An extensive outage at Amazon Web Services that began on Tuesday disrupted vast stretches of the internet, including platforms for everything from payments and media to customer service and data monitoring. Since so many apps are built on top of AWS behind the scenes, a single regional incident led to issues for millions and millions of users.

Initial reports on the AWS Health Dashboard suggested problems were concentrated in the US-EAST-1 region, home to Amazon’s largest and most trafficked data center hub. The network issues were communicated by engineers along with another incident that was related to DNS, preventing access to critical services.

What failed and where outages impacted AWS services in US-EAST-1

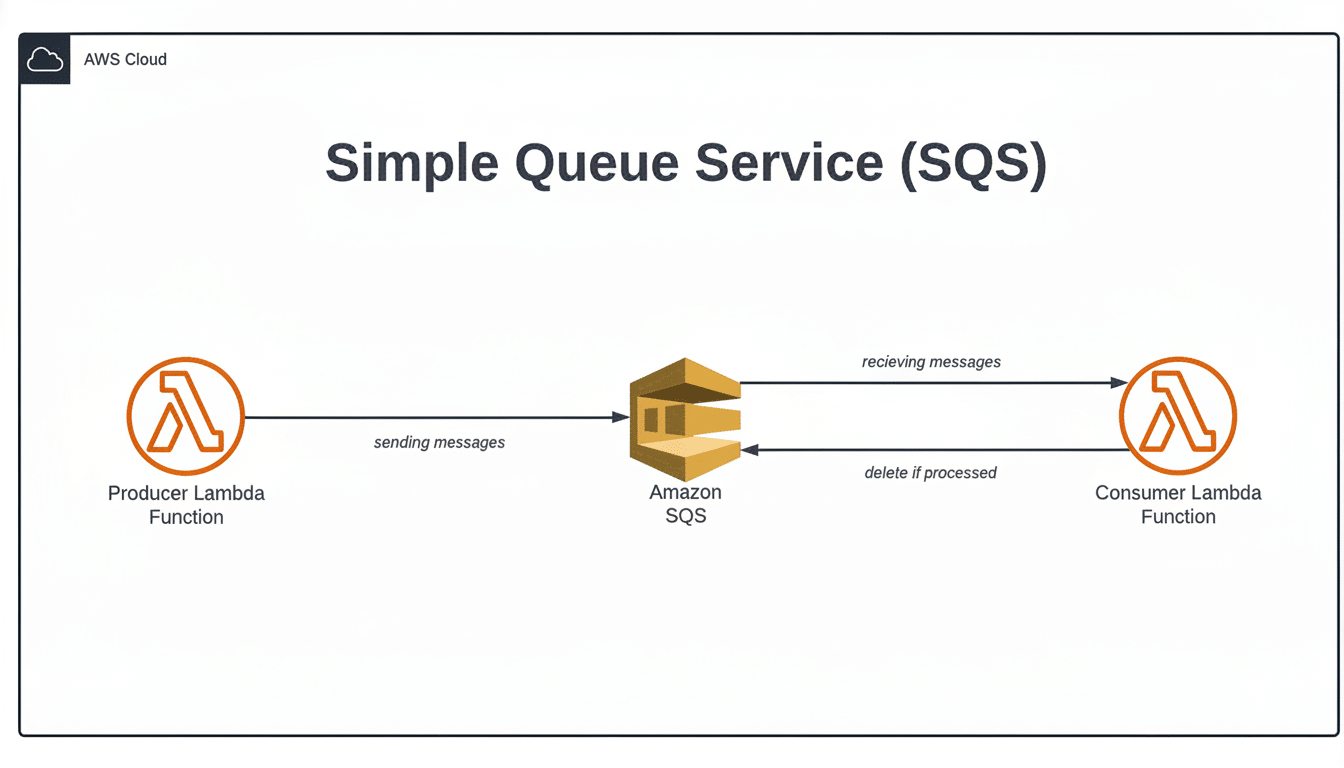

AWS acknowledged that service disruptions occurred across many offerings in US-EAST-1, including DynamoDB, Simple Queue Service (SQS), and Amazon Connect. Put simply, apps that were having trouble reading and writing data, processing background jobs, or taking care of contact-center calls would start to slow down or crash.

