into account contrails and other non-CO₂ effects, according to research cited by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. And while the aviation industry is finding ways to operate more efficiently, little progress has been made in reducing absolute emissions. Sustainable aviation fuel is still scarce and expensive, accounting for far less than 1 percent of the world’s jet fuel supply, according to figures from the International Energy Agency.

That gap in part has driven companies to such carbon removal contracts to offset nearer-term emissions. One academic analysis estimates that the aviation industry would need to spend a minimum of $60 billion on offsets and removals by 2050 to satisfy net-zero commitments. Boeing’s new deal could amount to growing interest in approaches such as the Charm deal that offer more durability and verification than traditional offsets.

How Bio-Oil’s Carbon Removal Pathway at Charm Works

Charm Industrial vacuum-cleans agricultural and forestry residues, materials like corn stover and slash that would otherwise rot or be burned, and turns them into a thick, inky “bio-oil” through a process called pyrolysis. Instead of processing that oil into fuel, Charm pumps it deep underground and channels it through buried geologic formations — depleted oil wells chief among them — in which the company says the carbon will remain locked away for centuries.

The company then sells carbon removal credits backed with third-party verification. A carbon removal registry called Isometric has been reviewing early projects, and Charm has emphasized measurement, reporting, and verification. The idea is to sidestep some of the permanence and leakage problems that have plagued traditional land-based offsets by trapping carbon underground in a chemically stable form.

Current Costs and the Scale Challenge for Removal

Durable removal is still expensive. Two years ago, another group led by Frontier and including Stripe, Alphabet, and Microsoft purchased 112,000 tons from Charm for $53 million, or roughly $470 a ton. Charm says that its ultimate goal is closer to $50 per ton, a price point at which removals could become much more accessible for industrial buyers — though major strides will still have to be made in logistics, efficiencies within the process, and deployment scale.

For perspective, commercial aviation produced on the order of 900 million metric tons of CO₂ in the year prior to the pandemic, according to the International Air Transport Association. Boeing’s 100,000-ton deal offers significance to the carbon removal market while also being obviously a fraction of industry-wide emissions. It’s the gamble that early demand can move a cost curve like the one we’ve seen with solar and batteries — learning-by-doing, better supply chains for biomass residues, more standardized injection permits, and improved reactor designs.

Permanence and Supply Risks in Question

Bio-oil sequestration stands or falls with its permanence and life-cycle accounting. Independent analysts such as CarbonPlan have advised buyers to closely examine the sourcing of biomass feedstocks, transportation emissions, and site-level monitoring to keep net removals robust. Regulators are also important: in the United States, injection wells come under EPA’s UIC program, and stability of oversight is a concern for achieving long-term permanence.

And in some forms, Charm also produces biochar, a carbon-rich solid that can help promote soil health when spread on fields. Promising though it may be, the degree to which certain types of biochar are permanent also depends on the kind of soil and climate, as well as how specific forms of it are used, and the market standards for all this stuff are still evolving. What’s attractive to Boeing, at least, seems to be the geologic route that Charm is taking — one aimed at 100% solid sequestration with more robust MRV.

What This Means for Aviation Decarbonization

Boeing’s acquisition doesn’t obviate the potential for cleaner aircraft and fuels — both are critical long-term to decarbonization. But it represents an unwelcome admission: despite substantial efficiency savings and expansion of SAF, aviation will bear leftover emissions for decades. Durable removals are one of the only levers we have to offset that remainder.

The deal will also accelerate a wider corporate reshuffling. People in tech and finance have already made the first bets that will grow to become the market for removal via programs such as Frontier’s advance market commitments. And, as manufacturers and airlines rush in, they bring with them steady offtake and sector-specific demands that can shape the next wave of projects — more transparency on durability, clearer alignment with standards such as the Science Based Targets initiative, and procurement practices that reward auditable climate impact over lowest sticker price.

If early adopters like Boeing indirectly help drive costs down and verification up, removal pathways like bio-oil injection might transition from pilot-scale novelty into a practical tool in aviation’s climate toolbox. The stakes are high: this is a sector that needs solutions that can scale without hand-waving. This contract is a sign the industry knows it — and that it’s willing to pay for carbon that remains buried.