Adding to the confusion, AWS also mentioned a DNS-based disruption. DNS is the phone book of the internet: it turns familiar network names into actual numbers that applications request. When DNS fails, healthy databases and APIs can even disappear from sight to the apps that rely on them.

As mitigation started to be implemented, AWS saw the platform recover and preemptively throttled some of its traffic to restore stability. That kind of step is typical for a large-scale event; it prevents a surge of traffic that carries over from a wave of retries and causes an encore failure.

Why AWS DNS issues cascaded to disrupt much of the internet

Many services in AWS are accessed via named endpoints that utilize internal and external DNS resolvers. If resolvers are either degraded or misrouted, clients will receive timeouts rather than clean errors. Microservices then begin retrying, queues start to backfill, and autoscaling is triggered — frequently compounding the initial failure.

In cases like this, the data is not generally lost; it’s stuck. For instance—apps using DynamoDB may have been experiencing perfectly good tables, but the issue at play was one of architecture and service discovery—DNS is required to locate the endpoints for services. The result resembles missing data, but it is, in fact, a transient loss of directions.

Who was affected and what users experienced during outages

Tracker reports by users of those same brands on Downdetector surged. People reported issues with logging in, account verification delays, and stalled checkouts, as well as chat or streaming disruptions. The pattern was inconsistent: some features inside the same app worked, while others spun forever or returned error messages.

Operating teams were seeing elevated 5xx error rates and high latency in dependent services. In telecom and payments, even small latent islands of packet loss or DNS latency can set off a chain reaction of failed authentications and timed-out fraud checks that make it feel like the world is nuked for end users.

What AWS said about the incident and current recovery status

AWS said the DNS problems were resolved and US-EAST-1 connectivity was showing some recovery, even as root-cause analysis remained in progress. It also noted new network connectivity symptoms throughout the day, a sign that once large platforms have braked to adjust capacity, they can suffer from aftershocks.

Customers may continue to see localized throttling or elevated latencies as the environment normalizes. That includes delayed queue processing in SQS, intermittent read/write errors for DynamoDB clients, and partial restoration of Amazon Connect contact flows while backlogs clear.

Cybersecurity analysts, including researchers at Sophos, noted the characteristics align more with an internal networking or resolution fault than a coordinated attack. Media outlets such as CNN and The Guardian reported similar assessments from academic and industry experts, consistent with AWS’s own messaging.

US-EAST-1 is AWS’s busiest region, the default destination for many new workloads and a central point for numerous control-plane operations. That concentration can increase the blast radius of a misconfiguration or capacity shortfall, even when individual services are architected for high availability.

The stakes are high. Synergy Research Group estimates AWS accounts for roughly a third of global cloud infrastructure spend, ahead of Microsoft and Google. When a core AWS region wobbles, the impact is macroeconomic: logistics, media, healthcare, finance, and public services can all feel the shock.

Digital rights groups, including Article 19, have warned that excessive dependence on a handful of hyperscalers poses systemic and societal risks. Their argument is not anti-cloud; it is pro-resilience—more diversity in providers and architectures reduces the chance that one fault knocks out essential services.

Practical steps teams can take for resilience

Practical steps include:

- Multi-Region architectures with active-active failover

- Decoupled DNS resolvers and health checks

- Strict retry budgets and circuit breakers to avoid stampedes

- Validate Route 53 and VPC resolver behavior under stress

- Rehearse failover using game days or chaos testing

For customer-facing apps, graceful degradation matters:

- Cache critical reads

- Queue writes for later

- Communicate status clearly

The goal is not perfect uptime—no provider can promise that—but predictable, bounded failure modes that keep core functions available when a major region stumbles.

What to watch next

Expect AWS to publish a post-incident summary detailing triggers, mitigations, and long-term fixes.

Key areas to look for include:

- DNS capacity and failover design

- Network path diversity inside US-EAST-1

- Safeguards to prevent retry storms

For now, services are stabilizing, but the lessons will outlast the outage.